Portuguese literature: between minor status and transcontinental awareness

Portuguese literature, since its medieval beginnings, although minor in size and, at different times, lacking the so-called "great works", makes nonetheless one of the most consistent literary histories in Europe in terms of unity and continuity. This is the aspect that appeals to the literary historian in me; on many occasions, I have looked at Portuguese literature as a flux of imagery, ideas, genres, and forms. I have paid special attention to the continuity of millenarian myths, such as Sebastianism and the Fifth Empire, connecting my two primary areas of specialization, which are early modernity and the modern and contemporary period. Certainly, Portuguese Romanticism started not only with Garrett's Camões but also with the deconstruction of Sebastianist myth in Frei Luis de Sousa. Later, the same imagery, deeply rooted in cultural history, reappeared even on such occasions as the colonial war (if we consider such books as Manuel Alegre's Jornada de África). I have been a very keen researcher of such continuities.

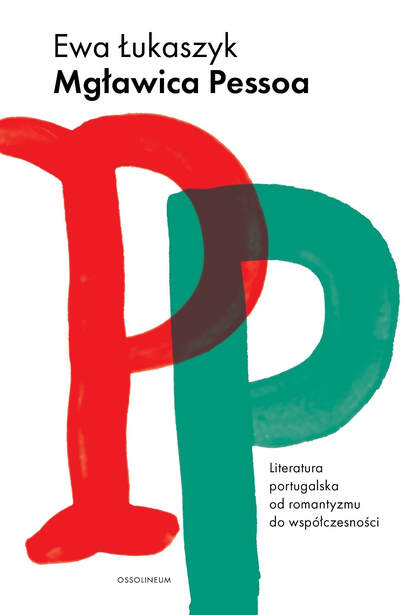

Overall, Portuguese studies have been my primary academic specialization since my studies in Romance Philology at the Maria Curie-Sklodowska University in Lublin as well as my various scholarships (TEMPUS, Instituto Camões, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation) at the University of Lisbon all along the 1990s. I earned my PhD (1999) and habilitation (2003) working on Portuguese literature and cultural history, and the "major achievement" leading to my official full professor title in 2018 was defined as "thorough analysis of the literary work of José Saramago." In Polish academic context, I was the "number one" academic author writing on Portugal. I have published several books on the history of Portuguese literature and culture: Wspolczesna proza portugalska (2000), Terytorium a swiat (2003), Pokusa pustyni (2005), Imperium i nostalgia (2015), Mglawica Pessoa (2019), as well as over a hundred research papers in this area, without counting language manuals, various translations from Portuguese and other works related to Lusophone culture.

Overall, this is a major body of academic texts that arguably makes me the most advanced Lusitanist scholar in Poland, standing comparison not only with contemporary colleagues, but also with the historical precedent established by Janina Z. Klave, a professor of the University of Warsaw who launched the foundations of Portuguese and Lusophone studies in Poland along the decades 1970s - 1980s. I am proud to say that, as a literary historian, I gave continuity to the work of Janina Z. Klave, including her major book, Historia literatury portugalskiej. Zarys, published in 1985. I have also extensively worked on José Saramago, to whom I dedicated the monograph Pokusa pustyni in 2005. Less assiduously, I have written on Fernando Pessoa, publishing several studies as well as introductions to volumes of his poetry in Polish translation. I have published on Vergílio Ferreira, Sophia de Mello Breyner, Jorge de Sena, Teolinda Gersão. Gonçalo M. Tavares, and others. In recent years, my approach to Portuguese texts has been mostly comparative, inscribing them in a larger literary and intellectual history. Such an approach may be noticed in my recent books, Imperium i nostalgia as well as Mglawica Pessoa, which serves the target of bringing Portuguese literature closer to Polish references, sensibility, and mental horizon. The latter book has been written with the support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation which permitted me to spend the academic year 2016/2017 perfecting this publication narrating the history of Portuguese literature from Romanticism to the newest authors.

After the publication of Mglawica Pessoa, I stopped writing in Polish and focused on my long-overdue international career. Having closed the cycle of projects related to contemporary Portuguese literature together with my Polish period, I am currently rediscovering early-modern Portuguese literature in its global inscription. Early-modern mater played a crucial role in my habilitation book, Terytorium a swiat, and later on, in Imperium i nostalgia. In 2017-2018, I considerably developed my competencies in both philology and history of ideas as I spent my Marie-Curie fellowship at the Institute of Renaissance Studies in Tours, where I worked on the idea of recovering Adamic language in the aftermath of maritime discoveries. At the present moment, I work on Adamic restitution as an element of utopian thought of early modernity and a factor fostering the birth of transcontinental awareness. I am interested in studying Portuguese expansion focusing on the zones of contact and interpenetration of intellectual spheres and imageries, Christianity, and Islam.

Overall, Portuguese studies have been my primary academic specialization since my studies in Romance Philology at the Maria Curie-Sklodowska University in Lublin as well as my various scholarships (TEMPUS, Instituto Camões, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation) at the University of Lisbon all along the 1990s. I earned my PhD (1999) and habilitation (2003) working on Portuguese literature and cultural history, and the "major achievement" leading to my official full professor title in 2018 was defined as "thorough analysis of the literary work of José Saramago." In Polish academic context, I was the "number one" academic author writing on Portugal. I have published several books on the history of Portuguese literature and culture: Wspolczesna proza portugalska (2000), Terytorium a swiat (2003), Pokusa pustyni (2005), Imperium i nostalgia (2015), Mglawica Pessoa (2019), as well as over a hundred research papers in this area, without counting language manuals, various translations from Portuguese and other works related to Lusophone culture.

Overall, this is a major body of academic texts that arguably makes me the most advanced Lusitanist scholar in Poland, standing comparison not only with contemporary colleagues, but also with the historical precedent established by Janina Z. Klave, a professor of the University of Warsaw who launched the foundations of Portuguese and Lusophone studies in Poland along the decades 1970s - 1980s. I am proud to say that, as a literary historian, I gave continuity to the work of Janina Z. Klave, including her major book, Historia literatury portugalskiej. Zarys, published in 1985. I have also extensively worked on José Saramago, to whom I dedicated the monograph Pokusa pustyni in 2005. Less assiduously, I have written on Fernando Pessoa, publishing several studies as well as introductions to volumes of his poetry in Polish translation. I have published on Vergílio Ferreira, Sophia de Mello Breyner, Jorge de Sena, Teolinda Gersão. Gonçalo M. Tavares, and others. In recent years, my approach to Portuguese texts has been mostly comparative, inscribing them in a larger literary and intellectual history. Such an approach may be noticed in my recent books, Imperium i nostalgia as well as Mglawica Pessoa, which serves the target of bringing Portuguese literature closer to Polish references, sensibility, and mental horizon. The latter book has been written with the support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation which permitted me to spend the academic year 2016/2017 perfecting this publication narrating the history of Portuguese literature from Romanticism to the newest authors.

After the publication of Mglawica Pessoa, I stopped writing in Polish and focused on my long-overdue international career. Having closed the cycle of projects related to contemporary Portuguese literature together with my Polish period, I am currently rediscovering early-modern Portuguese literature in its global inscription. Early-modern mater played a crucial role in my habilitation book, Terytorium a swiat, and later on, in Imperium i nostalgia. In 2017-2018, I considerably developed my competencies in both philology and history of ideas as I spent my Marie-Curie fellowship at the Institute of Renaissance Studies in Tours, where I worked on the idea of recovering Adamic language in the aftermath of maritime discoveries. At the present moment, I work on Adamic restitution as an element of utopian thought of early modernity and a factor fostering the birth of transcontinental awareness. I am interested in studying Portuguese expansion focusing on the zones of contact and interpenetration of intellectual spheres and imageries, Christianity, and Islam.

ongoing research & events

My first lecture in Portuguese in 17 years (sic!). That's a big event, the opening of the Centro Paulina Chiziane at the University of Warsaw. A good moment to speak about the passage between the bashful self-definition of the Portuguese culture as "a filha ilegítima da cultura universal" (Eduardo Lourenço) and the blossoming of its self-aware worlding. And of course, few things are as prone to get worlded as Portuguese studies. Especially, because of that long-lived awareness of being marginal, peripheral, minor.

My narration recapitulates the evolution going roughly from the 1960s, glosing on Jorge de Sena's Metamorfoses as an attempt at worlding the Portuguese culture that stood up as an alternative to the Salazarian conception of the "Portuguese world". In the fire of the polemics between José Régio and Eduardo Lourenço, all the discomfort of feeling minor and excluded from the circle of "great" European literatures comes to the fore. What could be done about it? There are solutions. One of them is precisely the attitude of glorious self-isolation in the little "world" made up by Portugal and her colonies. The project of Lusophony formalised in the 1990s, can be situated in the same line. Another solution is the confrontation with the "great" world of "major" literatures. The inclusion of the chapter on Fernando Pessoa in Harold Bloom's Western Canon might be seen as the recognition that the generation of Régio and Lourenço was striving for. Yet the canon, and much less the Western canon, was not to last. The new millennium brought the wave of hybrid, transcultural, plural, and transgressive literatures. The Portuguese culture so centred on its self-definition and identity problems, was once again ill-prepared to face the change of the tide. Nonetheless, there is a transcolonial dimension to be found - perhaps quite surprisingly, in José Saramago's late novel, Caim. I read it as a closure of the early-modern, Adamic period in which the idea of a unique, unified humanity was the starting and final point. Caim deconstructs the biblical narration of unique creation, making Adam just one among mankind's forefathers. As a consequence, the first men, and the first Portuguese, leave their paradise not as entitled conquerors and settlers of the world, but as the first refugees. They don't occupy the earth, they are mere nomads. This is, after all, a very pertinent definition of the Portuguese historical destiny. As yet another poet, Manuel Alegre, has said: Porque o mar tiveste / Nada tiveste. The Portuguese empire, at least as the Estado da Índia, was a chimera. And Alegre, the combatant of the colonial war, did not mean just India... Finally, when the early-modern chimeras are exorcised, Portuguese literature is ready for a new worlding, quite different from the old concept of Mundanus ready to inhabit the totality of the earth in one of Padre Vieira's sermons.

My narration recapitulates the evolution going roughly from the 1960s, glosing on Jorge de Sena's Metamorfoses as an attempt at worlding the Portuguese culture that stood up as an alternative to the Salazarian conception of the "Portuguese world". In the fire of the polemics between José Régio and Eduardo Lourenço, all the discomfort of feeling minor and excluded from the circle of "great" European literatures comes to the fore. What could be done about it? There are solutions. One of them is precisely the attitude of glorious self-isolation in the little "world" made up by Portugal and her colonies. The project of Lusophony formalised in the 1990s, can be situated in the same line. Another solution is the confrontation with the "great" world of "major" literatures. The inclusion of the chapter on Fernando Pessoa in Harold Bloom's Western Canon might be seen as the recognition that the generation of Régio and Lourenço was striving for. Yet the canon, and much less the Western canon, was not to last. The new millennium brought the wave of hybrid, transcultural, plural, and transgressive literatures. The Portuguese culture so centred on its self-definition and identity problems, was once again ill-prepared to face the change of the tide. Nonetheless, there is a transcolonial dimension to be found - perhaps quite surprisingly, in José Saramago's late novel, Caim. I read it as a closure of the early-modern, Adamic period in which the idea of a unique, unified humanity was the starting and final point. Caim deconstructs the biblical narration of unique creation, making Adam just one among mankind's forefathers. As a consequence, the first men, and the first Portuguese, leave their paradise not as entitled conquerors and settlers of the world, but as the first refugees. They don't occupy the earth, they are mere nomads. This is, after all, a very pertinent definition of the Portuguese historical destiny. As yet another poet, Manuel Alegre, has said: Porque o mar tiveste / Nada tiveste. The Portuguese empire, at least as the Estado da Índia, was a chimera. And Alegre, the combatant of the colonial war, did not mean just India... Finally, when the early-modern chimeras are exorcised, Portuguese literature is ready for a new worlding, quite different from the old concept of Mundanus ready to inhabit the totality of the earth in one of Padre Vieira's sermons.

selected monographs, papers & chapters

Empire in decay. 'Visionary blindness' and trauma of the colonial war in Portuguese literature

[in progress]

The article presents texts thematising the colonial war waged by the Portuguese in Angola and Mozambique in the 1960s and early 1970s. The focus is on the persistence of Sebastianism and other national myths as the prism to the literary treatment of the traumatic events in such novels as Lugar de massacre and Jornada de Africa. The hypothesis explored is that the literary expression of the colonial war fostered strong internalization of the conflict and the traditional 'visionary blindness' referred to Portuguese national mythology should be associated with a peculiar unability to perceive African reality and in particular, the adversary and his or her reasons. On the other hand, a literary exploration of such topics as madness and overt presentation of post-war trauma as a psychiatric problem contributed to a profound re-evaluation of colonial history and helped the Portuguese to close this chapter.

Romantism on the far ends of Europe:

Portugal, Poland and the Christ of nations

|

„Romantyzm krańców Europy. Portugalia, Polska i Chrystus narodów”, Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis. Studia Historicolitteraria, no 21/2021, p. 87-99. ISSN: 2081-1853 e-ISSN: 2300-5831

https://studiahistoricolitteraria.up.krakow.pl/article/view/8913/8063 The article is a tentative of providing a comparative outlook of Polish and Portuguese Romanticism. Taking for the starting point the famous parallel between the opposite ends of Europe sketched by the 19th c. historian Joachim Lelewel, the author claims that Polish and Portuguese literature, although having almost no direct contacts with each other, participated in the same system of cultural coordinates established by European Romanticism. At the same time, both nations had some sort of dispute or clash with Europe, developing syndromes of inferiority, as well as megalomaniac visions of their moral superiority. Almeida Garrett and Alexandre Herculano tried to provide a solution, harmonizing their country with its European context. The conclusion accentuates the uttermost victory of this harmonizing vision, presenting the contemporary Portuguese culture as fully Europeanized and contrasting it with the doubts concerning European identity that may be observed in the contemporary Poland. |

A tradição épica na hora da “lusofonia horizontal”.

Uma viagem à Índia de Gonçalo M. Tavares face a outras vozes poéticas da língua portuguesa

|

Scripta, vol. 24, no 52/2020, p. 119-138. ISSN 1516-4039; e-ISSN 2358-3428

http://periodicos.pucminas.br/index.php/scripta/article/view/23984/17588 The article is a contribution to the study of the evolution of Lusophony, from its political formation in the last decade of the 20th century till the new reality observed by José Eduardo Agualusa. The first formulation implied, according to Alfredo Margarido, a return to the period of Maritime Discoveries; such a return effectively happened, on the symbolic level, with the ironic re-elaboration of the literary model given by Camões in Uma viagem à Índia by Gonçalo M. Tavares. The alleged “horizontal” dimension of the new Lusophony is debated through the confrontation of Tavares with the epic resonances of other poetical voices: Tony Tcheka, Conceição Lima, Filinto Elísio and Afonso Cruz. Following the theory of minor literature formulated by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, the author speaks of a “desertification” of the epic tradition that loses its glorious connotations. As a consequence of this process, the closed horizon of hegemonic literature opens up for new connectivities.

| |||||||

nebula pessoa

Summary

The book is an extensive presentation of the Portuguese literary history, going from 1826 to 2017. The content is divided into eight "lectures" and eight "interludes". While the former offer a synthetic narration involving currents and their major figures, the latter focus on some chosen aspects of the Portuguese culture, offering a personal appreciation and insight in such key matters as love, travel, translatability of the term saudade, the Portuguese relations with Europe and Africa, modernity, literary success and illustrated books.

Mgławica Pessoa. Literatura portugalska od romantyzmu do współczesności, Wrocław, Ossolineum, 2019, 470 pp.

ISBN 978-83-66267-04-6

Po cóż więc czytać to wszystko, po cóż interesować się literaturą kraju ogarniętego przeczuciem własnego kresu? Czy po to, żeby pełniej odczuć to, że sami, póki co, istniejemy? Literatura portugalska, zwłaszcza widziana w taki sposób, jak próbowałam to zrobić w tej książce, jako organiczna całość, a nie oglądana przez pryzmat dzieł indywidualnych pisarzy, dostarcza tej szczególnej mądrości, jaką Edward Said próbował zawrzeć w pojęciu „stylu późnego”. To końcowa lekcja wyczytana z długiego trwania, które w ostatecznym rachunku nie przynosi akumulacji bogactwa, lecz przeciwnie, ruinę. Zwykle liczymy na to, że tradycja kulturowa przyniesie wartościowe dziedzictwo, że mijający czas pozostawi coś po sobie, choćby książki. Historia literatury portugalskiej ukazuje coś przeciwnego: niebezpieczeństwo repetycji, kolistość paradygmatu prowadzącą do końcowego wyczerpania. Obfituje w obrazy apokalipsy, która pochłania również własną historię, w teksty, które na koniec pożerają same siebie, tak jak zrośnięci końcami palców bliźniacy, by sięgnąć raz jeszcze do powieści Peixoto, zjadający własny obraz w formie wyszukanego dania przygotowanego przez kucharkę. A na koniec trzeba jeszcze spożyć wielkie spiralne serce z najdroższej wołowiny, które okazuje się zatrute grzybami, gdyż miłość w Portugalii może się spełnić tylko tak, jak miłość Pedra i Inês, jako pocałunek złożony na dłoni trupa.

Chyba żadna z literatur europejskich nie niesie porównywalnego ładunku turpizmu i nekrofilii. Ta powtarzana w nieskończoność ostatnia lekcja goryczy mówi jednak coś istotnego o człowieczeństwie, rysującym się jako ułomne z natury, pozbawione pełni, której na próżno szukał bohater Virgília Ferreiry. Apokalipsa pochłania teksty, nie pozwala ostać się ludzkiej historii, przynosi jednak moment złamania pieczęci, ostatniego objawienia. Tą ostatnią, odkrytą na koniec prawdą okazuje się pustka, próchno, rozpad pozbawiony transcendencji. Otwierają się wrota pustyni, na którą musiał wyjść całkowicie człowieczy Jezus z powieści Saramago, by napotkać tam bezlitosne, pozbawione miłosierdzia bóstwo. W 2005 roku, pisząc książkę o tym pisarzu, Pokusę pustyni, próbowałam się cofnąć przed narzucającą się konkluzją. Wydawało mi się, że nie może przecież o to chodzić. A jednak wydane później powieści Saramago, przede wszystkim Kain, upewniły mnie co do nieuchronności najbardziej radykalnej lektury. Chodzi właśnie o ostateczną likwidację, po której nie ma nawet mowy o korzystnej wyprzedaży, na jaką liczył Kalaf Epalanga.

Przekreśla to możliwość translatio imperii. Milenarystyczny projekt historii, jaki głosił niegdyś barokowy kaznodzieja António Vieira i jaki miał się zrealizować za sprawą Portugalczyków w postaci powszechnego imperium pokoju, został przekształcony w całkiem odmienną eschatologię absolutnego końca czasów, apologię pustki nastającej po ostatnim imperium, które doszło własnego kresu i wygasło bezpotomnie. Paradoksalnie jest to finałowy akord megalomanii Portugalczyków i ich przeświadczenia o własnej znikomości, spełnienie podwójnego kompleksu wyższości i niższości, tej narastającej oscylacji, dążącej jednocześnie do nieskończoności i do zera. Tym, co pozostaje, jest, jak sądzę, pochwała średniej drogi, pracowitej zaradności północnej Europy, materialnej skrzętności, na którą Portugalczycy nigdy nie zdołali się zdobyć, i miłości za życia, która zaświadcza o sobie przez codzienną troskę.

Reviews of this book:

Eliasz Chmiel, ”Ewa Łukaszyk, Mgławica Pessoa. Literatura portugalska od romantyzmu do współczesności”, Estudios Hispánicos, no 28, 2021, p. 156-159.

Renata Diaz-Szmidt, „Literatury portugalskiej zmagania z pustką”, Nowe Książki, no 2, 2020.

Sabina Strózik, „Archipelagi spadających gwiazd”, ArtPapier, no 19(379)/2019.

Alberto Caeiro, or life before philosophy

“Alberto Caeiro, czyli życie przed filozofią”, Fernando Pessoa, Poezje zebrane. Alberto Caeiro, trans. Gabriel Borowski, Kraków, Lokator, 2020. (Foreword). |

Ricardo Reis and the oxymoron of the avant-garde

“Ricardo Reis i oksymorony awangardy”, Fernando Pessoa, Poezje zebrane. Ricardo Reis, trans. Wojciech Charchalis, Kraków, Lokator, 2019, p. 5-19. ISBN 978-83-63056-62-9. (Foreword). |

Raczynski in Portugal. The legacy of a cultural clash

|

“Raczyński w Portugalii. Spuścizna 'zderzenia kultur'”, Postscriptum Polonistyczne, no 1 (21)/2018, p. 27-43. ISSN 1898-1593;

doi:10.31261/PS_P.2018.21.02 http://www.postscriptum.us.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/2-%C5%81ukaszyk.pdf The article presents Atanazy Raczyński’s research on Portuguese art against the background of the modernisation and Europeanisation processes going on in Portugal in the 19th century. His specific view of Portuguese artistic heritage and openly expressed critical opinions made of him a controversial figure, which paradoxically contributed to the importance and resonance of his work. Discouraged by the conflict with his Portuguese milieu, Raczyński did not complete his final synthesis. Nevertheless, his letters to the Art Society in Berlin and his dictionary of Portuguese artists initiated history of art (in the proper sense of a scientific discipline) in Portugal.

| |||||||

From the maritime empire to reconquered earth. Essay on the 'Portuguese world'

“Od morskiego imperium do ziemi odzyskanej. Esej o 'świecie portugalskim'”,

Kultura – Historia – Globalizacja, no 21/2017, p. 149-160. ISSN 1898-7265

http://www.khg.uni.wroc.pl/files/11%20KHG_21%20Lukaszyk%20t.pdf

Reprinted in volume: Historia – Kultura – Globalizacja, vol. VIII, Adam Nobis, Piotr Badyna, Piotr J. Fereński (eds.), Wrocław, Arboretum, 2018, p. 653-666. ISBN 978-83-62563-68-5

The essay comments on the evolution of the Portuguese concept of identity between its medieval and early-modern origins and the decline of the colonial empire. The concept of the “Portuguese world”, exemplified in the exposition organised in 1940, is treated as a simulacrum covering the deficiencies of the colonial project. At the same time, the vindication of the “earth” as opposed to the maritime space of the supposed “paracletic” destiny of the nation, is brought back to the Salazarian epoch with the figure of Henrique Galvão. Portugal is imagined as a garden, in which also the Other is included, as it can still be seen in the collection of "peoples of the empire" decorating the botanical garden in Belem. On the other hand, the decolonisation and the return of the settlers (shown in O Retorno by Maria Dulce Cardoso) is treated as a crucial point in which the vision of the “Portuguese world” suffered a profound reshaping. It emerges, at the beginning of the 21st century, as a community of the poor in such novels as O Apocalipse dos trabalhadores by Walter Hugo Mãe.

Kultura – Historia – Globalizacja, no 21/2017, p. 149-160. ISSN 1898-7265

http://www.khg.uni.wroc.pl/files/11%20KHG_21%20Lukaszyk%20t.pdf

Reprinted in volume: Historia – Kultura – Globalizacja, vol. VIII, Adam Nobis, Piotr Badyna, Piotr J. Fereński (eds.), Wrocław, Arboretum, 2018, p. 653-666. ISBN 978-83-62563-68-5

The essay comments on the evolution of the Portuguese concept of identity between its medieval and early-modern origins and the decline of the colonial empire. The concept of the “Portuguese world”, exemplified in the exposition organised in 1940, is treated as a simulacrum covering the deficiencies of the colonial project. At the same time, the vindication of the “earth” as opposed to the maritime space of the supposed “paracletic” destiny of the nation, is brought back to the Salazarian epoch with the figure of Henrique Galvão. Portugal is imagined as a garden, in which also the Other is included, as it can still be seen in the collection of "peoples of the empire" decorating the botanical garden in Belem. On the other hand, the decolonisation and the return of the settlers (shown in O Retorno by Maria Dulce Cardoso) is treated as a crucial point in which the vision of the “Portuguese world” suffered a profound reshaping. It emerges, at the beginning of the 21st century, as a community of the poor in such novels as O Apocalipse dos trabalhadores by Walter Hugo Mãe.

| od_morskiego_imperium.pdf | |

| File Size: | 392 kb |

| File Type: | |

Fearful and female. Narrations of anxiety and the boom of the Portuguese fiction written by women in the decade of 1980

|

Romanica Silesiana, no 11 (vol. 2), 2016, p. 82-92. ISSN 1898-2433, e-ISSN 2353-9887

http://www.journals.us.edu.pl/index.php/RS/article/view/6025 The article analyses the importance of the minor genre of horror tale in the development of the Portuguese fiction written by women during the 1980s. It permitted to find a literary expression of the silenced topics, such as the fear of pregnancy and childbirth, domestic violence, prostitution. The narrations of anxiety created by such writers as Luisa Costa Gomes, Maria Ondina Braga, Lídia Jorge, Teolinda Gersão, and Hélia Correia mark a period of transition in the Portuguese culture, questioning both female and male condition. Exploration of the gender perspective leads to the utmost triumph of women that finally achieve recognition in the fields of literature and cultural criticism. At the same time, it contributes to exorcise the spectres of the patriarchal culture that became obsolete after the end of Salazarism and the Portuguese colonial empire.

| |||||||

empire & nostalgia

Imperium i nostalgia. "Styl późny" w kulturze portugalskiej [Empire and Nostalgia. "Late style" in the Portuguese culture], Warszawa, DiG, 2015, 180 pp. ISBN 978-83-7181-960-5

Summary

The main conceptual framework of this book is given by my search for the definition of transcultural condition that the Portuguese never managed to achieve, in spite of their incessant search for universalism. The essays included in it form a chain of ideas recounting the Portuguese cultural history, passing through such key figures as Camões, Vieira, Pessoa and Saramago, to whom this research project has been officially dedicated.

In the Foreword, after some preliminary remarks, I give a working definition of transcultural and transcolonial, as well as situate the Portuguese case in the context of global studies. The first chapter, "Light at dusk" is dedicated to the concept of "late style" that appears in the title, as well as other ideas taken from Edward Said. I return to his evocation of Batinist and Zahirite schools in The Word, the Text and the Critic to search for an analogous dichotomy in the Portuguese literature, namely opposing Vieira and Pessoa on the one hand, and Saramago on the other.

In the second essay, "On the path of hyper-culture", I propose this neologism to grasp the premises and implications of the Portuguese idea concerning the special place of their culture as an "essence of unification", idea that appears in the vision of the "Fifth Empire" in the 17th century and is still present nowadays in the discourse of Lusophony. The main bulk of this chapter is dedicated to Vieira, as I try to confront my concept of transculture and his writings, such as História do Futuro and Clavis Prophetarum. Agamben's seminar on the Letter to Romans, as well as the whole discussion involving Paul and the origins of universalism, appear in the background. Finally, Vieira is confronted with Pessoa and what I call the "virtualization" of the Portuguese universalism.

The third chapter, "In the cycle of catastrophe" parts from the essay Shipwreck with spectator by Hans Blumenberg. The metaphor used by the German philosopher obviously invites a confrontation with the Portuguese maritime destiny. I try to go deeper than this superficial association, taking the dawn of the hyper-culture for the moment of transgression launching the European on the one-way path of progress, identified here with the fulfillment of the globalization. As Blumenberg suggests, the cyclic dynamics of the modern catastrophe, rebuilding the ships with the shipwrecked material, is caused by the incessant temptation of wholeness -- of which the early-modern vision of Vasco da Gama in The Lusiads is a premonition. Going back to the idea of crusade, I speak about the cycle of Portuguese catastrophes, situated quite close to the native shores, in Morocco. On the other hand, the longue durée of the crusade forms a cataclysmic pattern that I call the globalization of the Mediterranean.

The title of the next essay, "Conversation with a skull", is taken from Rushdie's short story included in East, West and refers to the skull of the dead jester Yorick that appears in Hamlet. Since the first moments of their presence in the New World, the Portuguese humanists, such as Pêro Vaz de Caminha and Damião de Góis, appropriate the alien voice, realizing the early-modern pattern of intercession, once again shown through the Shakespearean reference to the figure of Desdemona, causing the tragedy by her obsession of interceding in defense of a plain soldier. The stranger is silenced as the humanists speak loud in his name. The burden of hegemonic situation, of which I spoke in the chapter dedicated to Vieira, creates a longing for otherness' voice and the supposed re-creative potential of genus angelicum. Nonetheless, the eventuality of a native Yorick answering Hamlet causes a thrill that ultimately blocks any attempt at a genuine communication. On the other hand, the simile of the bottom and surface of Narcissus' spring subsumes the search for an alien mirror permitting a glance at the European condition. The chapter on Cannibals in Montaigne's Essays doesn't actually offer this insight; it is found very late, when a Portuguese colonizer discovers his own portrait in the African sculpture of Yaka.

In the next chapter, I return to the messianic imagination contributing to the imperial utopia that survives the decolonization and is to be found in the post-modern constructs of lusophony. I read both the defenders and the adversaries of the new project, seeking to understand the peculiar Portuguese understanding of the notion of spiritual empire that arguably survived unscathed the postcolonial negotiations.

Finally, the last part of the book is dedicated to the contemporary Portuguese culture, featuring Jorge de Sena, Eduardo Lourenço and Saramago. They are seen as "dispatriants" breaking through the limiting patterns of their homeland, reflected in the claustrophobic simile of an island of the leprous. Once again, they search for a new form of intellectual universalism beyond the limitations of the "insular" mentality of the Portuguese. The final remarks on Saramago are placed under the sign of the "victory of Erros". I employ the erotic-erratic concept proposed by the Polish philosopher Agata Bielik-Robson to highlight the earthly liberation achieved after the breakdown of the Portuguese hyper-cultural narration.

The book closes with a "Moral of the story", adopting an external view of the Portuguese culture and evoking its place in non-European memory. Panglima Awang, a short novel by a Malay writer Harun Aminurashid is evoked, leading to a de-centered vision of the global history.

| imperium_i_nostalgia__przedmowa.pdf | |

| File Size: | 262 kb |

| File Type: | |

Review of this book (in Portuguese):

Anna Olchówka, EWA LUKASZYK, Imperium i nostalgia. “Styl późny” w kulturze portugalskiej, Warszawa, Wydawnictwo DIG, 2015, 175 pp., Estudios Hispánicos, vol. 24/2016, p. 198-200.

DOI 10.19195/2084-2546.24.2

Anna Olchówka, EWA LUKASZYK, Imperium i nostalgia. “Styl późny” w kulturze portugalskiej, Warszawa, Wydawnictwo DIG, 2015, 175 pp., Estudios Hispánicos, vol. 24/2016, p. 198-200.

DOI 10.19195/2084-2546.24.2

Universos domésticos na narrativa portuguesa das últimas décadas do século XX: moradas imaginárias no ciclo duma cosmogonia mítica

Familiar universes in the Portuguese narrations during the last decades of the 20th century: imaginary homes in the cycle of mythical cosmogony

Mitologizacje czlowieka w kulturze i literaturze iberyjskiej i polskiej, Wojciech Charchalis, Bogdan Trocha (eds.), Zielona Góra, Pracownia Mitopoetyki i Filozofii Literatury – Uniwersytet Zielonogórski, 2016, p. 167-181.

Mitologizacje czlowieka w kulturze i literaturze iberyjskiej i polskiej, Wojciech Charchalis, Bogdan Trocha (eds.), Zielona Góra, Pracownia Mitopoetyki i Filozofii Literatury – Uniwersytet Zielonogórski, 2016, p. 167-181.

| universos_domesticos.pdf | |

| File Size: | 177 kb |

| File Type: | |

No ventre dum cavalo de Troia. Espaços da criatividade feminina na escrita de Teolinda Gersão

“Inside the belly of a Trojan horse. Spaces of female creativity in the writings by Teolinda Gersão”

Lusorama. Zeitschrift für Lusitanistik, no 103-104, November 2015, p. 6-23. ISSN 0931-9484

Discute-se o problema dos entraves à atividade criadora da mulher, denunciados na escrita de Teolinda Gersão. Um relevo especial é dado ao romance A Cidade de Ulisses e à desconstrução do mito de Ulisses enquanto parte da herança patriarcal portuguesa. Teolinda Gersão acentua a especificidade da arte entendida pela mulher, postulando a sua inscrição no contexto existencial duma vida individual e comunitária, e recusando uma celebração póstuma do génio feminino.

Lusorama. Zeitschrift für Lusitanistik, no 103-104, November 2015, p. 6-23. ISSN 0931-9484

Discute-se o problema dos entraves à atividade criadora da mulher, denunciados na escrita de Teolinda Gersão. Um relevo especial é dado ao romance A Cidade de Ulisses e à desconstrução do mito de Ulisses enquanto parte da herança patriarcal portuguesa. Teolinda Gersão acentua a especificidade da arte entendida pela mulher, postulando a sua inscrição no contexto existencial duma vida individual e comunitária, e recusando uma celebração póstuma do génio feminino.

De gregos a portugueses. A transferência cultural como um problema de consciência crítica na Cidade de Ulisses de Teolinda Gersão

"From Greek to Portuguese. The cultural transfer as a problem of critical consciousness in Cidade de Ulisses, by Teolinda Gersão"

Estudios Hispánicos, vol. XXIII, 2015, p. 173-184. ISSN 0239-6661

The novel A Cidade de Ulisses (2011), written as an answer to the economic crisis, sheds a new light on the relationship between Portugal and Greece. This relationship was very important for the generation living under the regime of Salazar, that looked up to Greece for a model of supranational identity and true civilisation, as opposed to the vision launched by the official propaganda. In her novel, Teolinda Gersao deconstructs one of the myth of the Portuguese identity, the belief that the city of Lisbon had been founded by Ulysses. From a neo-feminist perspective, she criticises the presence of this paradigm in Portuguese culture. At the same time, she deconstructs the idealistic vision of Greece, replacing it by a sounder, more realistic idea of identification and solidarity with Europe's deficient South.

Estudios Hispánicos, vol. XXIII, 2015, p. 173-184. ISSN 0239-6661

The novel A Cidade de Ulisses (2011), written as an answer to the economic crisis, sheds a new light on the relationship between Portugal and Greece. This relationship was very important for the generation living under the regime of Salazar, that looked up to Greece for a model of supranational identity and true civilisation, as opposed to the vision launched by the official propaganda. In her novel, Teolinda Gersao deconstructs one of the myth of the Portuguese identity, the belief that the city of Lisbon had been founded by Ulysses. From a neo-feminist perspective, she criticises the presence of this paradigm in Portuguese culture. At the same time, she deconstructs the idealistic vision of Greece, replacing it by a sounder, more realistic idea of identification and solidarity with Europe's deficient South.

| de_gregos_a_portugueses.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1410 kb |

| File Type: | |

Nós, Portugal, o poder ser. Um universalismo virtual como resultado dum processo de auto-mitificação da cultura

"We, Portugal, the possibility of being. Virtual universalism as the result of the process of cultural self-mythification", Mitologizacja kultury w polskiej i iberyjskiej twórczości artystycznej / Mitificação de cultura na criação artística ibérica e polaca, Wojciech Charchalis, Bogdan Trocha (eds.), Zielona Góra, Pracownia Mitopoetyki i Filozofii Literatury - Uniwersytet Zielonogórski, 2015, p. 287-297. ISBN 978-83-940506-8-9

“ |

[...] Pessoa, baseando-se nos passos de virtualização que já foram dados anteriormente na história da cultura portuguesa, estabelece uma versão mais completa do universalismo virtual, que contrapõe, de certa forma, aos dados geopolíticos do seu tempo, em que o império colonial britânico predomina num mundo real, empurrando Portugal para um estatuto semi-periférico. No entanto, numa intuição genial, vislumbra a resiliência excecional deste império tão fraco que aparentemente nem chegava a ser uma verdadeira potência colonial, assim como o Ultimato inglês em 1890 o tinha provado. Como comenta Eduardo Lourenço, “o sentimento profundo da fragilidade nacional – e o seu reverso, a ideia de que essa fragilidade é um dom, uma dádiva da própria Providência, e o reino de Portugal uma espécie de milagre contínuo, expressão da vontade de Deus – é uma constante da mitologia, não só histórico-política, mas também cultural portuguesa”.

|

| nos_portugal_o_poder_ser.pdf | |

| File Size: | 228 kb |

| File Type: | |

Moss, peat and coal. The chest with thirty thousand sheets of paper by Fernando Pessoa

“Mech, torf i węgiel. O skrzyni z trzydziestoma tysiącami świstków Fernanda Pessoi”, Tekstualia, no 2(37)/2014, p. 99-110. ISSN 1734-6029

The figure of Fernando Pessoa as we know him today results from a double work-in-progress: firstly, by the poet himself, who, instead of preparing his own work for publication, collected spare sheets of paper in the famous chest (“arca”), and secondly, by the researchers, who, year by year, go on publishing successive volumes derived from that legacy. In a sense, Pessoa is thus our contemporary, as the meanings acquired by his published writings follow the current trends in humanities.

The “arca” is interpreted as the result of an intentional project realized by the writer who preferred a collection of spare sheets over a definitive shape of a book published in its author's lifetime. The chest reflects the idea of a library in ruins, overflowing abundance of spare pages and de-contextualized ideas; their potential meaning is constantly re-actualized as an expedient form of order introduced into the chaos. Through this project, the Portuguese poet avoids the fate of the peripheral condition that would otherwise condemn him to eternal belatedness in relation to the modern movements and poetics.

The figure of Fernando Pessoa as we know him today results from a double work-in-progress: firstly, by the poet himself, who, instead of preparing his own work for publication, collected spare sheets of paper in the famous chest (“arca”), and secondly, by the researchers, who, year by year, go on publishing successive volumes derived from that legacy. In a sense, Pessoa is thus our contemporary, as the meanings acquired by his published writings follow the current trends in humanities.

The “arca” is interpreted as the result of an intentional project realized by the writer who preferred a collection of spare sheets over a definitive shape of a book published in its author's lifetime. The chest reflects the idea of a library in ruins, overflowing abundance of spare pages and de-contextualized ideas; their potential meaning is constantly re-actualized as an expedient form of order introduced into the chaos. Through this project, the Portuguese poet avoids the fate of the peripheral condition that would otherwise condemn him to eternal belatedness in relation to the modern movements and poetics.

| mech_torf_i_wegiel.pdf | |

| File Size: | 599 kb |

| File Type: | |

Sangue e leite. A transmutação andrógina no Físico prodigioso de Jorge de Sena

"Blood and Milk. Androgynous transmutation in O Físico prodigioso, by Jorge de Sena"

Estudios Hispánicos, XXI, 2013, p. 121-131. ISSN 2084-2546; e-ISSN 2545-0980

Also available online in: Ler Jorge de Sena (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro):

http://www.lerjorgedesena.letras.ufrj.br/sem-categoria/novo-sangue-e-leite-a-transmutacao-androgina-no-fisico-prodigioso-de-jorge-de-sena/

To read O Físico prodigioso as an autobiography, according to the explicit recommendation given by the author, seems a difficult task. Nonetheless, the notion of androgyny, appearing in a larger context of reflection on sexuality and gender led by Jorge de Sena, may give an interpretative key to this text, specially if it is considered in the light of his scholarly interests and writings. The intertextual games in O Físico prodigioso give depth to the message concerning sexuality: it should be transcended into androgynous condition, associated with the plenitude of creative powers and the domain of the sacred.

Estudios Hispánicos, XXI, 2013, p. 121-131. ISSN 2084-2546; e-ISSN 2545-0980

Also available online in: Ler Jorge de Sena (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro):

http://www.lerjorgedesena.letras.ufrj.br/sem-categoria/novo-sangue-e-leite-a-transmutacao-androgina-no-fisico-prodigioso-de-jorge-de-sena/

To read O Físico prodigioso as an autobiography, according to the explicit recommendation given by the author, seems a difficult task. Nonetheless, the notion of androgyny, appearing in a larger context of reflection on sexuality and gender led by Jorge de Sena, may give an interpretative key to this text, specially if it is considered in the light of his scholarly interests and writings. The intertextual games in O Físico prodigioso give depth to the message concerning sexuality: it should be transcended into androgynous condition, associated with the plenitude of creative powers and the domain of the sacred.

| sangue_e_leite.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1193 kb |

| File Type: | |

“O czym śnią małe narody? Saramago i tożsamość portugalska w dobie postkolonialnej” [“Small nations' dreams. Saramago and the Portuguese identity in post-colonial times”], Świat powieści José Saramago, Wojciech Charchalis (ed.), Poznań, Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, 2013, p. 15-28. ISBN 978-83-232-2587-4 ISSN 0554-8187 |

temptation of the desert

Pokusa pustyni. Nomadyzm jako wyjście z kryzysu współczesności w pisarstwie José Saramago [Temptation of the Desert. Nomadism as a solution for the contemporary crisis in the novelistic works of Jose Saramago], Kraków, Universitas, 2005, 360 pp.

ISBN 83-242-0563-2

ISBN e-book: ISBN 97883-242-1163-0

The aim of this book is to offer a synthetic vision of the complex theologico-anthropological and political position formulated by José Saramago in his novels, from Manual de Pintura e Caligrafia till O Homem Duplicado.

As a novelist, José Saramago gives a complex picture of the human condition in the world. It is determined by agonistic relations: on the one hand, a conflict between human beings and the tyrannical deity who strives to crush them, on the other – a feud among human beings themselves. History, therefore, appears to be a cyclical pattern of recurring tragedies and injustice.

A point of departure for the reflection is the impossibility to formulate a theodicy. The evil experienced by human beings is shown to be an outrage, a source of unassuaged horror. There is, however, a recipe for solving the dual conflict with the Other (another man or the deity): abandonment of the settled way of life, of manufacturing and accumulating material goods. Only extreme ascetism could remedy the human condition, eliminating the rivalry between the manufacturer and the Maker and disrupting the network of relations which entangle man in the historical human world. The way to avoid being enmeshed in relationship which, in Saramago’s opinion, always threatens with conflict, is nomadism: averting of the gaze, no longer meeting the gaze of the Other – either a rival human being or the jealous Eye of Providence. While looking at the Other, man sees an opponent, which gives rise to the agonistic relation. It is better, then, to view the world disinterestedly during an endless journey.

The first part of the book presents the situation of man facing the deity, tragically determined by disproportion between the heavenly power and the insignificant human world on the one hand and, on the other, by similarity between the participants of the conflict – similarity which incites God’s jealousy of human beings, for they, on their diminutive scale, may be achieving something unattainable to God in all his might. Human beings rebel and overcome their mortality, fulfilling themselves in parenthood and material, literary or musical achievement. The jealous Maker never stops trying to thwart their creative plans, to destroy the order they strive to establish, to stifle their words and their music which is not a reflection of harmony of the spheres but a revolt against the silence of God’s universe. The deity disrupts their work, uproots them, forces them on their way. The ultimate advice that can be given to the tormented human beings crushed in their struggle against the invincible enemy is to accept the necessity, to relinquish the hubris of manufacturing and to undertake the imposed journey.

The second part presents Saramago’s battle against politics and history. It appears that here too, one cannot trust promises. Neither religion nor political revolution leads to a better world. The Western world, based on individualism, is headed for collapse, since the individual identity does not provide a sufficiently stable foundation. Faith in reason is equally illusory and deceptive as faith in divine providence. Rational methods cannot prevent wrongs, and intellectual cognition not only fails to solve real problems but it also proves unable to strengthen morality or eliminate violence which is a basic modus of one human being meeting another. Democracy does not survive, either. This rational system of co-deciding is demonstrated to be a mere cover for ambitions of the most aggressive and an endorsement of the powerlessness and incapacitation of an individual in society. Voting gives only an illusion of responsibility, so the day comes when almost every voter casts an empty ballot into the box.

The nation as a system of solidarity also turns out to be a fiction aimed at concealing centuries-old inequity. Moreover, national history cannot be rectified; it is even impossible to do justice to victims of the past. Consequently, the national community is just another kind of relationship to be dissolved. A micro community, loose group of people, remains the only true form of social life. Only in such minimalist circumstances may the simplest kinds of responsibility be expected, though tentatively so, with no assurance.

History, then, is a problem to be solved. Recurring maladies cannot be remedied with historical methods, as history consists of ever returning, unchanging situations of violence. Permanent improvement can solely be attained in an messianic way, through an apocalyptic closing of history and establishment of an eternal kingdom of nomads who relinquish any rational or technological control over the world, who no longer appropriate anything nor enter relations with other people. Contrary to declarations made outside literature, therefore, the political recipe Saramago proposes is not Marxism as a strictly defined doctrine but going beyond the domain of politics.

The final part of the book elaborates on the metaphor of the desert appearing in the title. The desert is an area free from works of human hands and mind, a place of rest where the menacing deity, faced with human quietism, finds no grounds for rivalry. Thus, hell – that is, the world – becomes familiarized. Man stops fighting the lost battle against time and expanding chaos. Architecture changes into ruin, an indistinct sign. Meticulously organized archives fall apart. All archiving must be abandoned. The eye of the camera, which was supposed to serve as an extension of human sight and memory, proves to be completely useless. Human beings need to reject the instrument and undertake a journey, trying to see the world through their own eyes. They need to give up their passion for cartography and, instead of attempting to control and exploit the changing world, they need to wander without maps, accept the feeling of being lost, and rely on their instinct. Nomads are people without names, possessions or relationships with others, people without plans. They have liberated themselves from the burden of both past and future. Living in the constant now, they are free from history.

The minimalist solutions suggested by Saramago are a response to his radical assessment of Western culture. They arise from the state of utter helplessness, and it is only in such circumstances that they may be accepted. They constitute a call for betrayal, for rejection of one’s cultural heritage – a call made in hope that this radical act will give us the power to return to the auroral moment, to begin everything anew and thus to rebuild the world without its flaws. For those stuck at a dead end, the only course of action is to shift into reverse. This proposal, oscillating so dangerously between utopia and anti-utopia, between a promise and a threat, raises inevitable doubts and reservations. It is valid only in the context of powerlessness of literature, of a game without translation into reality which Saramago tries in vain to modify, searching, as the Neorealists did, for literature aimed at transforming the world. To cast literature in such an elevated role, however, means only another level of the cultural game, and the ultimate lesson to be learned from Saramago’s call for betrayal of Europe and, further, of Western culture, seems to be the affirmation of remaining faithful.

the territory & the world

Terytorium a świat. Wyobrażeniowe konfiguracje przestrzeni w literaturze portugalskiej od schyłku średniowiecza do współczesności [The Territory and the World. Imaginary configurations of space in Portuguese literature since the end of the Middle Ages till the contemporary period], Kraków, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 2003, 290 pp.

ISBN 83-233-1680-5

Summary

The book presents an analysis of space categories in Portuguese literature across the "imperial cycle", i.e. an extensive epoch that goes from the passage from Middle Ages to early modernity till the contemporary period. The main aim is to put in the limelight the evolution of spatial conceptualization, built up around two crucial notions: that of the "territory" and that of the "world". These two crucial concepts are in constant interaction along the Portuguese history, leading to their paradoxical identification in the concept of the "Fifth Empire" introduced by a 17th century Jesuit, António Vieira, who dreamed about a universal state unifying all humanity.

The five extensive chapters of this book show different aspects or stages in the development of the Portuguese spatial imagination. The first chapter, "Crossing the borders, seeing and reorganizing the world" starts with the teophanic root of the Portuguese identity, based on the narration of "milagre do Ourique". The maritime expansion is thus inscribed in the context of the "sacred mission" determining and justifying the existence of the nation. The legitimizing narration given by Camões in The Lusitans is one of the main points of this chapter. As a consequence, the paradigm of homo viator is conceptualized as the ideal realization of the human potential.

With the second chapter, "Unification of the world", we enter in the full blossom of the Portuguese idealistic project of the universal spiritual empire. I show the interplay of two apparently heterogeneous aspects: the vision of universalism elaborated by the humanists and the "Fifth Empire" of António Vieira. These two aspects contribute to the crystallized vision of humanity unified by the Portuguese in a new, at the same time political and mystic reality. Breaking the chronological order of the book, this chapters brings about Fernando Pessoa as the 20th century culmination of the vision of the Portuguese spiritual empire.

The beginning of the third chapter, "Unified world falling apart" takes the reader back to the early modern history, dealing with the negative aspects of the expansion. It presents the testimonies of being lost in the hostile world that make an important part of the Portuguese experience. A highlight in the presented material is given to the narrations of shipwrecks collected in História Trágico-Marítima. The analysis continues across the Portuguese literary history, culminating once again in the narrations of the African colonial war.

The last two chapters deal with modernity, marked by the destruction of the sacralised vision of the Portuguese destiny. This degradation of the consciousness of sacred mission that legitimised the very existence of the nation in earlier centuries is translated by visions of illness and degeneration of the national space, mainly in the literature created in the second half of the 19th century. What emerges during this century is the painful consciousness of contradiction between the supposed hegemonic and messianic mission in the world and the actual insignificance and poverty of the continental territory. Nonetheless, the generation of saudosistas brings back the idealised images of Portuguese homeland. Across this period, the negotiation of status between Portugal and Europe requires a new spatial category, that of periphery. Finally, the survey of the Portuguese spatial imagination culminates in Saramago's understanding of nomadism that obliterates both the hyperbolic notion of empire and the painful consciousness of periphery.

ISBN 83-233-1680-5

Summary

The book presents an analysis of space categories in Portuguese literature across the "imperial cycle", i.e. an extensive epoch that goes from the passage from Middle Ages to early modernity till the contemporary period. The main aim is to put in the limelight the evolution of spatial conceptualization, built up around two crucial notions: that of the "territory" and that of the "world". These two crucial concepts are in constant interaction along the Portuguese history, leading to their paradoxical identification in the concept of the "Fifth Empire" introduced by a 17th century Jesuit, António Vieira, who dreamed about a universal state unifying all humanity.

The five extensive chapters of this book show different aspects or stages in the development of the Portuguese spatial imagination. The first chapter, "Crossing the borders, seeing and reorganizing the world" starts with the teophanic root of the Portuguese identity, based on the narration of "milagre do Ourique". The maritime expansion is thus inscribed in the context of the "sacred mission" determining and justifying the existence of the nation. The legitimizing narration given by Camões in The Lusitans is one of the main points of this chapter. As a consequence, the paradigm of homo viator is conceptualized as the ideal realization of the human potential.

With the second chapter, "Unification of the world", we enter in the full blossom of the Portuguese idealistic project of the universal spiritual empire. I show the interplay of two apparently heterogeneous aspects: the vision of universalism elaborated by the humanists and the "Fifth Empire" of António Vieira. These two aspects contribute to the crystallized vision of humanity unified by the Portuguese in a new, at the same time political and mystic reality. Breaking the chronological order of the book, this chapters brings about Fernando Pessoa as the 20th century culmination of the vision of the Portuguese spiritual empire.

The beginning of the third chapter, "Unified world falling apart" takes the reader back to the early modern history, dealing with the negative aspects of the expansion. It presents the testimonies of being lost in the hostile world that make an important part of the Portuguese experience. A highlight in the presented material is given to the narrations of shipwrecks collected in História Trágico-Marítima. The analysis continues across the Portuguese literary history, culminating once again in the narrations of the African colonial war.

The last two chapters deal with modernity, marked by the destruction of the sacralised vision of the Portuguese destiny. This degradation of the consciousness of sacred mission that legitimised the very existence of the nation in earlier centuries is translated by visions of illness and degeneration of the national space, mainly in the literature created in the second half of the 19th century. What emerges during this century is the painful consciousness of contradiction between the supposed hegemonic and messianic mission in the world and the actual insignificance and poverty of the continental territory. Nonetheless, the generation of saudosistas brings back the idealised images of Portuguese homeland. Across this period, the negotiation of status between Portugal and Europe requires a new spatial category, that of periphery. Finally, the survey of the Portuguese spatial imagination culminates in Saramago's understanding of nomadism that obliterates both the hyperbolic notion of empire and the painful consciousness of periphery.

Bolseira da Semana on the Gulbenkian Connect

Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (F.C.G) – How did the Gulbenkian Scholarship change my life?

Ewa A. Łukaszyk (E. Ł.) – I have been a Gulbenkian scholar twice, in 1998/1999 and 2016/2017. Both were turning points of my career in Portuguese and Lusophone studies, although in quite different ways. In 1998, I was a newly established instructor of Portuguese at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, still working for my Ph.D. dissertation on domestic universes created by such writers as Vergílio Ferreira, Carlos de Oliveira, Sophia de Mello Breyner, Lídia Jorge and Teolinda Gersão. But my Gulbenkian Scholarship helped me for more than just this. I could participate in the postgraduate programme in Comparative Literature (Mestrado em Literatura Comparada) at the University of Lisbon, which completely changed my perspective on the relationship between literature and other modalities, such as visual representation of the world in art.

F.C.G – Where am I and where am I going?

E.Ł. – For many years, I was primarily committed with my national area, trying to bring the knowledge about language, literature and history of Portugal closer to the academic and non-academic readers in Poland. I started in 1997 with a popular Portuguese grammar which, twenty years later, is still available in language bookshops. I continued with various translations, including a history of Portugal by José Hermano Saraiva. Overall, I authored five books and over sixty papers and articles on Portuguese literature and culture, most of them written in Polish. Naturally, as my career progressed, I became increasingly committed with international scholarship, as well as broader, comparative approaches aiming at theoretical innovation in cultural studies. Nonetheless, my Portuguese experience remains a crucial ingredient of any such endeavour. Just to give an example, the project on Adamic language that I developed in 2017/2018 as a Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellow in France, while presenting a vast panorama of the search for pre-lapsarian language spoken in Paradise that preoccupied Islamic, Judaic and Christian scholars scattered across the medieval and early-modern Mediterranean world, found a culminating point in João de Barros. The Portuguese humanist believed that the words of the perfect language spoken before the fall of the tower of Babel were still remembered, although dispersed among various peoples of the world. The Portuguese maritime expansion might thus permit to bring them together, in such a way that man could speak again the language of angels. After a long stay in the Netherlands, I am back in France, working on a project “Mystical heritage and cultural transgression in the contemporary Euro-Mediterranean writing” at the CY Advanced Studies institute in Cergy (Parisian region). The title may sound both cryptic and distant from my Portuguese experience. Nonetheless, the mystical heritage that I study in the present-day Francophone novels is intimately connected with Portuguese past. Although the most famous of those mystics, such as Ibn Arabi, were connected to major urban centres located in today's Spain, they built up their spiritual adventure on the teachings of obscure, rural, often illiterate Sufi masters that had once trodden the Portuguese soil.

F.C.G – Can you tell a lesson for anyone who wants a career in your area?

E.Ł. – Till now, I have walked a long way in Portuguese studies. One may also say I have walked in circles around the Portuguese studies, perhaps at a growing distance from the centre. Yet I believe this is exactly the most important lesson for anyone who pretends to achieve academic excellence in my area. Portuguese culture is so profoundly connected to the notion of opening horizons that the most efficient way to study it is to adopt, since the very beginning, a global, comparative perspective. Treat Portugal as a key to the world.

Ewa A. Łukaszyk (E. Ł.) – I have been a Gulbenkian scholar twice, in 1998/1999 and 2016/2017. Both were turning points of my career in Portuguese and Lusophone studies, although in quite different ways. In 1998, I was a newly established instructor of Portuguese at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, still working for my Ph.D. dissertation on domestic universes created by such writers as Vergílio Ferreira, Carlos de Oliveira, Sophia de Mello Breyner, Lídia Jorge and Teolinda Gersão. But my Gulbenkian Scholarship helped me for more than just this. I could participate in the postgraduate programme in Comparative Literature (Mestrado em Literatura Comparada) at the University of Lisbon, which completely changed my perspective on the relationship between literature and other modalities, such as visual representation of the world in art.

F.C.G – Where am I and where am I going?

E.Ł. – For many years, I was primarily committed with my national area, trying to bring the knowledge about language, literature and history of Portugal closer to the academic and non-academic readers in Poland. I started in 1997 with a popular Portuguese grammar which, twenty years later, is still available in language bookshops. I continued with various translations, including a history of Portugal by José Hermano Saraiva. Overall, I authored five books and over sixty papers and articles on Portuguese literature and culture, most of them written in Polish. Naturally, as my career progressed, I became increasingly committed with international scholarship, as well as broader, comparative approaches aiming at theoretical innovation in cultural studies. Nonetheless, my Portuguese experience remains a crucial ingredient of any such endeavour. Just to give an example, the project on Adamic language that I developed in 2017/2018 as a Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellow in France, while presenting a vast panorama of the search for pre-lapsarian language spoken in Paradise that preoccupied Islamic, Judaic and Christian scholars scattered across the medieval and early-modern Mediterranean world, found a culminating point in João de Barros. The Portuguese humanist believed that the words of the perfect language spoken before the fall of the tower of Babel were still remembered, although dispersed among various peoples of the world. The Portuguese maritime expansion might thus permit to bring them together, in such a way that man could speak again the language of angels. After a long stay in the Netherlands, I am back in France, working on a project “Mystical heritage and cultural transgression in the contemporary Euro-Mediterranean writing” at the CY Advanced Studies institute in Cergy (Parisian region). The title may sound both cryptic and distant from my Portuguese experience. Nonetheless, the mystical heritage that I study in the present-day Francophone novels is intimately connected with Portuguese past. Although the most famous of those mystics, such as Ibn Arabi, were connected to major urban centres located in today's Spain, they built up their spiritual adventure on the teachings of obscure, rural, often illiterate Sufi masters that had once trodden the Portuguese soil.

F.C.G – Can you tell a lesson for anyone who wants a career in your area?

E.Ł. – Till now, I have walked a long way in Portuguese studies. One may also say I have walked in circles around the Portuguese studies, perhaps at a growing distance from the centre. Yet I believe this is exactly the most important lesson for anyone who pretends to achieve academic excellence in my area. Portuguese culture is so profoundly connected to the notion of opening horizons that the most efficient way to study it is to adopt, since the very beginning, a global, comparative perspective. Treat Portugal as a key to the world.