what is Syrian literature?

The antiquity of Syrian literature is frequently underestimated. Actually, the corpus of Ugaritic texts that may be seen as the oldest Syrian literature, written in cuneiform script, dates back to 13th and 12th century BC, which is considerably older than Homer. This literature, expressed in a Northwest Semitic language, is represented by some fifty epic poems associated with the Cycle of Baal, the Legend of Keret (the Epic of Kirta), and the Tale of Aqhat.

Of course, the identity of the modern country called Syria emerged progressively around Damascus and other city centres, many of them belonging to the oldest urban tradition on Earth.

Before the Arab conquest, the country knew the heyday of Syriac literature, i.e. a body of writing in eastern Aramaic, a Semitic language originally spoken in the region of Edessa. In early centuries of the Christian era, it spread across the Middle East due to the status of Edessa on the map of the Christian Orient. From the 7th century on, it also played an important role as the intermediary between ancient Greek and the Islamic world. It is illustrated by such authors as the Christian poets St. Ephraem Syrus (4th c.) and the Nestorian Narsai (5th c.). There existed an important Syriac historiography, epitomised by the patriarch Michael I.

The medieval Arabic-speaking Syria knew its early heyday with the Umayyads and an early encounter with Europe through the Crusader states. The biography of Usama ibn Munkidh offers a vivid account of that early cross-cultural encounters.

Later on, the country fell down to a provincial role in the Ottoman Empire. From 1920 to 1948, Syria was under French rule.

The most famous of the country's contemporary poets is Adonis (pen name of Ali Ahmad Said Esber, born in 1930), the great modernizer of Arabic poetry. Nonetheless, many scholars speak of the "silence" of the contemporary Syrian literature, even before the war.

Of course, the identity of the modern country called Syria emerged progressively around Damascus and other city centres, many of them belonging to the oldest urban tradition on Earth.

Before the Arab conquest, the country knew the heyday of Syriac literature, i.e. a body of writing in eastern Aramaic, a Semitic language originally spoken in the region of Edessa. In early centuries of the Christian era, it spread across the Middle East due to the status of Edessa on the map of the Christian Orient. From the 7th century on, it also played an important role as the intermediary between ancient Greek and the Islamic world. It is illustrated by such authors as the Christian poets St. Ephraem Syrus (4th c.) and the Nestorian Narsai (5th c.). There existed an important Syriac historiography, epitomised by the patriarch Michael I.

The medieval Arabic-speaking Syria knew its early heyday with the Umayyads and an early encounter with Europe through the Crusader states. The biography of Usama ibn Munkidh offers a vivid account of that early cross-cultural encounters.

Later on, the country fell down to a provincial role in the Ottoman Empire. From 1920 to 1948, Syria was under French rule.

The most famous of the country's contemporary poets is Adonis (pen name of Ali Ahmad Said Esber, born in 1930), the great modernizer of Arabic poetry. Nonetheless, many scholars speak of the "silence" of the contemporary Syrian literature, even before the war.

I have readSalwa Al Neimi, Burhān al-ʿasal | The Proof of the Honey (2007)

Usamah ibn Munkidh, Kitab al-i'tibar (12th c.) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have written... nothing ...

|

my Syrian travel before the war

I visited Syria in February 2010, just months, if not weeks, before the beginning of the unrest that utterly led to the civil war. This is why the memory of this travel weighed heavily in me, by the idea that most travels are just squeezed between one conflict and another. And even at that moment, Bosra made a particularly grim impression on me. Not just by the basaltic aspect of the city; also by a particular poverty of its inhabitants. There are different kinds of poverty, characterised by different types of absence. In Bosra, as I saw it, the absence was beyond the material things. It was a deeper, more essential lack of reason to exist, a sort of suspension in the history.

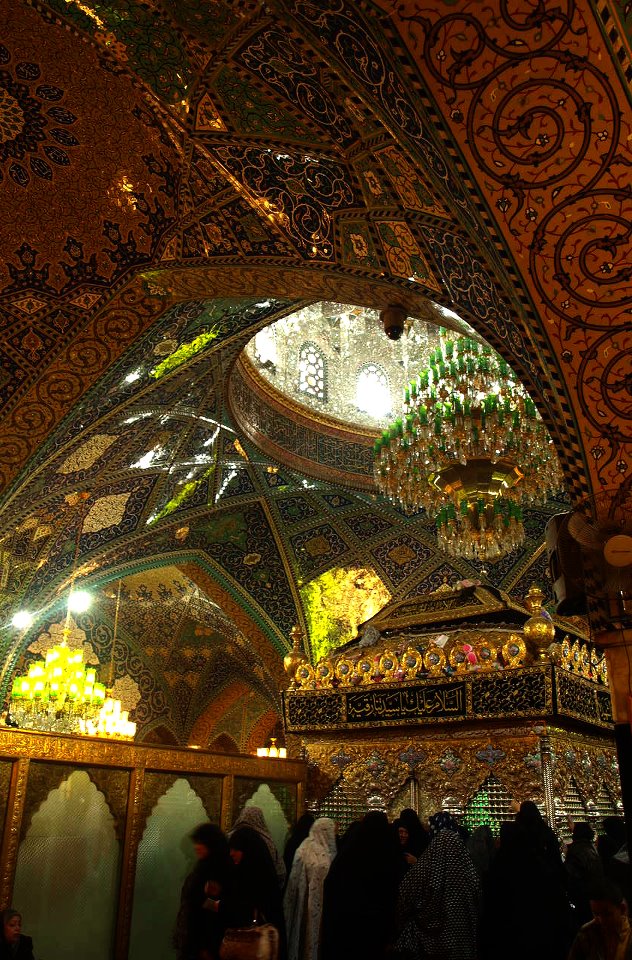

I also visited other places, those musts of a European grand tour: Krak des Chevaliers, Palmyra, Damascus with its Omayyad mosque and the old city. How much do I regret not having seen more!... And also, not having been kinder, more generous to the country's inhabitants, children of ten selling postcards on the sites, green-eyed adolescents attempting to establish any sort of contact, in view of who knows what future.

I also visited other places, those musts of a European grand tour: Krak des Chevaliers, Palmyra, Damascus with its Omayyad mosque and the old city. How much do I regret not having seen more!... And also, not having been kinder, more generous to the country's inhabitants, children of ten selling postcards on the sites, green-eyed adolescents attempting to establish any sort of contact, in view of who knows what future.

reading Syrian literature

knights and falcons

Usamah ibn Munqidh in his autobiography, Kitab al-I’tibar (Book of learning by example) studied and translated by Philip K. Hitti, gives an image of the Holy Land dominated by Christian invasion. This Muslim warrior and courtier living in the times of the Crusades (1095-1188) was the son of the educated emir of Shaizar, a miniature state in the vicinity of Aleppo. His life was filled by wars, travels and hunting. As a member of the social elite of that time, he used to maintain close relationships with important figures among both, Muslims and Christians. He was a friend of the great Salah ad-Din and of the king of Jerusalem, Fulk. If we believe Usamah’s own words, he was bound by mutual ties of amity with numerous European knights. In his autobiographical book, falconry furnish a constant background for those social relationships, crossing over an ideological gap that could seem impossible to transverse.

One of striking moments of this quite singular autobiography is the burial of a beloved she-falcon, complete with Qur'an recitations and a lot of weeping, organized by Usamah's friend; to such a degree that he believed it was the burial of the friend's own daughter. Reading the narration concerning the relationship with the falcon one can detect rather curious traces of the “culturalization” of the natural behaviour of the bird, as observed by its human partner. Just to give an example, the Syrian falconer interpreted the fact that the falcon didn't attack the fowl in the courtyard as the proof that the bird understood and shared the basic cultural distinctions and concepts, such as “home” and “domestic” versus “alien”, “outsider”, “wild” or “stranger”.

Usamah Ibn Munkidh, Kitab al-I'tibar (Book of Learning by Example), ed. Philip K. Hitti, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1930.

One of striking moments of this quite singular autobiography is the burial of a beloved she-falcon, complete with Qur'an recitations and a lot of weeping, organized by Usamah's friend; to such a degree that he believed it was the burial of the friend's own daughter. Reading the narration concerning the relationship with the falcon one can detect rather curious traces of the “culturalization” of the natural behaviour of the bird, as observed by its human partner. Just to give an example, the Syrian falconer interpreted the fact that the falcon didn't attack the fowl in the courtyard as the proof that the bird understood and shared the basic cultural distinctions and concepts, such as “home” and “domestic” versus “alien”, “outsider”, “wild” or “stranger”.

Usamah Ibn Munkidh, Kitab al-I'tibar (Book of Learning by Example), ed. Philip K. Hitti, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1930.