I have readAbdelwahab Meddeb, Le Printemps de Tunis (2013)

Albert Memmi, Le Pharaon (1988) Al-Nefzawi, الروض العاطر في نزهة الخاطر | The Perfumed Garden (15th c.) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have writtenIs there Tunisian literature?

|

a decolonial pharaoh

Albert Memmi (1920-2020) seems a man of other times, friend of French existentialists, author of Portrait du colonisé, précédé de portrait du colonisateur (1957), famous mainly for his early novels, such as La statue de sel (1953). Le pharaon, published for the first time in 1988, is a kind of decolonial memoir, returning, with a certain taste of melancholy, to the somnolent, rather shallow and reckless life of the old Tunis, in which the idea of independence suddenly bursts, almost like a bomb. The novelistic matter is, in a great measure, an uncompromising transcript of the discussions led at the time, on the multiethnicity of the colonial city and country, on Jewishness, on political indolence. An Oriental life, shortly speaking, to such a degree that, were it written by a European, the author would be accused of reproducing orientalising stereotypes. The hero, Armand Gozlan, an archaeologist and a trader in curios and antiquities, builds his life as solid, static and closed as a pyramid. His characteristic reading are such books as Siècles obscurs du Maghreb (p. 29). Those Tunisians are by no means obscurantist, to the contrary; the novel shows a certain cultural elite, interested in history, art, even nurturing certain intellectual ambitions, such as the study of an obscure ancient kingdom of Gourara; nonetheless, it is precisely the adjective "obscure" that becomes pivotal. Berthe, Gozlan's daughter, is bulimic and obese, apparently sinking in the same, essentially static and ponderous existence, symbol of the local society. Yet suddenly, something moves.

Albert Memmi, Le Pharaon, Paris, Éditions du Félin, 2001.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 9.06.2021.

Albert Memmi, Le Pharaon, Paris, Éditions du Félin, 2001.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 9.06.2021.

my adventures in Tunisia

|

I've visited this popular, apparently so accessible destination only once, in the summer 2012. My interest was first of all related to the Islamic past, including Ibn Khaldun, the mosque of Kairouan, etc. In the second place, I was interested in the Tunisian francophone literature, even if I considered it as lesser, not so important as the Moroccan or the Algerian ones. This is why my concern in Tunisia became focused on just one figure: Abdelwahab Meddeb as a writer and as an intellectual. I've published since several papers that mention him, but still a lot remains to be done.

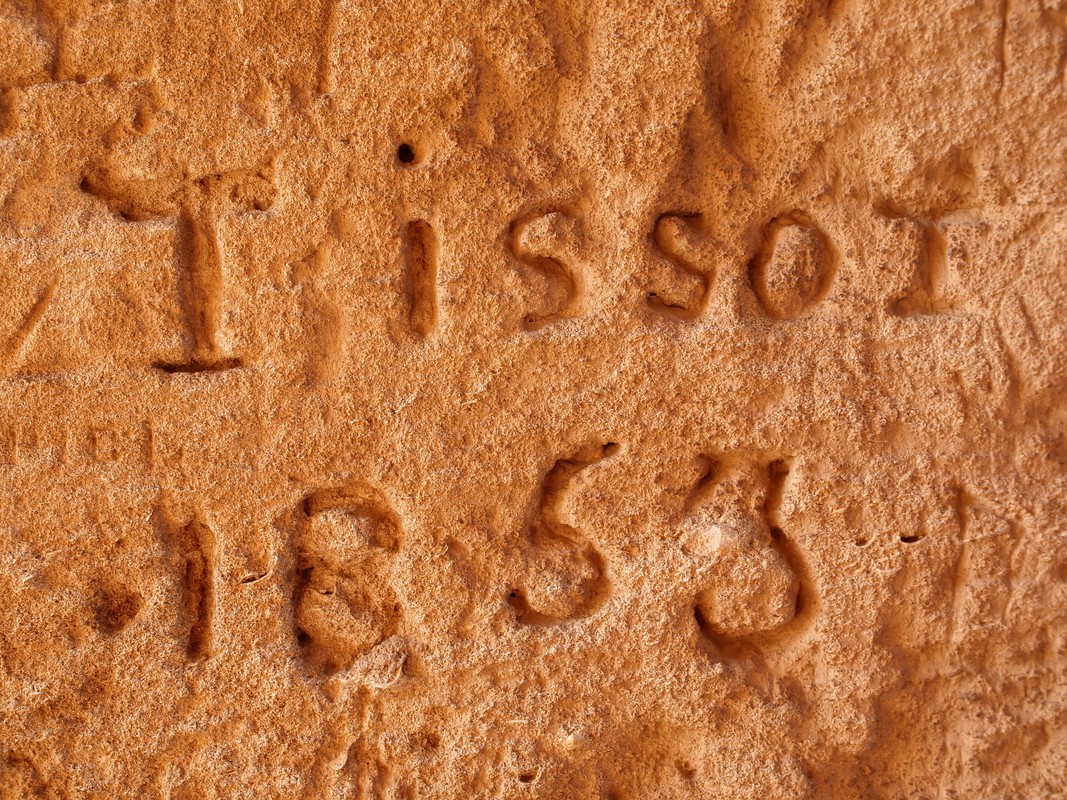

During my trip, I visited the obvious places such as Tunis, with its colonial, modernist Ibn Khaldun Avenue, and the medinah containing the mosque of al-Zaytuna, as well as Kairouan. As I said, the Islamic monuments were at the centre of my interest. Nonetheless, at that time, a certain tension was already in the air for anything that concerned religion. In many places I didn't dare more than a glimpse, hardly daring to breath and certainly not thinking about taking pictures. Al-Zaytuna was one of them. On the other hand, I still had several very friendly encounters with the local religious-intellectual class, as well as with simple people, greatly surprised to see me reading, in bilingual edition, the epistle on Mālikī rite by Ibn Abi Zayd al-Qayrawani. Nonetheless, it was not like in Morocco, where I was often treated with veneration, and aided in any endeavour, due to sheer holiness of my condition as a scholar travelling in search of knowledge; this help and respect was usually coming precisely from very religious people. But in Tunisia it was sensibly not the same; except for an old man in Kairouan who led me to the Mosque of the Three Gates in the middle of a scorching afternoon, just for God's sake. I was more at ease, but at the same time much more isolated from the local life, in sites related to Antiquity; those seemed to have been left entirely for the tourists; although in fact later on the serious trouble arouse in such an apparently neutral place as the Bardo museum. I visited all the obvious attractions such as Carthage, the amphitheatre of El Jam, etc. I also enjoyed the remarkable quality of life, the kind of life created, since the colonial times, for the Europeans. But that wasn't the main aim of my trip. Shortly speaking, Tunisia is a fascinating country that remains on my agenda for a deeper approach, hopefully in quieter times. I didn't feel there at home, as I often do in Morocco; I was a stranger, a European without any excuse to be there, and I rode my camel in Douz as if we were still somewhere between the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. Yes, even if it seems such a popular touristic destination, and worse, a destination of a brainless mass tourism. But that's on the shore, in the hotels near the beach. In the labyrinth of Kairouan's medinah, life remains something else, with very unclear rules across troubled and uneasy times. |

|

Kairouan

The Aghlabid basins

The Aghlabids were a dynasty ruling al-Ifriqiya, i.e. the part of the Maghreb that included Tunisia, but also a part of Algeria and Tripolitania, in 808-909. Banu al-Aghlab are considered Arabs belonging to the Tamim tribe (those who still live today in Saudi Arabia and in Qatar). They came to power after the period of troubles that followed the Berber revolt of 740. They formed a semi-independent emirate ruling in the name of the Abbasids, till they were removed by the Fatimids in 909. They also ruled Sicily (827-902).

Those famous basins, build in 860-862 outside the walls of Kairouan, are regarded as one of the great hydraulic achievements of the time. They are the reminder of some 15 such constructions, destined to provide water supply for the city.

Those famous basins, build in 860-862 outside the walls of Kairouan, are regarded as one of the great hydraulic achievements of the time. They are the reminder of some 15 such constructions, destined to provide water supply for the city.

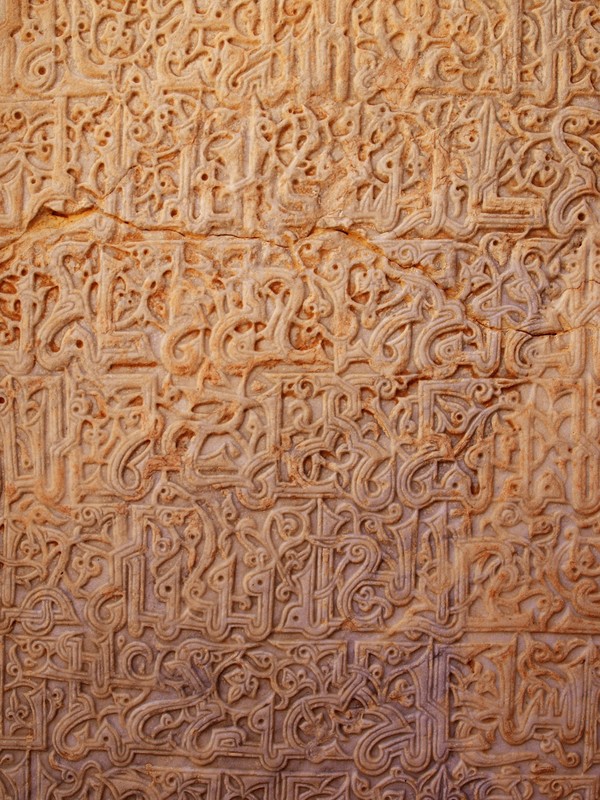

Uqba, the Great Mosque of Kairouan

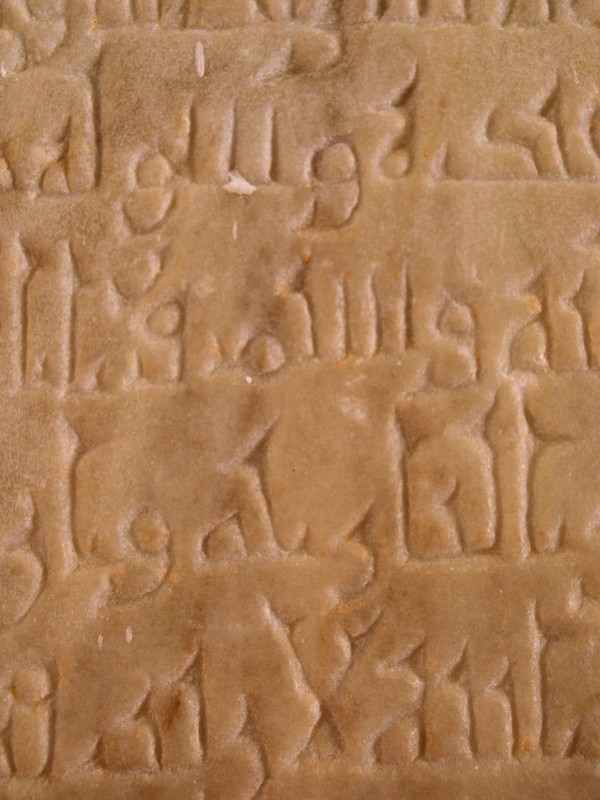

The mosque of the Three Gates

The zaouia of Sidi Abid al-Ghariani

Zawiya (زاوية), just like ribat, is essentially a Maghrebian term. The same would be called khankah in the East, tekke in Turkey, dahira in Senegal, darga in the South-East Asia, and a Sufi lodge in English. The word probably comes from the Arabic verb inzawa (to seek retirement), and this is what it is, a quiet place dedicated to religious practices. As teachings of various kinds are usually provided, the zawiya is often confounded with a madrasah, but at the core there is always a Sufi brotherhood, and often the figure of its founder, so a zawiya often is, or contain, a mazar (mausoleum) of such a personage. But there is more than this, in smaller or a larger scale: a mosque, a room for teaching, often also rooms offering an accommodation to travellers or the needy. There is often a habous, or a pious foundation, destined to the maintenance of such a place.

This particular zawiya, built in the 14th c., bears the name of a successor of a kairouani fakih, Al-Jadidi, who died during his hajj in 1384. Abu Samir Abid al-Ghariani taught in this place for some twenty years, till his death in 1402, and was buried there. Many elements, like the marble pavement, date from the 17th c.

This particular zawiya, built in the 14th c., bears the name of a successor of a kairouani fakih, Al-Jadidi, who died during his hajj in 1384. Abu Samir Abid al-Ghariani taught in this place for some twenty years, till his death in 1402, and was buried there. Many elements, like the marble pavement, date from the 17th c.

Sousse

The ribat of Sousse

Ribāṭ (رِبَـاط), a term sometimes translated, not quite exactly, as a "fortified monastery", is a peculiar Saharan construction. I'm not sure if it exists in any other part of the Islamic world. It served as a protection of frontiers or trade routes. But there is also a type of maritime ribat, I'm not sure of connected with the idea of defence against pirates, or simply for the sake of ascetic life. Calling anything a "monastery", in Islam, is obviously improper, but those who decided to dedicate their lives to the holy war or to ascetism also used to perform certain communal rituals. It is also possible to see the ribats as centres of knowledge, or at least of transmission of a determined kind of ideologies. This is the reason why this type of quadrangular construction, with individual cells inhabited by those dedicated to the cause of God, became the model of many madrasahs of the North Africa - that nonetheless usually distinguish themselves by far more ornate style.

The ribat of Sousse is the most ancient in Tunisia, competing with that of Monastir (whose present form dates from the 10th c.). It is an 8th century construction, destroyed, re-erected and expanded by the Aghlabid emir Ziyadat Allah I in 821. By the way, it stands on an even older, Byzantine foundation, and it contains columns with Corinthian capitals; they may have been recovered from that original Byzantine building on the site, or belong to the plunder from the Byzantine city of Melite on Malta, brought to the ribat in 870.

The ribat of Sousse is the most ancient in Tunisia, competing with that of Monastir (whose present form dates from the 10th c.). It is an 8th century construction, destroyed, re-erected and expanded by the Aghlabid emir Ziyadat Allah I in 821. By the way, it stands on an even older, Byzantine foundation, and it contains columns with Corinthian capitals; they may have been recovered from that original Byzantine building on the site, or belong to the plunder from the Byzantine city of Melite on Malta, brought to the ribat in 870.