what is Egyptian literature?

Oh my goodness, yes. It's monstrous, it expands over millennia, it speaks several languages, it uses several systems of writing; there is also an oral literature in Egypt. It's mind-boggling.

First of all, we have a variety of reconstructions and (attempts at) translations of ancient Egyptian literature. Then, there is a Greek and Jewish-Greek literature in Egypt; it is in Alexandria that the Old Testament was translated into Greek (the so called Septuagint). There were numerous early Christian writers, such as Origen (although he moved later on to Caesarea and died in Lebanon). There was also an important part of classical Arabic literature that was written in Egypt. And then there is the Nahda, or the Arab modernist movement. A colonial and multicultural literature written in Egypt or related to Egypt, such as Durell's tetralogy The Alexandria Quartet (1957-1960). A modern literature both in Arabic and in colonial languages. A post-colonial Egyptian literature. A nationalistic Egyptian literature. A literature written by Egyptian diasporas.

Typically for such fertile grounds with a profusion of heritage and cultural ingredients, the Egyptian literature is fascinating, strong of flavour, picturesque. The country is one of my favourite literary destinations.

First of all, we have a variety of reconstructions and (attempts at) translations of ancient Egyptian literature. Then, there is a Greek and Jewish-Greek literature in Egypt; it is in Alexandria that the Old Testament was translated into Greek (the so called Septuagint). There were numerous early Christian writers, such as Origen (although he moved later on to Caesarea and died in Lebanon). There was also an important part of classical Arabic literature that was written in Egypt. And then there is the Nahda, or the Arab modernist movement. A colonial and multicultural literature written in Egypt or related to Egypt, such as Durell's tetralogy The Alexandria Quartet (1957-1960). A modern literature both in Arabic and in colonial languages. A post-colonial Egyptian literature. A nationalistic Egyptian literature. A literature written by Egyptian diasporas.

Typically for such fertile grounds with a profusion of heritage and cultural ingredients, the Egyptian literature is fascinating, strong of flavour, picturesque. The country is one of my favourite literary destinations.

I have readYusuf Ziedan, عزازيل | Azazeel (2009)

Ahmed Khaled Towfik, Utopia (2009) Miral al-Tahawy, الخباء | The Tent (1996) Amitav Ghosh, In an Antique Land (1992) Salwa Bakr, العربة الذهبية لا تصعد إلى السماء | The Golden Chariot (1991) Yusuf Idris, Al-Haram (1959) Naguib Mahfouz, زقاق المدق | Midaq Alley (1947), اللص والكلاب | The Thief and the Dogs (1961) Sayyid Qutb, A Child from the Village (1946) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have written |

pathos & abjection

(becoming a tourist)

kolejny epizod w barwnej biografii

("following episode in a colourful biography")

Anna Wieczorkiewicz, Apetyt turysty. O doświadczaniu świata w podróży, Kraków, Universitas, 2012, p. 44.

January 2020

It was a long postponed journey. And finally, here I am, exposed to the chilling wind of the desert that I did not quite anticipate, hiding in a group of tourists, invisible in the crowd slowly penetrating the security gates at Luxor station to catch that legendary night train to Cairo. Legendary, because I remember have read about it in any Egyptian novel.

I have read several novels before this trip, cried over Al-Haram by Yusuf Idris. Together with the great Azazeel, by Youssef Ziedan, that I had read in a French translation when I was in Tours, they make the esteem that I have of Egyptian literature. I wish I could read more, hopefully this autumn in France once again. I left my Al-Aswamy, equally a French edition, in my storage space in Leiden. Never had time enough.

On the road, nonetheless, I had something quite different to read, In an Antique Land by Amitav Ghosh, a brilliant book for the circumstance. It is a sort of mixed genre, the result of a travel made by the author as anthropologist, a young researcher collecting materials for a dissertation, penetrating deep into the human reality of Egyptian countryside; a document interwoven with autobiographic threads and historical fiction, as he tries to reconstruct, based on the documents found in Cairo's genizah, the life of a 12th c. Jewish merchant Abraham Ben Yiju, and his two slaves Ashu and Bomma, that rather surprisingly connects Egypt with his own homeland.

So, Yusuf Idris and Amitav Gosh in my pocket, this is the taste of Egypt, and the experience of that banality of being a mere tourist in an antique and dusty land, that might have some hidden connection to my own world and homeland(s).

My journey started at the airport of Hurghada; from then, through a desolate desert road, I went down to Aswan, where my cruise down the Nile were to begin. Meanwhile, I also bought an additional bus trip to Abu Simbel, at 3 am, that brought me close to pneumonia and partially spoiled my journey. Or made it more difficult, with those difficulties I rarely experienced. I was never sick on any of my travels, except for two days in Armenia, where I ate one of these traditional preserves made with condensed grape juice. The nuts inside were mouldy, and I thought this is how they were supposed to be. Of course not. The mould caused some sort of acute hypotension, and at a given moment I heard the sound of duduk very far, very far from me...

The infection in Egypt was something else, shortness of breath, the sensation of missing the air, with the access of panic that comes with it. If only I could rest, I would probably overcome it easily, but I had to move from one place to another according to a chaotic, truly Egyptian planning. With a sleepless night over another sleepless night, I got as sick as I rarely was in my life. But still, the only thing I scratched from my schedule was to enter the great Cheops pyramid; I was afraid my breath might fail me while inside. I was very weak, had to stop after climbing just a few steps, panting heavily. But even though, I penetrated all the remaining holes.

Later on, it crossed my mind that my sickness could have been an early case of COVID-19, when no one heard about the disease yet. During the charter flight back home, a man from my group fainted and was given oxygen.

So, as I said, I came by bus from Hurghada to Aswan, and then, in the middle of the night, by bus to Abu Simbel, for an early morning visit of the temple. And then I spent three nights on the Nile cruiser, enjoying food, and drinks, and all sort of luxuries available to European working classes. Those cruisers were so numerous on the river that they could not reach the piers directly; several of them were attached in parallel to the quay, and the ant lines of tourists were guided across two or three or four of them till they could reach their own. When the tourists moved in the opposite direction, for their sessions of mass sightseeing, lines of hansom cabs drawn by miserable horses were waiting to take them to the main attractions, the temples I had read about as a child.

Everything was like a fairy tale nonetheless, and still quite evocative of the classical Grand Tours of the 19th century. I wandered through the Valley of the Kings after an unforgettable balloon flight and a sunrise on the Nile. Later on, as I've mentioned, I caught the night train to Cairo, and I was transported by another bus, like a ponderous touristic bulk, to the pyramids. And then to the Egyptian Museum, that was being moved, at that very moment, to new premises. I caught the last glimpse of its dusty, nostalgic aspect. As I said, I was quite ill all that time, but I hardly had 200 or 300 meters to walk on my own feet anywhere during the trip.

It was a long postponed journey. And finally, here I am, exposed to the chilling wind of the desert that I did not quite anticipate, hiding in a group of tourists, invisible in the crowd slowly penetrating the security gates at Luxor station to catch that legendary night train to Cairo. Legendary, because I remember have read about it in any Egyptian novel.

I have read several novels before this trip, cried over Al-Haram by Yusuf Idris. Together with the great Azazeel, by Youssef Ziedan, that I had read in a French translation when I was in Tours, they make the esteem that I have of Egyptian literature. I wish I could read more, hopefully this autumn in France once again. I left my Al-Aswamy, equally a French edition, in my storage space in Leiden. Never had time enough.

On the road, nonetheless, I had something quite different to read, In an Antique Land by Amitav Ghosh, a brilliant book for the circumstance. It is a sort of mixed genre, the result of a travel made by the author as anthropologist, a young researcher collecting materials for a dissertation, penetrating deep into the human reality of Egyptian countryside; a document interwoven with autobiographic threads and historical fiction, as he tries to reconstruct, based on the documents found in Cairo's genizah, the life of a 12th c. Jewish merchant Abraham Ben Yiju, and his two slaves Ashu and Bomma, that rather surprisingly connects Egypt with his own homeland.

So, Yusuf Idris and Amitav Gosh in my pocket, this is the taste of Egypt, and the experience of that banality of being a mere tourist in an antique and dusty land, that might have some hidden connection to my own world and homeland(s).

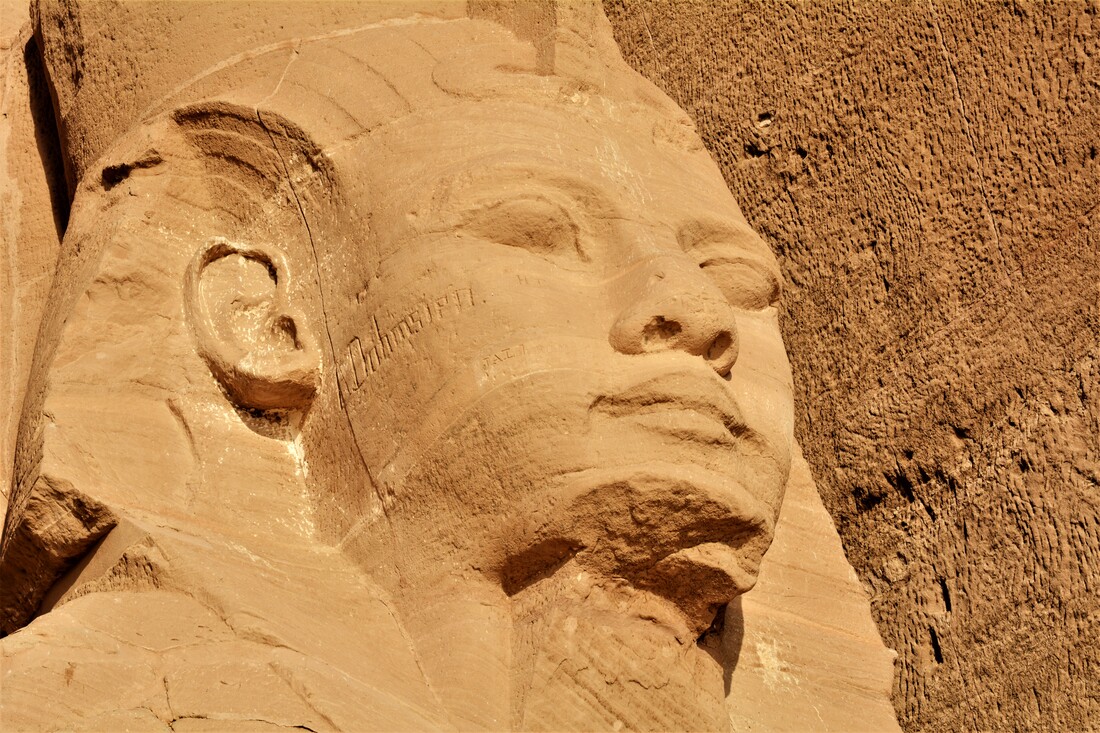

My journey started at the airport of Hurghada; from then, through a desolate desert road, I went down to Aswan, where my cruise down the Nile were to begin. Meanwhile, I also bought an additional bus trip to Abu Simbel, at 3 am, that brought me close to pneumonia and partially spoiled my journey. Or made it more difficult, with those difficulties I rarely experienced. I was never sick on any of my travels, except for two days in Armenia, where I ate one of these traditional preserves made with condensed grape juice. The nuts inside were mouldy, and I thought this is how they were supposed to be. Of course not. The mould caused some sort of acute hypotension, and at a given moment I heard the sound of duduk very far, very far from me...

The infection in Egypt was something else, shortness of breath, the sensation of missing the air, with the access of panic that comes with it. If only I could rest, I would probably overcome it easily, but I had to move from one place to another according to a chaotic, truly Egyptian planning. With a sleepless night over another sleepless night, I got as sick as I rarely was in my life. But still, the only thing I scratched from my schedule was to enter the great Cheops pyramid; I was afraid my breath might fail me while inside. I was very weak, had to stop after climbing just a few steps, panting heavily. But even though, I penetrated all the remaining holes.

Later on, it crossed my mind that my sickness could have been an early case of COVID-19, when no one heard about the disease yet. During the charter flight back home, a man from my group fainted and was given oxygen.

So, as I said, I came by bus from Hurghada to Aswan, and then, in the middle of the night, by bus to Abu Simbel, for an early morning visit of the temple. And then I spent three nights on the Nile cruiser, enjoying food, and drinks, and all sort of luxuries available to European working classes. Those cruisers were so numerous on the river that they could not reach the piers directly; several of them were attached in parallel to the quay, and the ant lines of tourists were guided across two or three or four of them till they could reach their own. When the tourists moved in the opposite direction, for their sessions of mass sightseeing, lines of hansom cabs drawn by miserable horses were waiting to take them to the main attractions, the temples I had read about as a child.

Everything was like a fairy tale nonetheless, and still quite evocative of the classical Grand Tours of the 19th century. I wandered through the Valley of the Kings after an unforgettable balloon flight and a sunrise on the Nile. Later on, as I've mentioned, I caught the night train to Cairo, and I was transported by another bus, like a ponderous touristic bulk, to the pyramids. And then to the Egyptian Museum, that was being moved, at that very moment, to new premises. I caught the last glimpse of its dusty, nostalgic aspect. As I said, I was quite ill all that time, but I hardly had 200 or 300 meters to walk on my own feet anywhere during the trip.

It was Coptic Christmas, this is why we could move from Gizeh to Tahrir Square and the Egyptian Museum so easily. But I could imagine how crowded the country actually is, that sea of miserable housing coming close to the very pyramids of Gizeh, greater than them. Nonetheless, I saw very few Egyptians, just the back of the cab driver, with whom I tried to exchange a few words in Arabic. The very fact that we took cabs, instead of walking, was a way of isolating the tourists from the natives. I could touch them on only one occasion: in the crowd swarming at Luxor train station, where every bag and package was scanned for arms and explosives. On the train, I asked the waiter to take my meal and give it to someone; certainly, I thought, there had to be a poor Muslim on that train; yet I saw none, did not come close to any, not as close as I used to come to poor Muslims in Morocco or Tunisia, where I couldn't possibly avoid giving a sadaka to a paralytic at the entrance of a mosque. I felt in my own skin that my former worries about going to Egypt were by no means exaggerated. It is a country living under a constant threat of terrorism, much more than we ever experienced in Europe. As low in the ranking of safety and democracy as a country could ever be. The tourists were separated from the natives to protect them, as carefully as possible, from participating in a fight and a destiny that was not theirs.

Not a place to spend reckless vacations, one might say. Nonetheless, it is a country where the European working classes will spend their vacations for many years to come, no matter what happens; with this uniquely numerous and uniquely miserable population, service will always be cheap, prompt, available. Myself, I spent two all-inclusive days in Hurghada, staring at the sea during the day, participating in plebeian games and distractions in the evening. Wandering aimlessly among the bungalows, I spotted a true Egyptian falcon, just like in ancient depictions, with its iconic dark pattern under the eyes.

I am here with a Polish group of tourists, on an organised trip from a Polish travel agency. Yet it comes to my mind how distant my experience actually is from any such adventure of a Polish colleague, a representative of the same academic class to which I (apparently) belong. In Blogotony (a blog published as a book in 2013) of Inga Iwasiów, the famous Polish feminist and a professor of gender studies at the University of Szczecin, I find her own travel notes from Egypt (p. 274-277). She observes Russian and Arab families, incommunicado. How they ignore each other, and ignore her, as she tries to speak English to the Russians (funny thing, Inga Iwasiów is some ten years older than me, she must have had Russian at school, just like me; either she forgot it totally, or considers beneath her to give it a try). She abhors the very idea that an Egyptian man might touch her ("Egyptian massage" kojarzył mi się raczej z balsamowaniem zwłok), let alone a perspective of having a sex intercourse with any of them (uznałabym seks z chłopakiem z plaży za wyjątkowo nieprzyjemny, bo obciążony jego przymusem, jego pogardą, jego systemem wartości, jego wiarą w konieczną czystość kobiety). The beach, as she concludes, is a tragic place, and she confesses to always return from such places z niepokojem w sercu, with anxiety in her heart. An anxiety, I presume, caused not by his, but her own unsolved wiara w konieczną czystość kobiety.

Well, personally, I have never made love with an Egyptian beach boy, but overall, I may truly say that something I have never experienced with an Arab man is his contempt, nor his "persuasion concerning the necessary purity of the woman"... First of all, as our Prophet said, pure women are for pure men; in strictly Islamic terms, those beach boys, since their sinful life is of a public nature, are unfit to marry a Muslim virgin, or even a divorcée or a widow who has never been publicly condemned for adultery; and this is for the rest of their lives; there is no confession, no penitence, no absolution, no ritual, no symbolic technique to change their polluted condition. It is good to understand that all sex workers, also males, are usually victims in a given social, economic, and symbolic status quo. Only a Polish gender scholar could see in them triumphant masculinity, ready to exert its traditional dominion.

Incidentally, I always repeat that the crucial thing is to have a good level of religious education. This is when you get a real awareness of when to sin, and why, and for what. But how a Polish gender scholar could know such things? She is immersed till the neck in Polish patriarchal imprints; her situation as a woman educated in and to patriarchal relations and as someone who makes her living and her prestige out of the fighting (never victoriously) against them forms a sort of distorting lens through which she sees the world. And her vacation in Egypt must remain a tragedy without catharsis.

As for the Russians, their presence did not derange me in the least. On the other hand, I quite appreciated seeing a couple of elderly Georgians, whom I recognized by their deeply interiorized dancing capacity that can exist nowhere else than in the Caucasus. The lady, that must have been in her seventies or more, dressed as well and with as much taste as her visibly modest budget permitted, danced with such a pleasure, and singular lightness, that it was a touching and memorable view to see.

Overall, I am not touchy and full of aversion like my colleague from the University of Szczecin. Perhaps because I did not come in search of "authenticity" (so sorely missing in beach sexual encounters) nor "intercultural communication" (so defective in the attempts of speaking English to Russians and forcing them to behave politely). The hotel in Hurghada appears to me as an anthropological reality, in its own ontological plenitude, missing nothing at all to be authentic, since it simply is, offering a direct, unmediated insight into the crisscrossing lives of men and women. As a thing in itself, not a simulacrum of anything else. It doesn't mask any void, it is its own void, quite manifestly. Perhaps I am still a traveller in the old, universalist style of Terre des hommes, of Saint-Exupéry, rather than the new, and already obsolete, simulacra style of Baudrillard. This might also be the reason why I see pathos where my colleague only sees abjection.

Amitav Ghosh, In an Antique Land, New Delhi, Ravi Dayal Publishers, 1992.

Inga Iwasiów, Blogotony, Warszawa, Wielka Litera, 2013.

Luxor, 8.01.2020 - Kraków, 2.08.2021.

It was Coptic Christmas, this is why we could move from Gizeh to Tahrir Square and the Egyptian Museum so easily. But I could imagine how crowded the country actually is, that sea of miserable housing coming close to the very pyramids of Gizeh, greater than them. Nonetheless, I saw very few Egyptians, just the back of the cab driver, with whom I tried to exchange a few words in Arabic. The very fact that we took cabs, instead of walking, was a way of isolating the tourists from the natives. I could touch them on only one occasion: in the crowd swarming at Luxor train station, where every bag and package was scanned for arms and explosives. On the train, I asked the waiter to take my meal and give it to someone; certainly, I thought, there had to be a poor Muslim on that train; yet I saw none, did not come close to any, not as close as I used to come to poor Muslims in Morocco or Tunisia, where I couldn't possibly avoid giving a sadaka to a paralytic at the entrance of a mosque. I felt in my own skin that my former worries about going to Egypt were by no means exaggerated. It is a country living under a constant threat of terrorism, much more than we ever experienced in Europe. As low in the ranking of safety and democracy as a country could ever be. The tourists were separated from the natives to protect them, as carefully as possible, from participating in a fight and a destiny that was not theirs.

Not a place to spend reckless vacations, one might say. Nonetheless, it is a country where the European working classes will spend their vacations for many years to come, no matter what happens; with this uniquely numerous and uniquely miserable population, service will always be cheap, prompt, available. Myself, I spent two all-inclusive days in Hurghada, staring at the sea during the day, participating in plebeian games and distractions in the evening. Wandering aimlessly among the bungalows, I spotted a true Egyptian falcon, just like in ancient depictions, with its iconic dark pattern under the eyes.

I am here with a Polish group of tourists, on an organised trip from a Polish travel agency. Yet it comes to my mind how distant my experience actually is from any such adventure of a Polish colleague, a representative of the same academic class to which I (apparently) belong. In Blogotony (a blog published as a book in 2013) of Inga Iwasiów, the famous Polish feminist and a professor of gender studies at the University of Szczecin, I find her own travel notes from Egypt (p. 274-277). She observes Russian and Arab families, incommunicado. How they ignore each other, and ignore her, as she tries to speak English to the Russians (funny thing, Inga Iwasiów is some ten years older than me, she must have had Russian at school, just like me; either she forgot it totally, or considers beneath her to give it a try). She abhors the very idea that an Egyptian man might touch her ("Egyptian massage" kojarzył mi się raczej z balsamowaniem zwłok), let alone a perspective of having a sex intercourse with any of them (uznałabym seks z chłopakiem z plaży za wyjątkowo nieprzyjemny, bo obciążony jego przymusem, jego pogardą, jego systemem wartości, jego wiarą w konieczną czystość kobiety). The beach, as she concludes, is a tragic place, and she confesses to always return from such places z niepokojem w sercu, with anxiety in her heart. An anxiety, I presume, caused not by his, but her own unsolved wiara w konieczną czystość kobiety.

Well, personally, I have never made love with an Egyptian beach boy, but overall, I may truly say that something I have never experienced with an Arab man is his contempt, nor his "persuasion concerning the necessary purity of the woman"... First of all, as our Prophet said, pure women are for pure men; in strictly Islamic terms, those beach boys, since their sinful life is of a public nature, are unfit to marry a Muslim virgin, or even a divorcée or a widow who has never been publicly condemned for adultery; and this is for the rest of their lives; there is no confession, no penitence, no absolution, no ritual, no symbolic technique to change their polluted condition. It is good to understand that all sex workers, also males, are usually victims in a given social, economic, and symbolic status quo. Only a Polish gender scholar could see in them triumphant masculinity, ready to exert its traditional dominion.

Incidentally, I always repeat that the crucial thing is to have a good level of religious education. This is when you get a real awareness of when to sin, and why, and for what. But how a Polish gender scholar could know such things? She is immersed till the neck in Polish patriarchal imprints; her situation as a woman educated in and to patriarchal relations and as someone who makes her living and her prestige out of the fighting (never victoriously) against them forms a sort of distorting lens through which she sees the world. And her vacation in Egypt must remain a tragedy without catharsis.

As for the Russians, their presence did not derange me in the least. On the other hand, I quite appreciated seeing a couple of elderly Georgians, whom I recognized by their deeply interiorized dancing capacity that can exist nowhere else than in the Caucasus. The lady, that must have been in her seventies or more, dressed as well and with as much taste as her visibly modest budget permitted, danced with such a pleasure, and singular lightness, that it was a touching and memorable view to see.

Overall, I am not touchy and full of aversion like my colleague from the University of Szczecin. Perhaps because I did not come in search of "authenticity" (so sorely missing in beach sexual encounters) nor "intercultural communication" (so defective in the attempts of speaking English to Russians and forcing them to behave politely). The hotel in Hurghada appears to me as an anthropological reality, in its own ontological plenitude, missing nothing at all to be authentic, since it simply is, offering a direct, unmediated insight into the crisscrossing lives of men and women. As a thing in itself, not a simulacrum of anything else. It doesn't mask any void, it is its own void, quite manifestly. Perhaps I am still a traveller in the old, universalist style of Terre des hommes, of Saint-Exupéry, rather than the new, and already obsolete, simulacra style of Baudrillard. This might also be the reason why I see pathos where my colleague only sees abjection.

Amitav Ghosh, In an Antique Land, New Delhi, Ravi Dayal Publishers, 1992.

Inga Iwasiów, Blogotony, Warszawa, Wielka Litera, 2013.

Luxor, 8.01.2020 - Kraków, 2.08.2021.

How to become a mere tourist? A mere tourist would neither notice nor appreciated the fact that the little enterprise organising balloon flights has al-hud (the hoopoe) for its trademark. The mystical bird who led other birds through seven valleys, on their great journey in search of God.

I am afraid that, for much that I try, I will never become a mere tourist. Definitely, there are too many bibliographical references around my head, transforming the world into the territory of an erudite Grand Tour, eventually, but closing in front of me the golden gates of the touristic experience as a mere thoughtlessness in the sun...

Well, after all, I can at least cultivate the art of "being myself" during my vacation. Even if becoming a tourist is a closed gate, I can still enjoy what I am, i.e. an erudite. Which is also an almost orgasmic source of satisfaction.

I am afraid that, for much that I try, I will never become a mere tourist. Definitely, there are too many bibliographical references around my head, transforming the world into the territory of an erudite Grand Tour, eventually, but closing in front of me the golden gates of the touristic experience as a mere thoughtlessness in the sun...

Well, after all, I can at least cultivate the art of "being myself" during my vacation. Even if becoming a tourist is a closed gate, I can still enjoy what I am, i.e. an erudite. Which is also an almost orgasmic source of satisfaction.

on the Nile

|

It was a beautiful cruise, in spite of the surprize: a chilling desert wind of January. I hide in my cosy cabin, observing the river from my bed. The food was overabundant, although it was lacking style: a mix of international delicacies with some doubtful local ones, such as the unavoidable foul mudammas (fava beans).

Yet another obligation of a mere tourist is to participate in the peculiar "throwing" trade: several small boats approach the cruisers immobilised at the Esna lock on the Nile, proposing to the tourists the acquisition of various "typical" textiles that they throw, with a great agility, right into the balconies and open windows on the ship; the money is equally to be thrown down in a plastic bag. I acquired, for five dollars, one of those rough scarfs that the cab drivers wear (they must be made in China to become so common among such a numerous population). A curious "guarantee of origin" with a little woven gazelle persuaded me that it is the only authentic and original Egyptian product (beware of imitations). |

a ride through temples

Nubia

Travelling among the Nubian temples, I follow the memoire of Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, an eminent French archaeologist who played an important role in the UNESCO 1960 campaign that ended up moving some fourteen temples from the flooded area, the most famous those of Abu Simbel and Philae (without forgetting the little Isis temple from Taffa where I used to spend my meditating hours, reconstructed in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden).

The first dam in Aswan was built by the English in 1898-1902. It was developed further in 1907-1912, and then 1929-1934, Already at that moment, many temples were under water:

The first dam in Aswan was built by the English in 1898-1902. It was developed further in 1907-1912, and then 1929-1934, Already at that moment, many temples were under water:

Mais ceux des ainsi submergés, bien que noyés neuf mois de l'annéé, n'étaient pas complètement perdus. Ils resurgissaient de l'onde dès l'ouverture des vannes de la grande muraille en granite rose pour permettre à l'eau, enrichie des alluvions -- depuis les grands lacs et sur tout son percours -- de se répandre entièrement sur la terre d'Égypte.

Alors la Nubie reprenait un peu son aspect antique. On voyait réapparaître les palmiers, aux trois quarts noyés durant neuf mois, mais qui résistaient aussi, annuellement, en dressant leurs seules têtes touffues au-dessus de l'eau pendant l'inondation. Sur les rives, une végétation vert émeraude, poussée par miracle, donnait des récoltes riches et rapides, en même temps la population paraissait brusquement découplée, avec le retour des hommes valides, en congé d'été, venus faire connaissance avec leurs rejetons procréés à leur dernier passage.

Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, La Grande Nubiade. Le parcours d'une égyptologue, Paris, Stock/Pernoud, 1992, p. 197.

Abu Simbel | أبو سمبل

|

Philae | فيله | Φιλαί | ⲡⲓⲗⲁⲕ

The Temple of Isis (7th - 6th c. BC)

Les édifices érigés dans l'île sainte, à l'Occident, étaient consacrés à l'entité osirienne plongée dans une mort provisoire. La region orientale, située dans le creux évoquant le dos de l'oiseau, devait rappeler le réveil de la nature, la joie du renouveau, le retour de la déesse qui, des entrailles de l'Afrique, revenait avec l'inondation salvatrice. (...) Il était interdit, dans la partie occidentale de l'île, de parler haut, de chanter, de faire du bruit et même de jouer de la musique. C'était la zone du silence succédant au deuil extériorisé. Il ne fallait pas davantage y chasser ni même pêcher. En revanche, à l'est de l'île, s'était l'éclatement de la joie, du bonheur, de l'exaltation. Les servants de la déesse y exécutaient des danses et des jeux: la musique des hautbois, des harpes et des luths exprimait l'espoir et la satisfaction du monde à l'arrivée de l'an nouveau.

De fait, le grand kiosque d'Hadrien ou de Trajan, édifié pour y recevoir une des barques de la déesse, revenant mystiquement de son voyage, jouxtait presque la charmante chapelle d'Hathor, ornée d'un pronaos periptère (...) dans laquelle devaient passer chanteuses et chorégraphes de la déesse lorsqu'elles se rendaient sur l'esplanade donnant sur le Nil.

Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, La Grande Nubiade..., p. 412-413.

Luxor | الأقصر | ⲡⲁⲡⲉ | Thebes | Diospolis | ⲡϣⲟⲙⲧ ⲛ̀ⲕⲁⲥⲧⲣⲟⲛ | "the three palaces"

One of those fuzzy dreams of childhood, that should stand bold in my mind, yet for the adult tourist, tired of the world, inevitably merges with all the other columns, all the remaining Egypt. I suppose it was about this, the city of Thebes and Ramses II that the Bolesław Prus' Pharaoh was all about, and that movie of Jerzy Kawalerowicz where my interest in Egypt began, when I was eight. Yet now, on a rainy day when I return to my Egyptian trip and wish to finish my website, I can hardly disentangle my photos to see which actually one was that Temple of Luxor, its giant Ramses II statue and its hypostyle hall. That's the misery of being a tourist, that's the shame of not taking careful notes, the pity of not sketching, like the 19th-century travellers would do. Would it actually help?

Right now, I try to consolidate my memories, Internet coming to my aid, and to understand where I have actually been, and for what. What kind of wisdom did that travel bring to me. Trying to persuade myself that I actually deserved it, rather than to stay on one of those luxury boats on the Nile, consuming my crevettes.

Ah, here it is, it was the one we visited at night, perhaps the travel agency believed it will look more mysterious like this, or perhaps wished to avoid the heat, oblivious of the fact it was January. Or for no reason whatsoever, except the typical Egyptian chaos.

Right now, I try to consolidate my memories, Internet coming to my aid, and to understand where I have actually been, and for what. What kind of wisdom did that travel bring to me. Trying to persuade myself that I actually deserved it, rather than to stay on one of those luxury boats on the Nile, consuming my crevettes.

Ah, here it is, it was the one we visited at night, perhaps the travel agency believed it will look more mysterious like this, or perhaps wished to avoid the heat, oblivious of the fact it was January. Or for no reason whatsoever, except the typical Egyptian chaos.

Valley of the Kings

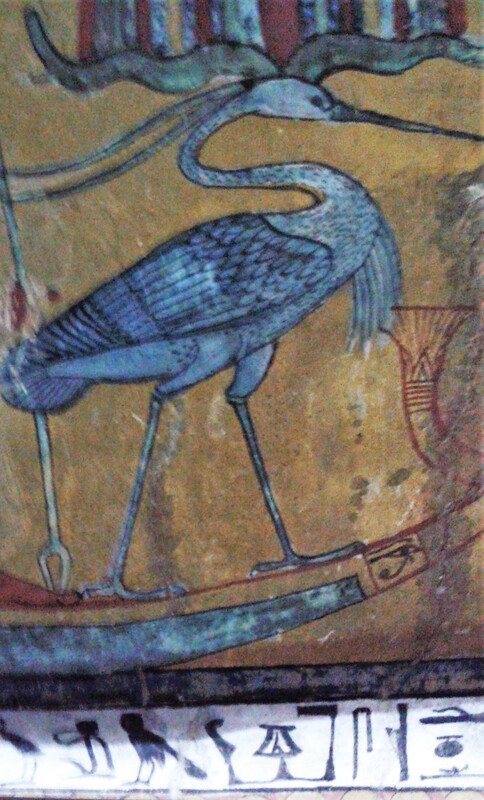

The traveller exhausted by the emotions of a balloon flight at dawn arrives to the dusty Valley of the Kings, with I don't know how many tombs to visit. Not all of them open to the public, and the ticket, if I remember it correctly, only permits a choice of a certain number of them. Yet it is enough, again, to boggle my mind.

This is why I dutifully paid for the additional ticket permitting to take my own pictures, even if I certainly have many of those images reproduced in high resolution and under much better light in those many cumbersome albums about Egypt that I infest my flat in Kraków. I just wanted a bit of that climate, even if the place was, in the first place, so dusty, so crowded, so tiring, so overexploited, so emptied of any trace of mystery and romance.

This is why I dutifully paid for the additional ticket permitting to take my own pictures, even if I certainly have many of those images reproduced in high resolution and under much better light in those many cumbersome albums about Egypt that I infest my flat in Kraków. I just wanted a bit of that climate, even if the place was, in the first place, so dusty, so crowded, so tiring, so overexploited, so emptied of any trace of mystery and romance.

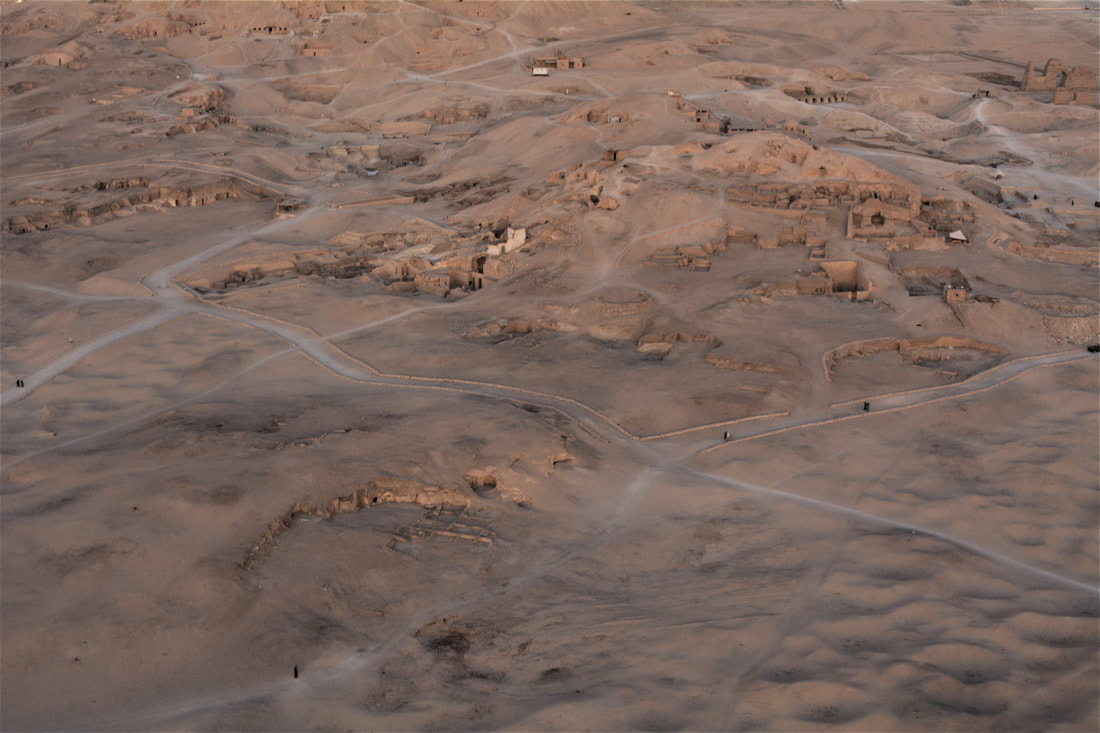

Deir al-Medina, the worker's village

|

Those graves are small, many chambers are just a couple of square meters. They belong to simple people, many of them the workers employed on the great pharaonic endeavours, but they make a particular impression. Of a country that was for all, not only for the narrow privileged caste. In its shadow, average lives went on, and average dead found their way to the afterlife.

|

Al-Qahira, arriving at the train station

|

There is always something to return to. In my case, it would be Cairo, the old Cairo of mosques and bazars. The train from Luxor brought me, and my group of tourists, to a train station that gives a taste of the city, of its crowds, of its dangers. I don't believe in the least the efficiency of the gates that were supposed to discover explosives in all those volumes and packages that people were carrying in and out like giant ants. The bus was expecting us at the entrance, and the day corresponded to the Coptic Christmas. This is how we arrived to the Tahrir Square. And all what I saw of Cairo was a dusty jungle of housing, and the Egyptian Museum ready for some sort of reformation. I still saw it, partially packed, in its old form, lacking paint in various places, scratched and chaotic. In the Museum shop I spent the rest of my money on reproductions of early 20th c. lithographs of the old Cairo. Pity I didn't brought any book for my library.

I need to see this city with my own eyes, as well as Alexandria. Alone, risking my life, swollen by a country of too many. Perhaps after some new revolution, inshallah. Cairo, January 10th, 2020. |

my readings in Egyptian literature

the saddest book

The Tent, by Miral al-Tahawy

There are many sad books in Egypt; arguably, all Egyptian books are sad. But that one is the saddest of all, counting the story of a solitary girl with an amputated leg, daughter of a weeping woman (that would be a case of depression, perhaps, in modern terms), a victim of her paternal grandmother, a victim of the ancestral violence of woman against woman. And this contrasted, perhaps deliberately for the Western eye, with the glories of the Bedouin life, an Arabian horse and a falcon. There is an English woman in the background, Ann (as if Ann Blunt?), who wants to steal those glories: she projects to establish rare lines of horses with the progeny of Fatima's favourite white mare, mating with various champions of European races. As the occasion presents itself, she would be also keen to steal Fatima's story, her art of storytelling, those fantastic narrations that appear as a modern 1001 night. It is also the foreigner who is instrumental in the girl's amputation; otherwise, she would simply die of gangrene that developed in the neglected leg wounded as she falls down from a tree. For this is how all Arab women's dreams of freedom always end. There is a fall and a gangrene, despite all the benevolent Englishwomen so keen to give them trilingual education.

So this is how the novel develops, counting Fatima's childhood and early youth, and her later life, so deeply sad that it doesn't even makes me cry. The girl is accompanied by a ghost of a gazelle, hunted by her father, deliberately caught alive to become his daughter's pet. But the gazelle did not survive. Just as the Bedouin's wife did not survive his love. Slowly, she bleeds to death, bleeding tears and blood. Because of her multiple miscarriages, apparently. Because of her inability of giving her husband a male hair. Because of the cruelty of her mother-in-law, probably. Because of the ancestral contempt of women toward themselves, by which they do not consider themselves truly worth living. So the mother cries, and bleeds, and cries, and bleeds, and finally, she cries and bleeds to death. The father marries another woman, only to depart hunting merely a week later. For such is the solitude of the Arab man, also contributing to the novel's pervasive sadness. The solitude and the cowardness of a Bedouin who is not brave enough to accept the challenge of love, not brave enough to confront his mother, not brave enough, even, to see his daughter after her amputation. A man who bears his desert as a monstrous pregnancy, like in Nietzsche's Dionysian dithyrambs (Die Wüste wächst: weh Dem, der Wüsten birgt!).

Miral al-Tahawy, born to al-Hanadi tribe in the eastward part of the Nile delta, has been considered a precursor, someone giving voice, for the first time, to the Egyptian Bedouin women. That is a well-intentioned, Western interpretation. But what I hear is a millenarian lament, the very matter of which female expression is traditionally made pretty well everywhere in the Middle East. A lingering lament of Umm Kulthum, suspended at the uttermost point of its affective intensity, made literature, but also more than this. There is lament as a major modus of expression of the first Arabian she-poets, close to the Prophet's time, even older than Islam; the long shadow of Jahiliya is somehow present, subtly evoked in her novel. This is why I would rather see the writer as a closure of a millennium, an explorer of all things primordial, not a precursor of anything to come. But obviously, I loved the book, with its Arabian horse, and its she-falcon, and its dead gazelle, and its ghouls, and the constellation named after Nash and his daughters (Benetnash, i.e. Ursa Major), and the seven palm trees at the well, where seven unwanted daughters had been buried alive.

Miral al-Tahawy, الخباء | The Tent (1996). Read in a Polish translation: Namiot Fatimy, trans. Izabela Szybilska-Fiedorowicz, Sopot - Londyn: Smak Słowa, 2009.

Kraków, 12.08.2022.

So this is how the novel develops, counting Fatima's childhood and early youth, and her later life, so deeply sad that it doesn't even makes me cry. The girl is accompanied by a ghost of a gazelle, hunted by her father, deliberately caught alive to become his daughter's pet. But the gazelle did not survive. Just as the Bedouin's wife did not survive his love. Slowly, she bleeds to death, bleeding tears and blood. Because of her multiple miscarriages, apparently. Because of her inability of giving her husband a male hair. Because of the cruelty of her mother-in-law, probably. Because of the ancestral contempt of women toward themselves, by which they do not consider themselves truly worth living. So the mother cries, and bleeds, and cries, and bleeds, and finally, she cries and bleeds to death. The father marries another woman, only to depart hunting merely a week later. For such is the solitude of the Arab man, also contributing to the novel's pervasive sadness. The solitude and the cowardness of a Bedouin who is not brave enough to accept the challenge of love, not brave enough to confront his mother, not brave enough, even, to see his daughter after her amputation. A man who bears his desert as a monstrous pregnancy, like in Nietzsche's Dionysian dithyrambs (Die Wüste wächst: weh Dem, der Wüsten birgt!).

Miral al-Tahawy, born to al-Hanadi tribe in the eastward part of the Nile delta, has been considered a precursor, someone giving voice, for the first time, to the Egyptian Bedouin women. That is a well-intentioned, Western interpretation. But what I hear is a millenarian lament, the very matter of which female expression is traditionally made pretty well everywhere in the Middle East. A lingering lament of Umm Kulthum, suspended at the uttermost point of its affective intensity, made literature, but also more than this. There is lament as a major modus of expression of the first Arabian she-poets, close to the Prophet's time, even older than Islam; the long shadow of Jahiliya is somehow present, subtly evoked in her novel. This is why I would rather see the writer as a closure of a millennium, an explorer of all things primordial, not a precursor of anything to come. But obviously, I loved the book, with its Arabian horse, and its she-falcon, and its dead gazelle, and its ghouls, and the constellation named after Nash and his daughters (Benetnash, i.e. Ursa Major), and the seven palm trees at the well, where seven unwanted daughters had been buried alive.

Miral al-Tahawy, الخباء | The Tent (1996). Read in a Polish translation: Namiot Fatimy, trans. Izabela Szybilska-Fiedorowicz, Sopot - Londyn: Smak Słowa, 2009.

Kraków, 12.08.2022.

|

Vertical Divider

|

|

killing an Arab

Standing on a beach

With a gun in my hand

Staring at the sea

Staring at the sand

Staring down the barrel

At the Arab on the ground

See his open mouth

But hear no sound

I’m alive

I’m dead

I’m the stranger

Killing an Arab

(Robert Smith's lyrics of a song from The Cure's LP disc "Boys Don't Cry", 1980)

It's many years, decades even since I've read anything of Naguib Mahfouz. But the summer always brings the thought of Egypt, and I finally read a Polish translation of the 1961 short novel Al-liss wa al-kilab (The Thief and the Dogs) that I bought many years ago.

I've read Mahfouz as a teenager, in what might be rightly called his time. But at that moment I wasn't fully aware (although it would be the time to notice such things) of how strong is the existentialist taste of the Egyptian writer. I used to see in him the exotic part; but as I return to him now, I can see how European he actually was. How deeply syntonized. This is what they all used to be at the time, all those decolonial writers. Syntonized. Aware of their time. The exploration of their own tradition would come later.

So as I read my Polish translation of Al-liss wa al-kilab, I feel the aftertaste of Sartre and Camus, just as there was Sartre in Cheikh Hamidou Kane, exactly at the same time, at the beginning of the 1960s. I suppose one day the name "Sartre" will bring to the reader's mind the atmosphere of a zawiya or a quranic school more than any place in Paris, (because no one will read the man for his own sake, just keep him as a reference while reading those African writers). It is, in any case, to an old sheikh's home that the existential hero of Mahfouz goes right after being released from his prison and rejected at his former home. It is to a holy man that he tries to speak, and the dialogue between the mystic and the ex-prisoner tortured by anger and thirst for revenge illustrates the existentialist supposition of human incommunicability, the essential isolation. There is also something vaguely political in the background that is not exactly about Egyptian politics and the Egyptian revolution, but more generally about the bitterness of modernity, the essential disillusion with ideologies. And this is why Said Mahran wants to kill not only the man who stole his wife and daughter but also the journalist Rauf Ulwan, who taught him false truths in the old times of their youthful activism. But of course, as soon as existentialism comes to the fore, the hazard and the absurdity lurk in the background. No wonder Said repeatedly kills the wrong persons. The attempt at taking his revenge on the man who denounced him to the police to conquer his wife (and whatever he left to her at the moment of his imprisonment) encounters some degree of popular support. But another missed attempt, resulting in the death of an innocent guard instead of the targeted journalist, definitely gives rise to a manhunt. It becomes clear that Said is not just playing the sort of game accepted by this society.

There is more to say about Said. Obsessed by his revenge, he is too slow to appreciate the love of Nour, a prostitute who offers him a safe haven in her little place with a view over a cemetery. Only at the moment of his utter confrontation with the "dogs" that he realizes all the depth of his attachment to her. Too late.

Said Mahran is just another Meursault killing an Arab (they are all Arabs), absurdly, because of the bright sunlight. Metaphorically speaking, of course, because in Mahfouz's novel it all happens at night. But the importance of writing it, in Egypt, is not just to become another Camus, but to join something, to get access, to become modern. Unabashed. The novel legitimizes the claim.

Naguib Mahfouz, Al-liss wa al-kilab (1961). Read in a Polish translation: Złodziej i psy, trans. Jacek Stępiński, Warszawa, PIW, 2007.

Kraków, 11.08.2022.

I've read Mahfouz as a teenager, in what might be rightly called his time. But at that moment I wasn't fully aware (although it would be the time to notice such things) of how strong is the existentialist taste of the Egyptian writer. I used to see in him the exotic part; but as I return to him now, I can see how European he actually was. How deeply syntonized. This is what they all used to be at the time, all those decolonial writers. Syntonized. Aware of their time. The exploration of their own tradition would come later.

So as I read my Polish translation of Al-liss wa al-kilab, I feel the aftertaste of Sartre and Camus, just as there was Sartre in Cheikh Hamidou Kane, exactly at the same time, at the beginning of the 1960s. I suppose one day the name "Sartre" will bring to the reader's mind the atmosphere of a zawiya or a quranic school more than any place in Paris, (because no one will read the man for his own sake, just keep him as a reference while reading those African writers). It is, in any case, to an old sheikh's home that the existential hero of Mahfouz goes right after being released from his prison and rejected at his former home. It is to a holy man that he tries to speak, and the dialogue between the mystic and the ex-prisoner tortured by anger and thirst for revenge illustrates the existentialist supposition of human incommunicability, the essential isolation. There is also something vaguely political in the background that is not exactly about Egyptian politics and the Egyptian revolution, but more generally about the bitterness of modernity, the essential disillusion with ideologies. And this is why Said Mahran wants to kill not only the man who stole his wife and daughter but also the journalist Rauf Ulwan, who taught him false truths in the old times of their youthful activism. But of course, as soon as existentialism comes to the fore, the hazard and the absurdity lurk in the background. No wonder Said repeatedly kills the wrong persons. The attempt at taking his revenge on the man who denounced him to the police to conquer his wife (and whatever he left to her at the moment of his imprisonment) encounters some degree of popular support. But another missed attempt, resulting in the death of an innocent guard instead of the targeted journalist, definitely gives rise to a manhunt. It becomes clear that Said is not just playing the sort of game accepted by this society.

There is more to say about Said. Obsessed by his revenge, he is too slow to appreciate the love of Nour, a prostitute who offers him a safe haven in her little place with a view over a cemetery. Only at the moment of his utter confrontation with the "dogs" that he realizes all the depth of his attachment to her. Too late.

Said Mahran is just another Meursault killing an Arab (they are all Arabs), absurdly, because of the bright sunlight. Metaphorically speaking, of course, because in Mahfouz's novel it all happens at night. But the importance of writing it, in Egypt, is not just to become another Camus, but to join something, to get access, to become modern. Unabashed. The novel legitimizes the claim.

Naguib Mahfouz, Al-liss wa al-kilab (1961). Read in a Polish translation: Złodziej i psy, trans. Jacek Stępiński, Warszawa, PIW, 2007.

Kraków, 11.08.2022.

|

Vertical Divider

|

pre-modern vs modern fear

|