what is Georgian literature?

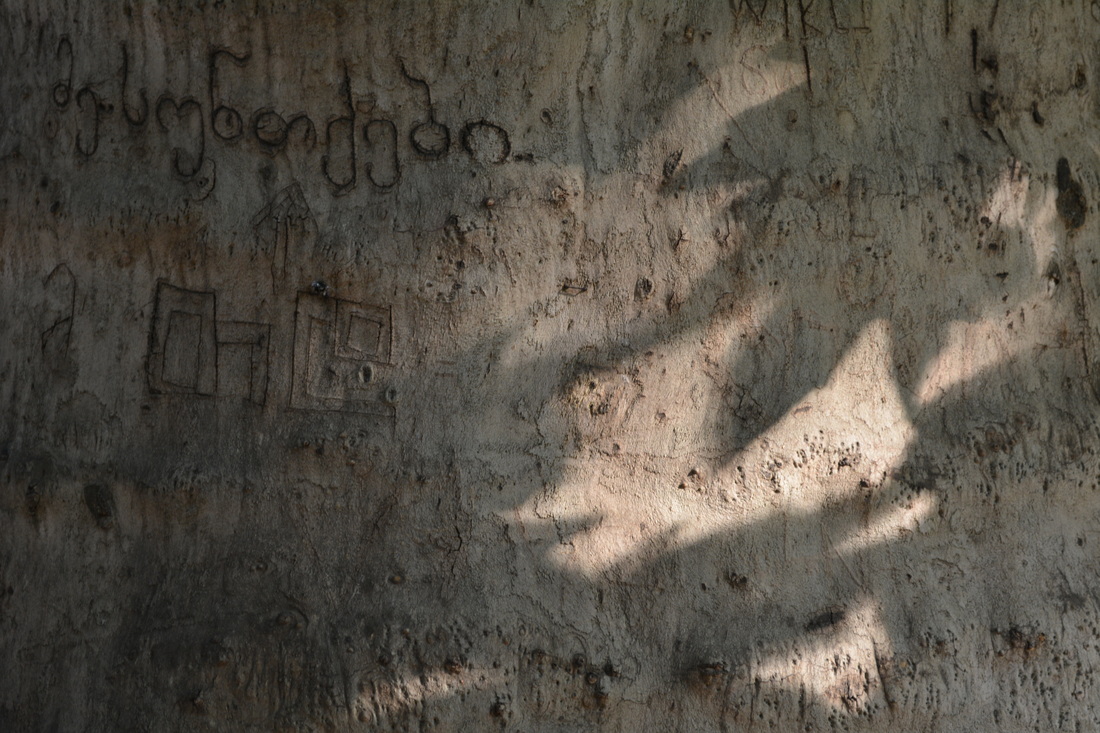

Georgian literature has deep roots. It dates back to the first millennium of Christianity. Georgian script, a unique alphabet used exclusively for the Georgian language, contributed to preserving its idiosyncratic features, yet even before the country had a vibrant oral tradition of storytelling, epic poetry, and folklore. The introduction of Christianity to Georgia is attributed to Saint Nino, who is said to have converted King Mirian III and Queen Nana in the early 4th century. Still, in the 4th century, the Georgian alphabet, known as the "Mkhedruli" script, was created by King Parnavaz I and his scribe Asomtavruli. The development of written literature in those early centuries was closely connected with Christian identity. Yet Georgian culture remained open to exterior influence. The country's geographical location exposed it to various cultural influences. During the medieval period, Persian and Arabic literary traditions had an impact on Georgian literature, leading to the incorporation of Persian poetic forms and themes. Between the 11th and 13th centuries, the Turkish and Mongol invasions led to political instability and the disruption of cultural and literary activities. However, Georgian literature persisted, adapting to the changing circumstances and continuing to thrive, and the same period is also qualified as the Georgian Golden Age. The major medieval text was composed in the 12th c. by Shota Rustaveli, and it is the famous Vepkhistqaosani (The Knight in the Panther's Skin). Yet the "Shota Rustaveli era" also saw the flourishing of religious writings, including hagiographies, hymns, and theological treatises.

Later on, the cultural history of the country, and of all the Caucasus, had its ups and downs. The country seems to have declined with the end of the Middle Ages. Only much later, the 17th and 18th centuries marked a period of literary renaissance in Georgia. The works of figures like Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani and King Vakhtang VI are notable from this era. However, the following decades saw a decline in cultural and literary achievements due to various geopolitical challenges and most importantly, Russian incursions. Despite them, the 19th century witnessed a revival of Georgian national identity and cultural consciousness. The development of modern Georgian literature gained momentum with writers like Ilia Chavchavadze, Akaki Tsereteli, and Vazha-Pshavela, who played key roles in shaping the cultural landscape.

Yet Georgian cultural identity was constantly on the brink all along the modern era, to such a degree that for a long time, the most widely known "Georgian" novel was written in German and published in Vienna in 1934; obviously, I speak about Ali und Nino, the famous love story published under the pseudonym Kurban Said. Rather surprisingly, this tradition of Georgian writing in German has a posterity, if we think about Nino Haratischwili and her novels such as Die Katze und der General, thematising the war in Chechnya, published in 2018.

Yet I'm anticipating the events. The first thing that must be said is that poetry plays a major role in Georgian literature and that its feable projection abroad is in a large measure a problem of translatability. Caucasian languages are known for their uniqueness and almost unsurmountable difficulty. Be that as it may, there are several names of highly reputed poets: Galaktion Tabidze, Akaki Tsereteli, and Nikoloz Baratashvili.

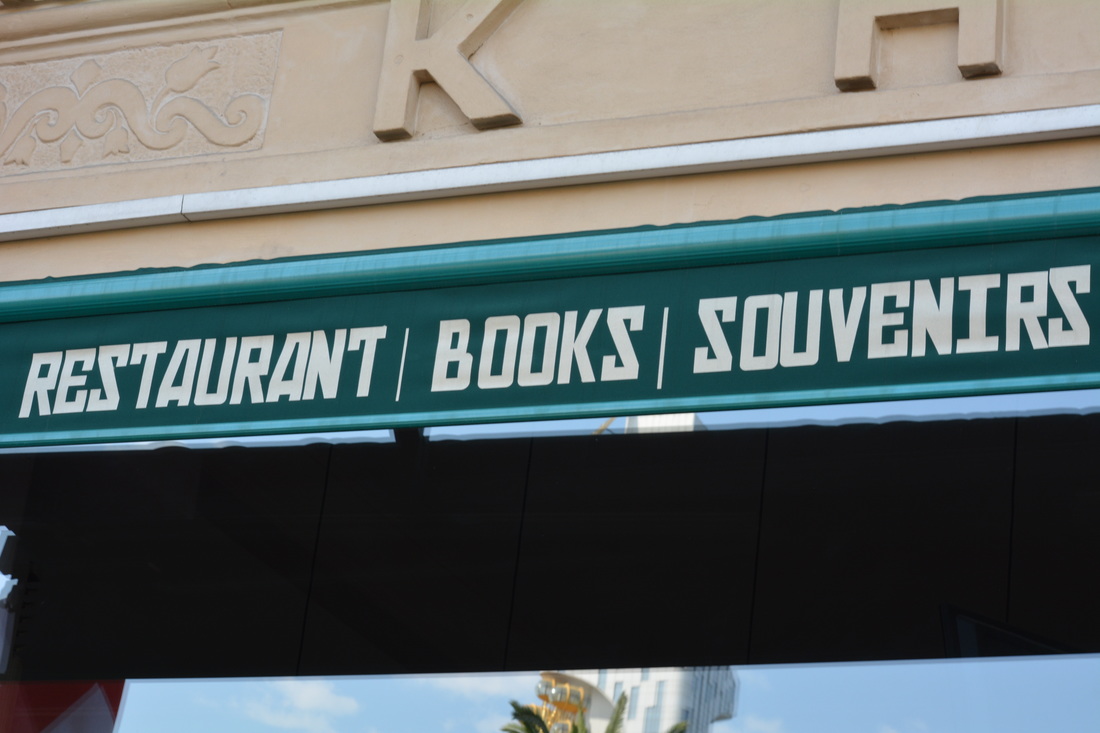

Narrative literature is of course easier to translate. Among the writers who gained renown in the 19th and the 20th c. there are such names as Ilia Chavchavadze, Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, and Mikheil Javakhishvili. Finally, as a global reader may search for a Georgian novel, there are such authors as Aka Morchiladze and Dato Turashvili, the author of an absolute best-seller of the era that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, Flight from the USSR.

Later on, the cultural history of the country, and of all the Caucasus, had its ups and downs. The country seems to have declined with the end of the Middle Ages. Only much later, the 17th and 18th centuries marked a period of literary renaissance in Georgia. The works of figures like Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani and King Vakhtang VI are notable from this era. However, the following decades saw a decline in cultural and literary achievements due to various geopolitical challenges and most importantly, Russian incursions. Despite them, the 19th century witnessed a revival of Georgian national identity and cultural consciousness. The development of modern Georgian literature gained momentum with writers like Ilia Chavchavadze, Akaki Tsereteli, and Vazha-Pshavela, who played key roles in shaping the cultural landscape.

Yet Georgian cultural identity was constantly on the brink all along the modern era, to such a degree that for a long time, the most widely known "Georgian" novel was written in German and published in Vienna in 1934; obviously, I speak about Ali und Nino, the famous love story published under the pseudonym Kurban Said. Rather surprisingly, this tradition of Georgian writing in German has a posterity, if we think about Nino Haratischwili and her novels such as Die Katze und der General, thematising the war in Chechnya, published in 2018.

Yet I'm anticipating the events. The first thing that must be said is that poetry plays a major role in Georgian literature and that its feable projection abroad is in a large measure a problem of translatability. Caucasian languages are known for their uniqueness and almost unsurmountable difficulty. Be that as it may, there are several names of highly reputed poets: Galaktion Tabidze, Akaki Tsereteli, and Nikoloz Baratashvili.

Narrative literature is of course easier to translate. Among the writers who gained renown in the 19th and the 20th c. there are such names as Ilia Chavchavadze, Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, and Mikheil Javakhishvili. Finally, as a global reader may search for a Georgian novel, there are such authors as Aka Morchiladze and Dato Turashvili, the author of an absolute best-seller of the era that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, Flight from the USSR.

I have readNino Haratischwili, Die Katze und der General (2018)

Marcin Sawicki, Pestki winorośli i trzy jabłka. Reportaże z podróży do Gruzji i Armenii (2014) Dato Turashvili, Flight from the USSR (2008) Kurban Said, Ali und Nino (1934) Shota Rustaveli, The Knight in the Panther's Skin (12th c.) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have writtenTranscultural writing and non-hegemonic universalism. Reading Ali und Nino in the context of global literary studies

Expendable lives. Catastrophe and resilience in Dato Turashvili's Flight from the USSR and Ruta Sepetys' Salt to the Sea |

in search of the essence of Georgian art

the real presence

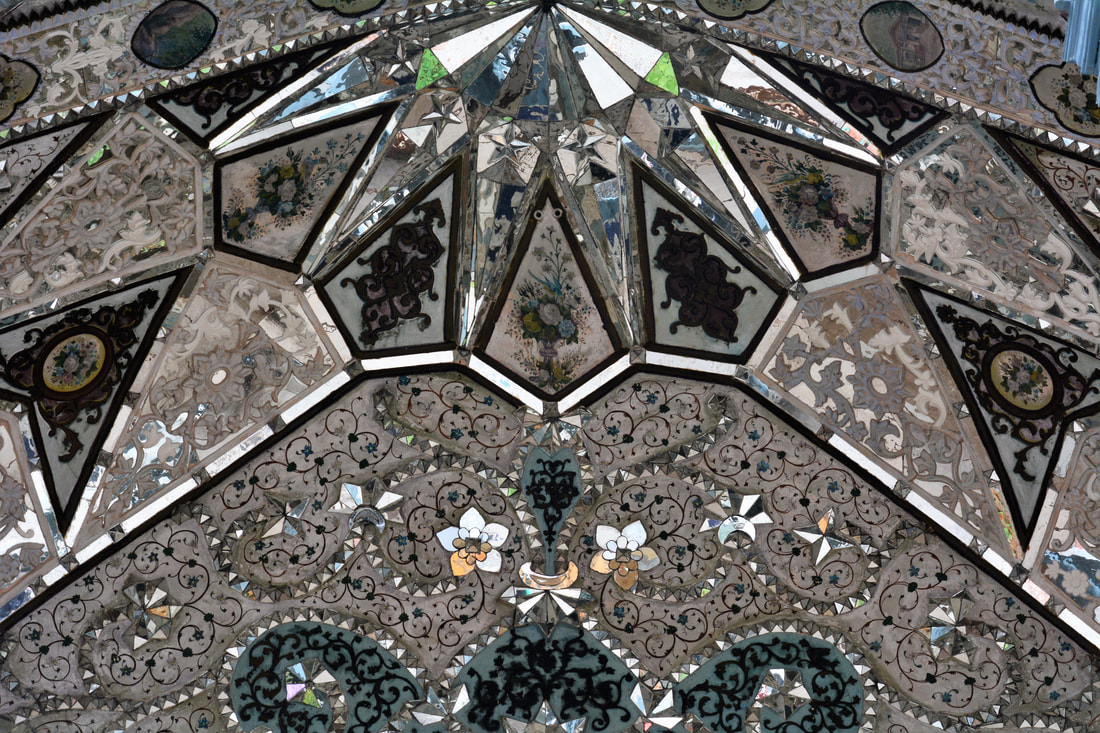

What is usually said about the peculiarity of Georgian art is that it developed at the crossroad of civilisations and that it is uniquely in accordance with its environment (as for architecture, where the oneness with scenic landscapes is in many cases truly difficult to overlook). What I notice for my own private appreciation is this unique richness of imagination, that is neither eastern nor western, but born in between, in the peripheral, borderland regions such as Kakheti, the homeland of the celebrated primitive painter Niko Pirosmani. Also, --perhaps, as far as my very superficial insight into Georgian culture could enable me to judge about such things--, the unique sense of taking things seriously, the literal treatment of the sacred (that once used to be called "the real presence"), that is today very hard to find anywhere in the Christian world.

What does it mean that Georgia is at a crossroad of civilizations? It was already valid in the Antiquity, because of the contacts between gold-rich Colkhida in Western Georgia and the Aegean cities. On the other hand, the crossroad stretched toward the Central Asia, to what I privately call "the Persian world" (Persianate is sometimes used as a more professional term, with equally vague "Balkan to Bengal" range). There is thus a Hellenistic culture in its full right, with bath-houses and ceramic masks of Dionysus and Ariadne found in Sarkineti, an ancient site in the vicinity of Iberia's (the Caucasian Iberia's) first capital, Mtskhetha. But the most famous cultural treasure of the time is the metalwork in bronze, silver and gold, perhaps the most famous aspect of Georgian artistic heritage in an international perspective.

What does it mean that Georgia is at a crossroad of civilizations? It was already valid in the Antiquity, because of the contacts between gold-rich Colkhida in Western Georgia and the Aegean cities. On the other hand, the crossroad stretched toward the Central Asia, to what I privately call "the Persian world" (Persianate is sometimes used as a more professional term, with equally vague "Balkan to Bengal" range). There is thus a Hellenistic culture in its full right, with bath-houses and ceramic masks of Dionysus and Ariadne found in Sarkineti, an ancient site in the vicinity of Iberia's (the Caucasian Iberia's) first capital, Mtskhetha. But the most famous cultural treasure of the time is the metalwork in bronze, silver and gold, perhaps the most famous aspect of Georgian artistic heritage in an international perspective.

Jvari Church (586/587-604)

The Jvari Monastery holds great religious significance as it stands on the site where St. Nino, who converted Georgia to Christianity in the early 4th century, erected a large wooden cross. "Jvari" translates to "Cross" in English, reflecting the origin of the monastery. It was built in the 6th century, between 585 and 604 AD, by St. Nino's disciple, Monk Gabriel. It is often considered one of the earliest examples of a four-apsed church in the region.

The Jvari Church follows the traditional cross-in-square design common in early Christian Georgian architecture. It consists of a central square plan with a dome supported by four pillars or piers. However, Jvari is known for its distinctive four-apsed structure, which is relatively rare in Georgian architecture. Each apse faces one of the cardinal directions.

The exterior of the church is adorned with rich decorative elements, including carved stone reliefs and ornaments. These intricate details feature both Christian symbols and pagan motifs. Adjacent to the main church, there is a later-built free-standing bell tower that complements the architectural ensemble. The facades are decorated with various crosses, including the Georgian cross, which is a distinctive cross with grapevine decorations at the ends.

The strategic location of Jvari atop a rocky mountain provides a breathtaking panoramic view of the confluence of the Mtkvari and Aragvi rivers, as well as the town of Mtskheta. Jvari Monastery, along with the historical monuments of Mtskheta, has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1994.

The Jvari Church follows the traditional cross-in-square design common in early Christian Georgian architecture. It consists of a central square plan with a dome supported by four pillars or piers. However, Jvari is known for its distinctive four-apsed structure, which is relatively rare in Georgian architecture. Each apse faces one of the cardinal directions.

The exterior of the church is adorned with rich decorative elements, including carved stone reliefs and ornaments. These intricate details feature both Christian symbols and pagan motifs. Adjacent to the main church, there is a later-built free-standing bell tower that complements the architectural ensemble. The facades are decorated with various crosses, including the Georgian cross, which is a distinctive cross with grapevine decorations at the ends.

The strategic location of Jvari atop a rocky mountain provides a breathtaking panoramic view of the confluence of the Mtkvari and Aragvi rivers, as well as the town of Mtskheta. Jvari Monastery, along with the historical monuments of Mtskheta, has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1994.

Kakheti | კახეთი

Kakheti is the easternmost region of Georgia, bordered by Chechnya, Dagestan and Azerbaijan. It was an independent kingdom in the 15th c., and then came under Iranian rule from the 16th practically till the early 19th c., although in 1762 the Kakhetian Kingdom was united with the neighbouring Kingdom of Kartli under the king Heraclius II, that undoubtedly reinforced Georgian identity of this territory. Nonetheless, in 1801, the Kartli-Kakheti Kingdom was annexed to the Russian empire.

Ali und Nino26.07.2015

This couple of tailor's dummies adorning Batumi's seashore promenade may seem not particularly attractive at the first glance. Yet the sculpture by Tamara Kvesitadze is meaningful enough when put into movement: both figures perform a slow dance, periodically merging with each other. These are Ali and Nino, the heroes of the most famous Caucasian novel, published in Vienna in 1937. It is indeed a beautiful book, and made me reflect a great deal. Is the cross-cultural love story indeed at its center? I'm not sure. Perhaps it's all about civilization, and the complicated dance some people and peoples perform among and around its crucial concepts. The text actually opens upon a geography lesson, in a colonial school that represents in this instance the Russian dominion. The pupils are forced to decide themselves, to perform the "civilizational choice" that my colleague, Jan Kieniewicz, constantly talks about. And obstinately they try to avoid it. And obstinately, the history repeats itself, and Ali is shot by the Russians on the very same bridge where his grandfather died in similar circumstances. Currently, this text of quite unclear authorship is celebrated in Georgia and at the same time considered a kind of "Azerbaijani national novel". Who wrote it? Who is Kurban Said? A Jew? A baroness? In 2005, the doubt gave yet another best-selling book, Tom Reiss's The Orientalist: Solving the Mystery of a Strange and Dangerous Life. I do not doubt this German text has been written by a European hand. Yet it is very interesting indeed as a tentative of adopting the viewpoint of the colonized. I read this vision as falsification of a voice, of course, but still it is fascinating as such. As I said, the necessity of the choice is imposed, I don't believe it could emanate for the Caucasian subject himself or herself. The lovers know too much about identity, and they know they are the Orientals. Nino sees the things too clearly, opposing herself to the Persian harem lifestyle, and her condition of refugee makes such an opposition extremely untimely and improbable. The experience of shame is imposed at yet another moment, when Nino's horrified glance spots Ali among other Shiites during the festivities. Or rather, she is forced to share the horrified glance of a European ambassador, observing the flagellant procession. But on the other hand, the narration is by no means untrue. Typically for any Orientalizing fiction, the entanglement of truth and falsification is not to be resolved. The truth, once again, consists in the persuasive way of presenting the choice, the "either ... or" essentially alien to the Caucasian subject, as the oppression exerted by the Russian schoolmaster. The very same Russian schoolmaster that might have formed, one or two generations ago, also us, the Poles. And there is of course their own choice, tertium datur, against the imposed obligation of "civilizational choice". They chose each other, i.e. they chose the syncretism and synergistic development advocated by their Armenian middleman. Yet again, the Orientalizing fiction operates by stereotype: the Armenian middleman must betray them; having trusted him was Ali's mistake. The colonial principle divide et impera is reintroduced surreptitiously, and Ali is shown at the highest of his wolfish Oriental characteristics as he bites through his rival's aorta with bare teeth. Wild is the Oriental, this is the apparent conclusion. But still, having read this book, I stay in the belief that the Caucasian history illustrates first of all the danger of promoting the "civilizational choice". The colonial lore might present the incessant Caucasian warfare as endemic. Nonetheless I see the region as a space of entangled civilizational choices that leave no place for syncretism nor synergistic development. Each nationalism is moved not only by its own local energy, but also by the distant gravitation of a civilizational center: looking up to Russia, to Iran, and recently, again, to Europe. These are the gravitational forces that split the Caucasus apart. Perhaps similarly to the German-speaking author of Ali und Nino, I've come to the Caucasus with a pre-conceived idea: that of transcultural dimension. I've brought with me an abstract concept in demand of an exemplification. I hoped to confront my idea with local truths and local circumstances. Should the confrontation throw light on the limitations of my theory, or rather illuminate its margins? There is yet another ready-made question, that of Bernard Lewis: what did actually went wrong? In fact, I've come to the Caucasus not only to test my theory, but also tempted by the lasting fame of ancient intellectual and artistic centers of Georgia and Armenia. And the feeling is indeed that of a history that had ended. In those famous centers of arts and literacy I could hardly find a bookshop meeting my expectations or a collection to captivate me more than for a glance. It seems as if they didn't survive the Mongols. The caesura was so easy to observe in the Museum of Fine Arts at Tbilisi. They, Christians, seem to have perished in the same cataclysm that put an end to the finest layer of the Islamic civilization. Even the technique of cloisonne enamel had been lost for several centuries, before it reappeared quite recently as an industry of colorful accessories for the tourists. Yet there had been a Golden Age. As far as I could read and see their history in visual documents, the synergistic development existed at the very beginning. The expansion of the early Islam, and the Islamic conquest of the Caucasus, didn't put an end to the Christian culture of Georgia; by the contrary, created a fertile ground for it. The originality of the Golden Age in the 12th century appears at the intersection of the Persian influence and Christianity. Shota Rustaveli, putting Persian story into Christian verse, seems to give a good example of this. And the guide in the Tbilisian museum called my attention to the moment in which Persian roses occupy the place of the vine leaves and tendrils in the repoussé backgrounds. Plentiful exemplification of this synergistic development is to be found in architecture, enriched with geometrical aesthetics of Islam. The Golden Age is result of the refusal of "civilizational choice", refusal of admitting the condition of a periphery subdued to one center exclusively. I believe that the strategy of survival in such a place as the Caucasus is to keep a balance, even if I don't see clearly enough how could they possibly maintain it. Perhaps my transcultural humanities might serve them better than any other. Larger horizons, opening these valleys, fruitful superpositions instead of essentialist "civilizational choices" are requested. As individuals, people find these ways instinctively. Economically still very modest as they are across all the region, they do travel, they spend their holidays in Batumi, they look to the sculpture in its incessant movement, Ali and Nino in their dance of distance, approximation and merging. One day the engine shall break down, yet hopefully another day it shall be replaced again. |

Worship and exposition.

|