what is Armenian literature?

Armenian intellectual tradition is deeply rooted in the first centuries of Christianity. Curiously, Armenia was the first Christian state, even before the conversion of Constantine. Later on, there was a mind-boggling experience of Armenian traders, such as those who brought the silk tissues from Isfahan to almost all of the early-modern world. The study of the phenomenon, contributing to early-modern globalization, is under scrutiny of such scholars as Sebouh Aslanian. Extensive literacy must have been connected to such a collective experience, yet this is still an open research topic.

The origin and early history of Armenian literature as it is usually understood can be traced back to the early Christian period, with the invention of the Armenian alphabet in the 5th century. This significant development is credited to Saint Mesrop Mashtots, who, along with his collaborators, created the script in 405 AD. But at the moment of the country's conversion to Christianity, Armenia was already an ancient land. The region was home to the Urartian Kingdom, an ancient civilization that flourished from the 9th to the 6th centuries BCE, known for its advanced architecture, including fortresses and irrigation systems. In the 6th century BCE, Armenia came under the influence of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. After the conquests of Alexander the Great, the region experienced Hellenistic influence. Artaxias I, a local satrap, established the Artaxiad Dynasty in 190 BCE, marking the beginning of the independent Kingdom of Armenia. Between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE, Armenia became a buffer state between the Roman Empire and the Parthian Empire, leading to a series of power struggles. The Treaty of Rhandeia in 63 CE established a fragile peace, dividing Armenia into Roman and Parthian spheres of influence. Finally, at the beginning of the 4th century, the conversion to Christianity marked a crucial turning point. Tradition holds that Gregory the Illuminator converted King Tiridates III and the Armenian people to Christianity around 301–314 CE, making Armenia the first nation to officially adopt Christianity as the state religion.

Prior to the creation of the Armenian alphabet, Armenian literature was primarily oral, transmitted through storytelling and religious teachings. The adoption of the alphabet played a crucial role in preserving and promoting Armenian culture, as it allowed for the written documentation of religious texts, historical accounts, and literary works. One of the earliest Armenian literary figures is Saint Sahak Partev, who, along with Saint Mesrop, played a key role in translating the Bible into Armenian. This translation, known as the "Armenian Bible" or the "Holy Scriptures," became a cornerstone of Armenian literature and culture. The translation process began in the early 5th century and was completed around 434 AD.

During the Golden Age of Armenian literature, which spanned the 5th to 7th centuries, there was a flourishing of religious, historical, and philosophical writings. Prominent literary figures of this period include Movses Khorenatsi, who wrote "History of Armenia," and Agathangelos, the author of "The History of the Armenians." The cultural heyday should not be seen as a period of undisturbed peace. Armenia continued to face geopolitical challenges. The Sassanian Persians and the Byzantine Empire vied for control over the region, leading to conflicts and territorial shifts. Later on, Armenia experienced invasions by Arab forces in the 7th century and later faced the Seljuk Turks in the 11th century, yet the impact of Islamisation seems minimal.

Armenian writing in itself became a stronhold of identity, contributing to the fact that the country maintained its distinct cultural and religious identity. Literature continued to evolve and expand over the centuries, with various literary genres emerging. The Middle Ages saw the development of secular literature, including epic poems such as "David of Sassoun." During the 9th to 11th centuries, Anania Shirakatsi made significant contributions to scientific and philosophical literature. The later medieval period also saw the emergence of love poetry, sometimes pointing out to the existence of Armenian "troubadours", which is obviously a twist of the term out of its original scope.

Sasuntsi Davit, the epic poem dedicated to David, or the "Daredevils of Sassoun", deserves a particular attention. David is a typical epic hero, yet also the place is very important. The story is set in the historical region of Sassoun, located in present-day southeastern Turkey. Sassoun has been a symbol of Armenian resistance and resilience throughout history. The epic has its roots in an ancient oral tradition, with various versions of the story being passed down through generations by bards and storytellers. Just like the Greek Illiad, it is not the work of a single author and just like in the Greek case, the oral tradition predates the invention of script. David's exploits include battles against mythical creatures, giants, and various enemies threatening the community; he is a figure of undefatigable defensor and bringer of justice, characterised by extraordinary strength and bravery, While David is celebrated for his physical strength and martial prowess in facing mythical creatures and enemies, the epic also explores the moral dilemmas and ethical choices he encounters throughout his journey. These challenges may include decisions related to justice, loyalty, sacrifice, and the well-being of his people. The narrative often delves into the complexities of heroism by presenting David with situations that require more than just physical might. For example, David might be faced with decisions that involve balancing the demands of justice with mercy, navigating conflicts within his community, or making personal sacrifices for the greater good. These moral and ethical dimensions add depth to the character of David, elevating him beyond a one-dimensional warrior to a hero who grapples with the complexities of human condition.

Anania Shirakatsi, also known as Ananias of Shirak, is quite a different figure. He was a prominent Armenian scholar active at the time of early Islamic expansion. He was a mathematician, geographer, and astronomer who lived during the 7th century. His contributions encompass a wide range of fields, and he played a significant role in advancing knowledge in medieval Armenia. His best known work, titled "Ashkharatsuyts" (The World), was completed around 670 CE. This geographical treatise provided a comprehensive overview of the known world, launching the foundation for a nation of traders and early globalizers.

During the period that goes from the 11th to 14th century, Armenia expanded beyond what is today the country's territory. It was the time of the establishment of various Armenian kingdoms and principalities, such as the Kingdom of Cilicia. During this time, Armenian literature flourished, producing a wealth of religious, historical, and philosophical works. Notable figures include Matthew of Edessa, who wrote a chronicle covering the period from the creation of the world to the year 1136, and Nerses Shnorhali, a Catholicos and influential poet. There was a notable increase in secular literature, including love poetry and epic narratives. The "Yerevani Zhoghovrdakan Grogh" (Yerevan Book of Fridays) is an example of secular poetry that reflects the influence of Persian and Arabic literary traditions.

Among medieval and early modern Armenian masterpieces, we may quote Grigor Narekatsi's "Book of Lamentations" (or "Lamentations of Narek"), a deeply spiritual and poetic, late-10th-century work that has been considered a pinnacle of Armenian mystical literature. Almost on the antipodes, Mkhitar Gosh was a scholar, historian, and legal expert who created "Datastanagirk" (The Book of Law), a legal code that played a crucial role in Armenian jurisprudence.

Like many ancient nations (see the paradigmatic example of the Jews), Armenians suffered an exodus and a partial break of continuity, becoming a diaspora. We can see them back in the 17th and 18th centuries, marked by a period known as the Armenian Enlightenment. This era saw a revival of interest in classical Armenian literature, the establishment of printing presses, and the publication of numerous works. Notable literary figures from this period include Awetik Issahakian and Sayat-Nova. Nonetheless, it was, for all the Caucasus, the moment of clash with Russia. As in other places, it was devastating, but also had a cultural impact. The 19th century witnessed a national and cultural revival. Khachatur Abovian played a key role in shaping Armenian modernity as he authored the country's first novel, "Wounds of Armenia". The 20th century, still in the shadow of Russia, brought diverse literary movements and styles. Figures like Hovhannes Tumanyan and Yeghishe Charents made significant contributions. The Armenian diaspora also produced notable writers, such as William Saroyan.

The origin and early history of Armenian literature as it is usually understood can be traced back to the early Christian period, with the invention of the Armenian alphabet in the 5th century. This significant development is credited to Saint Mesrop Mashtots, who, along with his collaborators, created the script in 405 AD. But at the moment of the country's conversion to Christianity, Armenia was already an ancient land. The region was home to the Urartian Kingdom, an ancient civilization that flourished from the 9th to the 6th centuries BCE, known for its advanced architecture, including fortresses and irrigation systems. In the 6th century BCE, Armenia came under the influence of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. After the conquests of Alexander the Great, the region experienced Hellenistic influence. Artaxias I, a local satrap, established the Artaxiad Dynasty in 190 BCE, marking the beginning of the independent Kingdom of Armenia. Between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE, Armenia became a buffer state between the Roman Empire and the Parthian Empire, leading to a series of power struggles. The Treaty of Rhandeia in 63 CE established a fragile peace, dividing Armenia into Roman and Parthian spheres of influence. Finally, at the beginning of the 4th century, the conversion to Christianity marked a crucial turning point. Tradition holds that Gregory the Illuminator converted King Tiridates III and the Armenian people to Christianity around 301–314 CE, making Armenia the first nation to officially adopt Christianity as the state religion.

Prior to the creation of the Armenian alphabet, Armenian literature was primarily oral, transmitted through storytelling and religious teachings. The adoption of the alphabet played a crucial role in preserving and promoting Armenian culture, as it allowed for the written documentation of religious texts, historical accounts, and literary works. One of the earliest Armenian literary figures is Saint Sahak Partev, who, along with Saint Mesrop, played a key role in translating the Bible into Armenian. This translation, known as the "Armenian Bible" or the "Holy Scriptures," became a cornerstone of Armenian literature and culture. The translation process began in the early 5th century and was completed around 434 AD.

During the Golden Age of Armenian literature, which spanned the 5th to 7th centuries, there was a flourishing of religious, historical, and philosophical writings. Prominent literary figures of this period include Movses Khorenatsi, who wrote "History of Armenia," and Agathangelos, the author of "The History of the Armenians." The cultural heyday should not be seen as a period of undisturbed peace. Armenia continued to face geopolitical challenges. The Sassanian Persians and the Byzantine Empire vied for control over the region, leading to conflicts and territorial shifts. Later on, Armenia experienced invasions by Arab forces in the 7th century and later faced the Seljuk Turks in the 11th century, yet the impact of Islamisation seems minimal.

Armenian writing in itself became a stronhold of identity, contributing to the fact that the country maintained its distinct cultural and religious identity. Literature continued to evolve and expand over the centuries, with various literary genres emerging. The Middle Ages saw the development of secular literature, including epic poems such as "David of Sassoun." During the 9th to 11th centuries, Anania Shirakatsi made significant contributions to scientific and philosophical literature. The later medieval period also saw the emergence of love poetry, sometimes pointing out to the existence of Armenian "troubadours", which is obviously a twist of the term out of its original scope.

Sasuntsi Davit, the epic poem dedicated to David, or the "Daredevils of Sassoun", deserves a particular attention. David is a typical epic hero, yet also the place is very important. The story is set in the historical region of Sassoun, located in present-day southeastern Turkey. Sassoun has been a symbol of Armenian resistance and resilience throughout history. The epic has its roots in an ancient oral tradition, with various versions of the story being passed down through generations by bards and storytellers. Just like the Greek Illiad, it is not the work of a single author and just like in the Greek case, the oral tradition predates the invention of script. David's exploits include battles against mythical creatures, giants, and various enemies threatening the community; he is a figure of undefatigable defensor and bringer of justice, characterised by extraordinary strength and bravery, While David is celebrated for his physical strength and martial prowess in facing mythical creatures and enemies, the epic also explores the moral dilemmas and ethical choices he encounters throughout his journey. These challenges may include decisions related to justice, loyalty, sacrifice, and the well-being of his people. The narrative often delves into the complexities of heroism by presenting David with situations that require more than just physical might. For example, David might be faced with decisions that involve balancing the demands of justice with mercy, navigating conflicts within his community, or making personal sacrifices for the greater good. These moral and ethical dimensions add depth to the character of David, elevating him beyond a one-dimensional warrior to a hero who grapples with the complexities of human condition.

Anania Shirakatsi, also known as Ananias of Shirak, is quite a different figure. He was a prominent Armenian scholar active at the time of early Islamic expansion. He was a mathematician, geographer, and astronomer who lived during the 7th century. His contributions encompass a wide range of fields, and he played a significant role in advancing knowledge in medieval Armenia. His best known work, titled "Ashkharatsuyts" (The World), was completed around 670 CE. This geographical treatise provided a comprehensive overview of the known world, launching the foundation for a nation of traders and early globalizers.

During the period that goes from the 11th to 14th century, Armenia expanded beyond what is today the country's territory. It was the time of the establishment of various Armenian kingdoms and principalities, such as the Kingdom of Cilicia. During this time, Armenian literature flourished, producing a wealth of religious, historical, and philosophical works. Notable figures include Matthew of Edessa, who wrote a chronicle covering the period from the creation of the world to the year 1136, and Nerses Shnorhali, a Catholicos and influential poet. There was a notable increase in secular literature, including love poetry and epic narratives. The "Yerevani Zhoghovrdakan Grogh" (Yerevan Book of Fridays) is an example of secular poetry that reflects the influence of Persian and Arabic literary traditions.

Among medieval and early modern Armenian masterpieces, we may quote Grigor Narekatsi's "Book of Lamentations" (or "Lamentations of Narek"), a deeply spiritual and poetic, late-10th-century work that has been considered a pinnacle of Armenian mystical literature. Almost on the antipodes, Mkhitar Gosh was a scholar, historian, and legal expert who created "Datastanagirk" (The Book of Law), a legal code that played a crucial role in Armenian jurisprudence.

Like many ancient nations (see the paradigmatic example of the Jews), Armenians suffered an exodus and a partial break of continuity, becoming a diaspora. We can see them back in the 17th and 18th centuries, marked by a period known as the Armenian Enlightenment. This era saw a revival of interest in classical Armenian literature, the establishment of printing presses, and the publication of numerous works. Notable literary figures from this period include Awetik Issahakian and Sayat-Nova. Nonetheless, it was, for all the Caucasus, the moment of clash with Russia. As in other places, it was devastating, but also had a cultural impact. The 19th century witnessed a national and cultural revival. Khachatur Abovian played a key role in shaping Armenian modernity as he authored the country's first novel, "Wounds of Armenia". The 20th century, still in the shadow of Russia, brought diverse literary movements and styles. Figures like Hovhannes Tumanyan and Yeghishe Charents made significant contributions. The Armenian diaspora also produced notable writers, such as William Saroyan.

I have readDeviation. Anthology of Contemporary Armenian Literature (2008)

|

Vertical Divider

|

I have written... nothing ...

|

Sevanavank

Step 3: reading the earth

The Armenian way of existence is singularly de-territorialized. Already in the Middle Ages and ever since, the Armenian world moved around, to Cilicia, to Constantinople, to Isfahan. Perhaps this is the very reason why certain landmarks, such as mount Ararat (today in Turkish territory), acquire a particular importance.

It is even hard to say when did this process of de-territorialization actually start. It seems to be anterior to the very crystallization of a territorialized Armenian state and nation. Armenians appear in Cilicia as early as the 1st century BC, in the foundational times of Tigranes the Great. The medieval Armenian Cilicia reappears as the population moves into the Byzantine Empire under the pressure of Seljuc invasions. This medieval kingdom existed for three centuries, establishing close contacts not only with the Crusaders, but also with the Italian cities interested in the Levantine trade.

New Julfa is yet another story. It was officially established as the Armenian quarter of Isfahan in 1606, but probably reflected much older presence. Be as it may, it became an early epicenter of globalization producing one of the vastest commercial networks of a modern or even post-modern type: it flourished throughout the early colonial era unsupported by any political structure, a global emporium without the underlying tissue of an empire.

Such a historical context makes the conflict in Karabah very hard to understand, specially in confrontation with apparently uninhabited vastness of these mountains. Yet fighting for land is perhaps to become one of the crucial paradoxes of the post-globalized era that these early globalizers anticipate.

It is even hard to say when did this process of de-territorialization actually start. It seems to be anterior to the very crystallization of a territorialized Armenian state and nation. Armenians appear in Cilicia as early as the 1st century BC, in the foundational times of Tigranes the Great. The medieval Armenian Cilicia reappears as the population moves into the Byzantine Empire under the pressure of Seljuc invasions. This medieval kingdom existed for three centuries, establishing close contacts not only with the Crusaders, but also with the Italian cities interested in the Levantine trade.

New Julfa is yet another story. It was officially established as the Armenian quarter of Isfahan in 1606, but probably reflected much older presence. Be as it may, it became an early epicenter of globalization producing one of the vastest commercial networks of a modern or even post-modern type: it flourished throughout the early colonial era unsupported by any political structure, a global emporium without the underlying tissue of an empire.

Such a historical context makes the conflict in Karabah very hard to understand, specially in confrontation with apparently uninhabited vastness of these mountains. Yet fighting for land is perhaps to become one of the crucial paradoxes of the post-globalized era that these early globalizers anticipate.

Zorats Karer / Carahunge

The prehistoric site of Zorats Karer, also called Carahunge, is believed to be a necropolis, as well as an astronomical observatory. The holes bored at different angles through the menhirs seem to point towards precise spots on the sky. As much as showing whatsoever, the holes produce whistling sounds on windy days. The whole area, where other findings such as petroglyphs are also located, is first of all a place of exquisite beauty, lost in the vastness of the southern Armenian landscape. The ancestral usage of burning the stubble is still very much alive, adding a primeval agrarian ritual to the timeless landmark. Yet also here the process of "becoming art" is going on. Next to the site, a blue board announces the existence of an "artlaboratory Epicenter", supposedly dedicated to land art experiments that are often taken for a mere touristic replica of the true menhirs.

Sanahin monastery

Although the exact founding date is not clear, Sanahin is believed to have been founded in the 10th century by Patriarch Hamazasp. The monastery complex was established during the prosperous era of the Kyurikian dynasty. Major construction activities took place during the 10th to 13th centuries. King Abas I is credited as its early sponsor. Later on, in the 12th century, King Kyurike II, also associated with the Kyurikian dynasty, played a role in its expansion and renovation. His patronage supported the cultural and educational activities of the monastery.

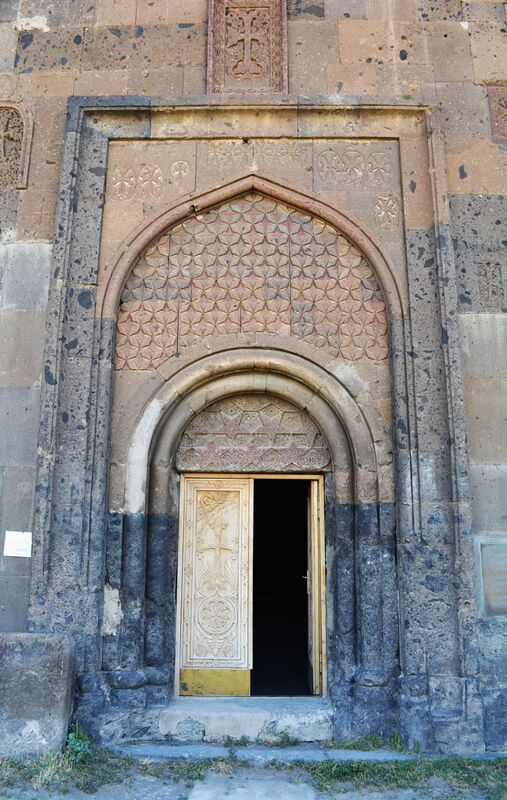

The monastery complex consists of several structures, including the main church of St. Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God), the smaller church of St. Gregory, several chapels, and a particularly photogenic gavit (narthex) that belongs to the most recognizable views not only in this complex, but in all Armenia. These buildings showcase Armenian ecclesiastical architecture with distinct features such as cross-domes and decorative carvings. The exterior and interior of the buildings are decorated with elaborate stone carvings, including biblical scenes, floral motifs, and intricate patterns.

The monastic complex is situated amidst lush greenery and integrated harmoniously with the natural landscape. The setting enhances the overall beauty and tranquility of the site recognized, along with the nearby Haghpat Monastery, as a part of UNESCO World Heritage in 1996.

The monastery complex consists of several structures, including the main church of St. Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God), the smaller church of St. Gregory, several chapels, and a particularly photogenic gavit (narthex) that belongs to the most recognizable views not only in this complex, but in all Armenia. These buildings showcase Armenian ecclesiastical architecture with distinct features such as cross-domes and decorative carvings. The exterior and interior of the buildings are decorated with elaborate stone carvings, including biblical scenes, floral motifs, and intricate patterns.

The monastic complex is situated amidst lush greenery and integrated harmoniously with the natural landscape. The setting enhances the overall beauty and tranquility of the site recognized, along with the nearby Haghpat Monastery, as a part of UNESCO World Heritage in 1996.

Grigor chapel

Saghmosavank, the "Monastery of the Psalms"

It is one of the lesser-known monastery complexes in Armenia, a less attended one, darkened with age, solitary, and neglected. It is located quite impressively near a gorge carved by the Kasagh river, providing stunning views of the surrounding landscape. The monastery was founded in the 13th century by Prince Vache Vachutian and his wife, Princess Khatun. Construction of the complex began in 1215 and continued into the early 13th century.

Saghmosavank played a significant role as a center for learning and manuscript illumination. It is often referred to as the "Monastery of the Psalms" due to its association with the transcription and illumination of psalmic manuscripts.

Strategically located on the cliffs of the Kasagh River gorge, the monastery served also as a defensive structure, reflecting the historical need for protection against invasions.

The main church of the complex is dedicated to St. Sion, It is a cruciform central-dome structure distinguished by elegant simplicity. The dome is supported by four columns, and the interior features intricate khachkars (cross-stones) and decorative carvings.

Saghmosavank played a significant role as a center for learning and manuscript illumination. It is often referred to as the "Monastery of the Psalms" due to its association with the transcription and illumination of psalmic manuscripts.

Strategically located on the cliffs of the Kasagh River gorge, the monastery served also as a defensive structure, reflecting the historical need for protection against invasions.

The main church of the complex is dedicated to St. Sion, It is a cruciform central-dome structure distinguished by elegant simplicity. The dome is supported by four columns, and the interior features intricate khachkars (cross-stones) and decorative carvings.

Selim caravanserai, 1332

This caravanserai on the Selim pass was commissioned by Prince Chesar Orbelian or his father Hasan-Jalal Orbelian to help the thence international traders on the Dvin-Partav road. The Selim pass of the Vardenyats Mountain Range was a key point on the Silk Road connecting the regions of Vayots Dzor and Gegharkunik. The Selim Caravanserai is part of a network of medieval Armenian caravanserais that served as resting places for merchants, travelers, and their animals along trade routes.

The han is a low three-nave hall with a domed chapel at the east end. Under the eastern wall, there is also a basalt watering trough for the beasts. Despite offering such basic conditions, the interior is decorated with stalactite carvings. Also, the façade is decorated, featuring a fantastic winged animal and a bull.

The han is a low three-nave hall with a domed chapel at the east end. Under the eastern wall, there is also a basalt watering trough for the beasts. Despite offering such basic conditions, the interior is decorated with stalactite carvings. Also, the façade is decorated, featuring a fantastic winged animal and a bull.