|

Vertical Divider

|

Sine nobilitateThere is certainly a great lifestyle crisis at the moment of my moving to the Netherlands. I ask myself to what degree I should abandon a certain rough and casual lifestyle of my Polish years, and what kind of new social and academic image I should adopt. The question is not as trivial as it might seem. It is not just the question of wearing jackets; it is intimately connected to the quality and style of my writing, academic output, the sort of figure with which I come to my new academia.

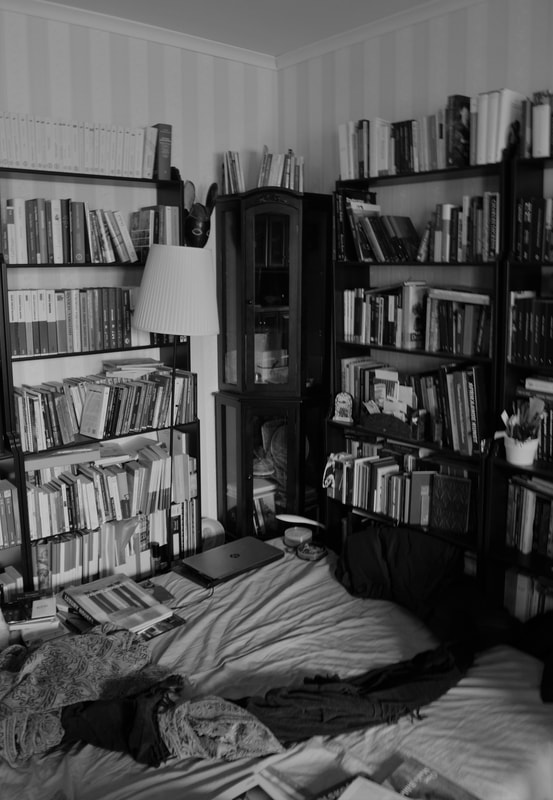

I'm not sure if it is so very well known where the word "snob" comes from. In fact, it has quite a decent origin: the abbreviation standing for the Latin sine nobilitate in the registers of students at Oxford University. And that is in fact my case, as I shamelessly reveal in The Four Riders. Consequently, I believe there is a particular s.nob. lifestyle, irreducible to the ways of those born cum nobilitate. Being a s.nob. requires a lot of additional effort, this is why it is, first of all, a lifestyle based on distinctive work habits, toughness, and a specific sort of symbolic creativity that permits to jump across social barriers that has been carefully built up and maintained, after all, to be respected. As long as I was in Poland, a certain roughness was a must; after all, my university earnings were just a little above one thousand euro, which equals the economic level of a simple worker in Western Europe. As I was going abroad for conferences, usually I was reserving just a berth in a hostel dormitory; single room has never been an obvious standard. Minor as it might be, it was one of the factors of my decision of resigning from my post at the University of Warsaw. Certainly, the institution was covering my research activities. As associate professor, I was receiving extra money, as much or even more than other colleagues; but also my activities were more frequent and complex than those of other people. My research budget represented some two thousand euro a year, out of which I often had to pay the publication of my books, as well as collective volumes I was editing (sic!). This is why cheap buses across Europe and common dormitories were entering massively in the balance of my research accounts. And dormitories were OK for many years; I saw myself as a traveller, an adventurer; I never gave much importance to my identity as a university professor. But at a given moment I would become a silver-haired woman, and then what? Common rooms are decent as long as you are young; they become indecent when you are old. The first reason why I decided to include this Lifestyle page in my website was the thought of my PhD students and younger colleagues. Many of them, unfortunately, were under the impression that an academic career, implying that they are "the best" and form some sort of "elite", would give them a corresponding material stance. In many cases, these aspirations were boosted by the families, especially the ones who had no academic history in the past; the familiar environment of those young researchers often increased their frustrations by fostering unrealistic expectations and various "must have": if a son, a grandson, a brother or a cousin achieved such an unheard-of status as a university man, they expected to see him surrounded by equally unheard-of elegance and splendour. And were often quick to conclude that all the supposed academic status was nothing but a lie, and the person in question was just nobody, nobody at all. On the other hand, the PhD students had their own illusions as well. They naively believed, for instance, to be able to rise a family with their doctoral stipends. Certainly, such ambitions are but natural at their age; nonetheless, such situations led to multiple frustrations. On various occasions, privately, I tried to explain them that I never had such aspirations. In Kraków, I was glad to live in a studio of less than 40 sq. meters; far below the level of how my PhD students imagined their homes. Since my young age, I was prepared for a much tougher life, and this is how I managed to find my equilibrium all along my own academic path. But such pieces of information were usually coming too late to the awareness of my PhD students, and served only to increase their anger. Or to dismiss me as some pitiful loser. Meanwhile, it is nothing but the crude reality that the lifestyle based on scholarship, intellectual work and creative development is not a piece of white bread, especially for those who come from underprivileged families in Eastern Europe. On the other hand, there is a long history behind the association between scholarship and luxury or social distinction; there is no way of denying it. And in my particular biographical situation, this tradition might eventually be much more in the way of a problematic burden than just the necessity of putting up with the smell of common dormitories. Many of my Polish colleagues were working in two or three universities at the same time, just to grant themselves the "professorial" lifestyle they expected - and, as I've suggested above, those around them expected. I preferred to grant myself a fully professorial competence, even if I knew that ignorance and competence are the least conspicuous parts of those social battles for prestige. At least in Eastern Europe. But now that chapter in my life is closed, and a new challenge arises, in a context where people start up from a lot of accumulated capital, both material and symbolic. The tradition of scholarly discipline, that one may qualify, after Agamben, as a "forma di vita", dates back from the Renaissance, at least for what concerns its most pronounced lifestyle features. That's 444 years, just as the lifetime counter of this particular university indicates. Arguably, it may also be seen as an even older heritage: medieval, late antique, Greek. Or Andalusian, Islamic, Chinese. Be that as it may, the heritage of scholarly elegance and distinction is something that requires the adoption of an attitude. At those 444 years of age, Leiden looks like a garden; professorial apartments are ready for visual inspection through their extra-large window panes, exhibiting a profusion of books, paintings, pianos, African curios, chandeliers, reading armchairs, paraphernalia. Certainly, even in Poland, I had some well-defined lifestyle aspirations, as well as things, material possessions of which I was proud; I had no such parterre window as my Dutch colleagues have, but I had - not to search very far - this website, which is a bit of a display vitrine as well. Obviously, the most conspicuous element were my travels and in general, whatever might be qualified as my participation in the world. I also gathered my little set of paraphernalia. Let me speak of them, first books, and then all the remaining attributes and symbols of my scholarly status. Multilingual LibraryBeing a scholar starts in a library, and possessing a library, although it is not such an obvious working condition as it might seem (the actual work is always based on much bigger sets of materials than any private person might possibly gather, such as national libraries or those belonging to leading universities), is the first element of scholarly pride and display.

Great profusion of books, usually dishevelled and stored in such a chaos as would suggest intense and uncontrolled perusal, was the intelligentsia's status symbol in the communist Poland. Also a symbol of resistance and fidelity to higher values. On the other hand, even as a child, I was enough of a keen observer to see that those private libraries were the very image of our material and intellectual poverty. No wonder that in the late 1990s and early 2000s some people got rid of such stuff, and once or twice I was invited to a flat inhabited by a couple of university professors in which I could not see a single bookshelf. In my Four Riders, I also commented on the schizophrenic attitude of Polish intelligentsia towards books, that were usually stored, preserved, treated as a lofty symbol, but not necessarily read. When they ceased to be the symbol, as I've said, of resistance and fidelity to higher values, they simply disappeared. When I started to collect books as a child, I was obviously influenced by those habits and usages of the society around me. We had practically no books at home, except some manuals or the ones my mother received from her intelligentsia friends or colleagues. But the social world around me was dominated by intelligentsia values. One of them was the absolute necessity of having books. It was a sort of sacred and sanctifying possession that everyone should have (especially the books containing Romantic poetry). We had neither a Bible nor Pan Tadeusz at home; my first mission, as a child, was to acquire a set of three volumes of Adam Mickiewicz's poetry; anyone who wished to get it had to provide a determined amount of old, recyclable paper, and I sacrificed all my school notebooks. But Mickiewicz's books were not mine; they occupied the place of honour in the main room of our home. The first book of my own was quite different, it was an atlas of birds of Europe, a rare luxury at the time that I possess till the present day. I also had some smaller, children's books about nature. But the true scholarly collection started with my early interest in humanities. Obviously, I could gather only such books as were available in Poland across those historically difficult decades. Since the very beginning, my little library was characterised by its unsystematic character; I often had - and have to the present day - books that other people did not wish to possess, the books that remained homeless. Often because their content was so exotic that no one wanted them. On the occasion of my travel to Kraków in April 2019, I threw away quite a memorable little book, number 001 in the first attempt at cataloguing my bookish possessions. It was a popular presentation of Indian mythology, written by a couple of Polish authors; by "Indian mythology" they meant a summary description of various deities and holy figures of Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism. Of course, that miserable book, illustrated with blurry black-and-white photos of Indian sculptures, and also written in a chaotic, incompetent way, was a sad souvenir, and finally I decided to get rid of it. Yet I've read it all over before throwing it to the recycling bin, meditating on the destiny of my remaining Polish books, bearing a dubious sentimental value, and otherwise worthless. It is nonetheless very hard to part with them. Perhaps this is why I write this text here. Right about the time when I started collecting books, a curious cultural change took place. In the late 1970s, a new appetite for the world haunted our closed society; travelling abroad was largely excluded for both ideological and financial reasons; reading about the world was an obvious ersatz. In a way, I am a product of that time. My Indian mythology was a part of an editorial series with the ambition of covering all the ancient civilisations of the world; I could have only this single volume, but I borrowed most of the remaining ones from public libraries. There was also an enormous series published by Ossolineum, gathering critical editions of world literature; later on, I managed to gather quite a lot of them. On the other hand, the prestigious Bibliotheca Mundi, offering volumes containing Polish translations of such texts as Shahnameh and Roman de la Rose in elegant, dark green canvas hardcovers, was beyond my reach. I had no money to buy books systematically, and also it was not easy; books, like everything else at the time, were in short supply. This situation changed only after the change of the regime. In the early 1990s, soon after the democratic transition, new books became available. It was a time when everybody wanted to learn English, and even a dishevelled pocket edition of such a book as Orwell's 1984 was seen as a valuable possession. I had one, full of loose pages; it must have passed through many hands before it reached mine; I finally threw it away in 2016, in Lisbon, after it accompanied me for the last time on my journey. On the other hand, new editing houses were proliferating, trying to provide the avid readers of the time with all those things that were not available in the communist Poland: humanities, erotica, foreign novels. Pity that the horizons of those editors remained shaped, in a way or another, by the formed period. We were still reading Mircea Eliade and all the comparative religions stuff, completely missing postcolonial studies and other such currents that would imply too much of a mental revolution for us. We were desperately conservative, avid of classics we never had before, avid of classicists and traditionalists such as Kerényi. I still have all those Orphic mysteries of the time; most probably I will remain sentimentally attached to them for the rest of my life. In a sense, they were my roots, my beginnings, the first definition of what scholarship is that ever appeared on my horizon. My little book collection acquired its status of a Multilingual Library already in the 1990s, after 1993 to be exact, when I started travelling to France, Portugal, Spain and Italy. I could gladly make economies on food to buy books at that time, and I brought a fair few. Nonetheless, they were still very miserable editions, such as Tascabili Newton a due milla lire that marked that period in Italy. Western Europe, especially the southern fringe of it, was not always rich in books as it is now. It makes a part of our common history. Be that as it may, I start to be vaguely ashamed of possessing (yes, I still do) those brittle volumes a due milla lire, that were certainly not designed to last for so long. In spite of those early acquisitions, my library achieved a substantial size only in the 2010s. I bought my Cracovian apartment in 2004, and it it took several years to fill it with books, till the moment when the limited surface became occupied to its full capacity. What I find particularly annoying is that our Polish flats used to be very low; the ceiling is at 2,5 meter. When I moved to the West, I appreciated quite especially the fact that rooms are often so tall; in Poland, they would be considered too hard to heat. It became one of my dearest and direst desires to possess one day a set of solid mahogany bookcases up to the ceiling, with a movable ladder attached to it. That would be great to keep all my books. My Cracovian apartment, stylistically speaking, was (still is) a rather woeful middle step between poverty and aspiration. My first basic furniture (bed, table, chairs) was provided by East European IKEA (which is not exactly the same IKEA that exists in the West); the bookshelves were even less than this; I made them myself with spare boards. I was painting them in the balcony at the precise moment Poland joined the European Union. No wonder that I started hating that make-shift furniture as early as 2007. At that moment, I was already an associate professor at the country's leading university, and I decided to fill my apartment with a becoming furniture, that I see today as a sort of cheap bourgeoisie imitation. But at least visually, it provided that sense of "decent" and "becoming" that I needed at the time. People from my family never had anything of the kind, let alone better than that. And certainly it was very similar to the things I might eventually see in my colleagues' apartments. At the moment it was just enough to fulfil my aspirations. That was the conformist episode in my lifestyle history; the flowery wallpaper that still remains in my Cracovian apartment is the testimony of that stage. Yet soon my stylistic evolution took me to other, less conventional spheres. A new lease of travels that started more or less in 2009 led me not just across the Romance Europe, but this time also toward the Mediterranean, Maghreb and the Middle East. Which implies, of course, not only new book acquisitions, but also the exposition to quite a new range of styles. After my various stays in Lisbon and the travel to West Africa in 2016-2017, the bourgeois wallpaper entered in a strange contrast with several African masks. Meanwhile, travelling, I had no time and no spare means to redecorate my apartment; also the deterioration of social and political climate suggested that I might be obliged to abandon it soon. I hope that, at this moment, it becomes clear to the Reader how intimately such spheres as intellectual maturation, travels, private library, furniture and wallpaper are connected. From my travels, I started to bring souvenirs and curios as well as books, and books in a growing range of languages. By the mid-2010s, a new lease of my poliglottism appeared, bringing new aspirations of diversifying my library also in terms of languages in which the books were written. I never went as far as collecting multilingual books for their own sake (i.e. books I would be definitely unable to read); essentially, I refuse myself to do this. Those new acquisitions were connected with the discovery that I might be able to cope with texts written in quite a wide range of languages. As I try to make an inventory of them right now, I can say that my Multilingual library contains books in such tongues as: Polish, English, German, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, Catalan, French, Italian, Romanian, Russian, Ukrainian, Czech, Slovenian, Croatian, Arabic, Maltese. Ah, and there is also a Septuagint, some texts in colonial Latin (Clavis Prophetarum, by the Portuguese Jesuit priest António Vieira), and such things as bilingual editions in Portuguese and Kriol of Guinea-Bissau. A good edition of Occitan poetry is still an important omission, but somehow I never had an occasion to acquire it. Only a small fraction of my books correspond to planned, well chosen or systematic acquisitions. Most of them have been bought occasionally, at reduced price, or just received, often under more or less anecdotal circumstances. The story of my Septuagint might be illustrative. I received it many years ago from a Catholic priest from the theological academy in Kraków who required my service as an examiner in Portuguese language. At the time, I was a young, idealistic assistant professor of the Jagiellonian University, serving gladly any member of the society who might need my skills for any purpose whatsoever. Usually for no fee. But the priest asked me how much it would be for my participation. For sure I would just come to hear his exam, with no thought of gain, but it crossed my mind that, if I need his service, for marriage, funeral, mess in my intention, or any service of the kind, he would expect something for his trouble and, for what I had heard, it might be not quite an inconsiderable fee. So I said I wanted a nice gift, an interesting Bible in Greek or Latin or Hebrew or Aramaic or any language of the kind. He asked how many Bibles he should provide. The question took me by surprise. Oh, just one, I mumbled. And this is how I ended up with my handsome Septuagint. Pity I didn't ask for the whole lot. This is how the Greek Old Testament appeared in my ecumenical collection of sacred writings, for several years standing back to back with a Damascene Qur'an that I brought from Syria before the war, a Polish tafsir by Józef Bielawski and a Saudi edition of Sirat Nabi in English. I also used to have other things, such as Czesław Miłosz's translation of the Gospels, some odd volumes of typically theological literature by classical Hanbali and Maliki scholars, as well as as an abundant, yet extremely unsystematic Sufi collection. But that was before. At a given moment, I felt somehow spurred to remove that sort of material form the central shelves in my Cracovian apartment and store it more discreetly in some cartoon boxes. Just in case. Finally, the decision of leaving Poland put a new stress on my book collection. This is when I asked myself, for the first time, several basic questions. What use do I expect to make of my books? How many should they be? What are the right and legitimate choices concerning their disposal? Of course, I have been throwing some of my books all along the way, even if it was each time just like a departure of a cherished one. I am also a regular donor of a tiny Public Library no 27 in Kraków. I used to get rid, in the first place, of popular books, feeling vaguely ashamed of possessing such things unbecoming my professorial status. Various volumes of Harry Potter (except a Ukrainian version that I'm still using in order to learn the language) and novels by Terry Pratchett went the way of those generous donations. On the other hand, I could not part with my favourite collections of Victorian ghost stories; I am a big fan of the genre. Also, I still have many books to remove for their materially miserable aspect, such as those Italian books a due milla lire; they disappear slowly, because I want to read them before I throw them (otherwise, how to justify the fact that they occupied my space for all those years?). But the great dilemma right now is what to do with all the books in Polish, such as Polish translations of literature that I'm able to read in the original. I think about it as I spend my idle time making a catalogue of my books on Libib.com (my husband asks what is the use of it, if I have those books already on my shelf; but somehow the app helps me to contemplate my collection critically, control it, grasp the objectives, character and limitations of it). Overall, my Multilingual Library contains right now approximately 2 000 books. That size represents enough reading for several years to come (to enjoy reading one book every weekend, we barely need some 50 books a year; to read one roughly every three days, we would need as many as 100 or 120 a year; thus, my 2 000 books represent a reasonable provision for nearly twenty years). The question is whether I want to keep it this size, or to expand it in the future. What the ideal size would be? I often think about 10 000 books (which would be about 10% more than the famous theosophic library that once belonged to Rudolf Steiner, and more than is possible to read in a human lifetime; I would also need to make some research in the meanwhile, and my strictly academic books only partially overlap the private collection; they would be brought from the University Library and return there in more or less constant circulation). Most probably, I could collect it very easily, if I work in the Netherlands and achieve a decent status; the shelves would be probably the most cumbersome investment. The question is why, for what purpose. Display? Ostentation? Enjoying their sheer presence? Greed? Inability of restraining myself? It may not be reasonable, but somehow the idea of mahogany bookcases, movable ladder and 10 000 books sticks to my mind. And the day in which I might sit in my armchair to meditate nostalgically on those times when I left Poland with a suitcase and a library of barely 2 000 books in only 19 or 20 tongues. Here I come to the most interesting, and at the same time difficult aspect: the leading idea of my collection. As I've said, to acquire or scavenge 10 000 books may take shorter time than expected, especially as I am in the Netherlands, where people simply leave for each other the good books they don't want any longer. It puts in the limelight the necessity of a criterion. Since the very beginning, the idea of my library was that of Bibliotheca Mundi, derived, perhaps, from those unfulfilled universalist aspirations that Polish intelligentsia might have nurtured at a given moment of her historical trajectory. I wanted to create a private representation of the world and world literature (on my bookshelves as well as in my writings); the complexity of such an endeavour would justify the size of the envisioned collection, even if I would be unable to read extensively all my books. A globe (that I acquired in Warsaw some time around 2014 or 2015) was an essential element of the unavoidable paraphernalia; African masks were completing the scene. I like to buy my books (as well as read them, and occasionally destroy) in travel. It is on the move that books actually acquire the strongest taste, they gain from the inscription in a real world. Materially, this is how I would like to organise my ideal library, by geographical and cultural areas, like a metaphorical map, or a mandala of the world. As I said, currently there are many common books of little value in my possession, and I never considered them as unworthy of my attention for this reason. Yet if I see my possibilities increase in the future, the rare and expensive books I would like to acquire are of the worldly kind; I want to seek them in the places where they are born, and to follow the emergent narrations of the world: those of the desert, various deserts. Those of the Fulani world, and of Central Asia. Those of various Bedouins, that seem to be in vogue right now; such a vogue that would probably never reach my old country (although I wrote an incomprehensible essay on it in Polish, EREGNAT EM ILON; I wonder if it ends up published). These are fashions that appear only in very peculiar, sophisticated circles: here, in Oxford, in a few other places like that. Strangely, they constitute perhaps the only fashion that I feel attracted to, the only lifestyle trends for which I would be ready to surrender my comfort. And this is also how I plan to complete my journey, reaching the academic top of the planet, and settling in it for the reminder of my life, just like some pious Muslims used to settle in Mecca at the end of their hajj. Books to come and making things to lastCurrently I live in a sort of extravagant loft in Leiden, occupying a studio on the top of a neo-Gothic building that in its time (1898) used to be some sort of advanced laboratory belonging to the Faculty of Pharmacy. Now it serves to host some international students and minor guests of the University. As I wait for new research money to come, I meditate on what I would like my lifestyle to be in the future. For sure, I will become much more sober. The flowery pattern of my Cracovian wallpaper must go, although I'm still attached to gold as a colour. It is an art historian's, not a snob's fascination. Golden backgrounds have been the visible sign of transcendence for too many centuries, and I actually plan to paint at least some sections of my walls in gold. The rest, I suppose, will be in a light ivory tone that fits the Dutch standards of cleanness, transparency and luminosity.

If I manage to get sufficient means for this, I'm planning to buy one of those typical houses, with its large windows, a parterre saloon open to visual penetration from the street, and a discreet bedroom upstairs. I will need several silk lined curtains, as they often make the splendour of elegant Dutch homes. The space in front, as narrow as it can be, should be occupied by a rose garden, with climbing stems on each side of the entrance door; the same, with even more spiritual meaning, at the back, if only there is enough sun to keep the rose bushes in good condition. I'm sensitive to the charm of wisteria, but I observed that for some reason their blossom stays for a very short time here, shorter than in France; on the other hand, gulistan has the cultural connotation that fits the Orientalist dominant of my life in Leiden; I also add a Persian carpet and a provision of Eastern pottery with metallic glaze to the list of my projected acquisitions. Other flowers, such as tulips in the spring and peonies in the summer, will be bought every week and used to decorate the interior. The 10.000 volumes of my projected library are to occupy, as I calculate, a high room, about 6 meters long, filled with well designed bookshelves. It is the wall behind them that I plan to paint in lustrous gold, the sign of transcendence to appear every time that a book is removed from its place. I'm not sure if I will ever be able to get more than this; a home with just two spaces (this library downstairs and a little bedroom upstairs) is as far as my aspirations go. But if one day I could have more than this, I would split the library into separate cultural areas, accompanied by their corresponding collections, so the Persian carpets, Islamic calligraphy and glazed ceramic don't mix up with African sculpture or reindeer skins. Finally, I should start more systematic acquisitions. As I said, I'm attached to the serendipitous aspect of this library as it is supposed to be a sort of reflection of the world, and I will bring a lot from my travels. On the other hand, I would like to make its Mediterranean and Oriental section as complete as possible. In particular, I would like to collect the poetry between al-Andalus, the Romance troubadours and the Sicilian school. The global aspect of my library should go beyond the most common sort of postcolonial novels, perhaps toward ethnological materials. There would be plenty of art books, photography books. My egotistic feelings are excited by the thought that I would also leave something in a guise of a Nachlass. Apparently, the term ceased to have any meaning nowadays, when whatever we write is stored on a single pendrive. No more romantic vision of burning manuscripts in a fireplace; I just threw an armful of papers into the recycling bin at the end of my stay in France. But there should be a Nachlass, something specific that I leave behind. These things are very fragile, I know, and sort of inoperative. Lonely people lacking attachments, just like me, should take a good care to say whatever they wish to say in their lifetime, because no one will come to search for their writings when they are no more, and it is not realistic even to think about any such possibility. This is why I've taken a specific care to publish all my Polish writings before leaving Poland. But perhaps the prospect of making my life in Leiden opens quite a new perspective. Somehow. Or a new illusion of continuity, of belonging, of posterity. The thought, in any case, is of making things to last. This is, in a way, the very essence of the Low Countries. Perhaps it is for this reason that I came here. |

- Home

-

RESEARCH ARCHIVE

- ALL TEXTS

- COMPARATIVE LITERATURE

- CULTURAL THEORY & CULTURAL ANALYSIS

- GLOBAL LITERARY STUDIES >

- GLOBAL HISTORY OF IDEAS

- APOCALYPTIC STUDIES

- ARAB LITERATURE

- ASIAN STUDIES

- EAST EUROPEAN & POST-SOVIET STUDIES

- EROTICISM & SEXUALITY STUDIES

- EURO-MEDITERRANEAN WRITING >

- FEMINISMS, GENDER & QUEER STUDIES

- ISLAMICATE INTELLECTUAL HISTORY

- LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES

- LUSOPHONE AFRICAN STUDIES

- MAGHREBIAN & WEST AFRICAN STUDIES >

- MARITIME HUMANITIES

- PLANT & ANIMAL STUDIES >

- PORTUGUESE STUDIES >

- GLOBAL MEDIEVAL & EARLY-MODERN STUDIES >

- SUFI LITERATURE

- TRANSCOLONIAL & TRANSINDIGENOUS STUDIES

- TRAVEL WRITING >

- GLOBAL 19TH-CENTURY STUDIES

- GLOBAL MODERNISMS

- WRITINGS ON ART

- EXPERIMENTS

-

THE WORLD

- ARCTIC & SCANDINAVIA >

- EASTERN EUROPE >

- WESTERN EUROPE >

- THE BALKANS >

- CAUCASUS >

- MIDDLE EAST >

- MAGHREB & SAHEL >

- WEST AFRICA >

- THE HORN OF AFRICA >

- THE SOUTH OF AFRICA >

- INDIA & INDIAN OCEAN >

- SOUTH EAST ASIA >

- IRAN & CENTRAL ASIA >

- NORTH & NORTH EAST ASIA >

- NORTH AMERICA >

- MESOAMERICA >

- THE CARIBBEAN >

- SOUTH AMERICA >

- POLYNESIA >

- MICRONESIA >

- MELANESIA >

- AUSTRALASIA >

- ANTARCTICA >

- MARGINALIA

- ABOUT & CONTACT