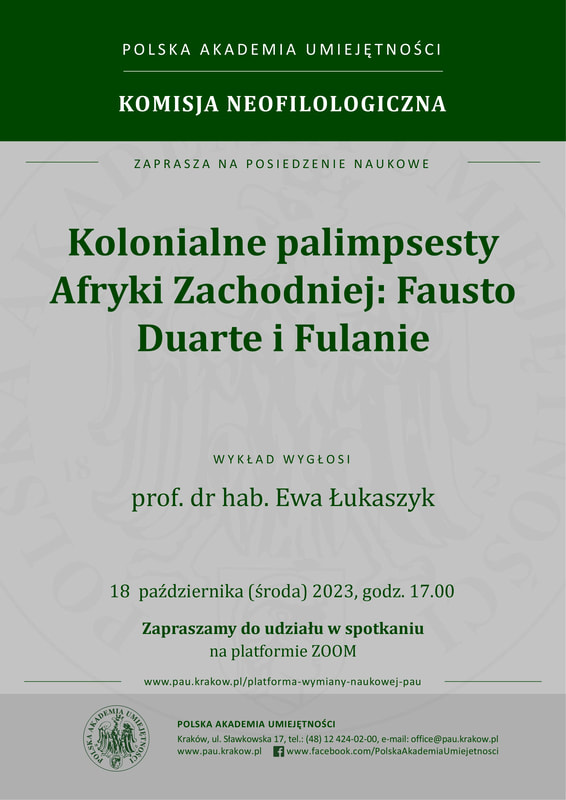

Representations of the Fulani world

in Portuguese colonial writing

The history of the Fulas is closely related to that of the Islamic penetration. Islam in West Africa dates back to the 12th-14th centuries and is related to the great Empire of Mali, created by Islamized Mandinka, a people originally from Upper Niger. At the beginning of the 14th century, Emperor Kankou Moussa immortalized himself on a pilgrimage to Mecca in which the caravan that accompanied him carried a quantity of gold that became legendary. In the phase of disintegration of the empire, the warrior Tiramakan Traore emerged, founder of the Kaabunké state on the plains of the High Coast of Guinea. The Fula moved from Bundo to the territory of Kaabú (Gabú) and settled in the Tumaná de Cima's region, accepted by the Mandingas as “guests”. At the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century, the Mandinka tried to dominate the animistic peoples, populating the banks of the Gambia. At that time, a social division was formed between the upper Islamic classes and the people dedicating themselves to the cult of ancestors. Until the 18th century, the Fula were under the domination of the Mandinga. The situation changed after the conquest of Kansala (1867) and the destruction of the kingdom of Kaabú. In the years 1868-1888, the Fula fought a holy war against the Beafada “infidels”, conquering the territory of Djoladú, renamed Forreá. Around 1885-1890, another important turning point was the conversion imposed on the soninqués, the balantas and the felupes. The holy war declared by the Fula Almamis involved pillage and the enslavement of animist peoples.

Throughout the colonial period, the Portuguese carried out some research in Guinea. António Carreira's monograph, Mandingas da Guiné Portuguesa, published in 1947, presented not only the Islamized Mandingas, but also the animist peoples: the soninke and the beafada – that is, the djolas according to the name most frequently used in international literature. However, there is a predilection for the Fula. Among the most important monographs, the volume Fulas do Gabú stands out, in which José Mendes Moreira, wanting to be an imitator of Delafosse, Tauxier and Arcin, brought together an attempt at “pullar” grammar, a list of photographs and several observations ethnographic studies on the living conditions and customs of the Fula. The problem of African literacy gains visibility. José Mendes Moreira attests that the Futa-fulas “have a vast written literature consisting of narratives of the heroic deeds and warlike endeavors of the conquerors of Futa-Djalom [...] in addition to translations of the Quran and political precepts. religious and social heritage inherited from the Arab and Arab-Berber” (Moreira, 1948, p. 95). In the part dedicated to material culture, Moreira observes that the Fula write “on sheets of paper or on planed boards with ink prepared by them and a wooden pen sharpened at the end which they call carã-bôl” (Moreira, 1948, p. 170 ). Later, he further clarifies that it is “marabu” paper (Moreira, 1948, p. 247), probably paper produced in West Africa according to traditional procedures of Eastern origin, without the need for import. He also reports several magical rituals related to writing: at the site of the founding of a new village, a piece of paper with a Quranic inscription is buried; to be successful in hunting, the hunter “greaves himself with a mèzina prepared with a herb called goli-goli [...] to which he also adds a piece of paper written with a verse from the Quran” (Moreira, 1948, p. 234). On the other hand, the Portuguese scholar outlines a classification of functions within the literate group that he describes as a “priestly class”: “1st – Ualio (a kind of prophet); 2nd – Karamokodjô (a type of doctor in Koranic theology); 3rd – Almúdo (simple reader of the Quran); 4th – Talibádjô (disciple, assistant)” (Moreira, 1948, pp. 234-235). Finally, Moreira speaks of “some marabou paper books, written in Arabic characters, where the origins of the tribe are narrated, the exploits of illustrious chiefs [...], the battles won [...], the wisdom of the karamokos and the fasts and virtues of the holy Muslim men” (Moreira, 1948, p. 247). However, to access the “tarika” (or "tarih" - history) of the Fulas, he employed a local informant, identified as “Mama N ́gari Djalfó, head of the Kamboré mosque” (Moreira, 1948, p. 264) who translates the text from Arabic to Creole. Only from this Creole version did Moreira write the text included in the monograph, which must therefore hide several errors and omissions. However, the text transmitted is quite curious. The Fulani's achievement, which begins with “the Turuban war” (1284 AH), is preceded by the narration of humanity's achievement since the creation of the world, covering several pre-Adamic generations, of less than a thousand years each (including the period of the primordial king Djimu). Only after a series of such periods does Baba Adaman appear. For a thousand years he lives in a paradisiacal space, until Allah makes him descend to earth in a place called Indi. His wife Auá descends, on the contrary, in Nadjidí, near Mecca. [...]

The scholarly effort to formulate an ethnohistory of West Africa was also led by Avelino Teixeira da Mota, who attempted to compare the information contained in Portuguese 16th century chronicles with the conclusions of French scholars, speaking during a very significant event that was the International Conference of West Africanists. organized in Bissau in 1947. [...]

Throughout the colonial period, the Portuguese carried out some research in Guinea. António Carreira's monograph, Mandingas da Guiné Portuguesa, published in 1947, presented not only the Islamized Mandingas, but also the animist peoples: the soninke and the beafada – that is, the djolas according to the name most frequently used in international literature. However, there is a predilection for the Fula. Among the most important monographs, the volume Fulas do Gabú stands out, in which José Mendes Moreira, wanting to be an imitator of Delafosse, Tauxier and Arcin, brought together an attempt at “pullar” grammar, a list of photographs and several observations ethnographic studies on the living conditions and customs of the Fula. The problem of African literacy gains visibility. José Mendes Moreira attests that the Futa-fulas “have a vast written literature consisting of narratives of the heroic deeds and warlike endeavors of the conquerors of Futa-Djalom [...] in addition to translations of the Quran and political precepts. religious and social heritage inherited from the Arab and Arab-Berber” (Moreira, 1948, p. 95). In the part dedicated to material culture, Moreira observes that the Fula write “on sheets of paper or on planed boards with ink prepared by them and a wooden pen sharpened at the end which they call carã-bôl” (Moreira, 1948, p. 170 ). Later, he further clarifies that it is “marabu” paper (Moreira, 1948, p. 247), probably paper produced in West Africa according to traditional procedures of Eastern origin, without the need for import. He also reports several magical rituals related to writing: at the site of the founding of a new village, a piece of paper with a Quranic inscription is buried; to be successful in hunting, the hunter “greaves himself with a mèzina prepared with a herb called goli-goli [...] to which he also adds a piece of paper written with a verse from the Quran” (Moreira, 1948, p. 234). On the other hand, the Portuguese scholar outlines a classification of functions within the literate group that he describes as a “priestly class”: “1st – Ualio (a kind of prophet); 2nd – Karamokodjô (a type of doctor in Koranic theology); 3rd – Almúdo (simple reader of the Quran); 4th – Talibádjô (disciple, assistant)” (Moreira, 1948, pp. 234-235). Finally, Moreira speaks of “some marabou paper books, written in Arabic characters, where the origins of the tribe are narrated, the exploits of illustrious chiefs [...], the battles won [...], the wisdom of the karamokos and the fasts and virtues of the holy Muslim men” (Moreira, 1948, p. 247). However, to access the “tarika” (or "tarih" - history) of the Fulas, he employed a local informant, identified as “Mama N ́gari Djalfó, head of the Kamboré mosque” (Moreira, 1948, p. 264) who translates the text from Arabic to Creole. Only from this Creole version did Moreira write the text included in the monograph, which must therefore hide several errors and omissions. However, the text transmitted is quite curious. The Fulani's achievement, which begins with “the Turuban war” (1284 AH), is preceded by the narration of humanity's achievement since the creation of the world, covering several pre-Adamic generations, of less than a thousand years each (including the period of the primordial king Djimu). Only after a series of such periods does Baba Adaman appear. For a thousand years he lives in a paradisiacal space, until Allah makes him descend to earth in a place called Indi. His wife Auá descends, on the contrary, in Nadjidí, near Mecca. [...]

The scholarly effort to formulate an ethnohistory of West Africa was also led by Avelino Teixeira da Mota, who attempted to compare the information contained in Portuguese 16th century chronicles with the conclusions of French scholars, speaking during a very significant event that was the International Conference of West Africanists. organized in Bissau in 1947. [...]

|

The Fula were also portrayed in the novelistic works of Fausto Duarte, Auá and A Revolta. Although Fausto Duarte was born in the Cape Verde Islands, he spent almost his entire professional career in Portuguese Guinea, or today's Guinea-Bissau, as a colonial administrator. Due to these professional circumstances, he was able to observe the lives of different ethnic groups and tried to turn it into literature based essentially on the patterns of Portuguese realistic-naturalistic school. On the other hand, he tried to refresh this somewhat outdated literary formula referring to the French models of the time, that he perceived as a fashion for "Negritude" ("Paris adorou os negros, e as glórias apontadas pela metrópole francesa são cobiçadas pelo mundo civilizado" (Duarte, 1934b, p. 8) - I apologize for this politically incorrect expression, but Duarte, as a colonial author, is thoroughly politically incorrect at almost every step).

As a Caboverdian, he wished to be considered, in a sense, as the Portuguese René Maran - the first black writer to win the Goncourt Prize in France (in 1921). This Martinique-born writer was a French colonial administrator employed in what was then French Equatorial Africa - Fausto Duarte may have felt that this biography - birth on the islands, later service in colonial structures - resembled his own, so tried to imitate Maran's path to literary success. And indeed, in 1934, Fausto Duarte also won at least what was available in his native metropolis, i.e. the first prize in the colonial literature competition for his novel titled Auá ("Eve"). [...] At the time when Fausto Duarte was trying to forge his vision of African literature and was writing his own African novel (Auá is subtitled "novela negra"), the content, scope and message of Fula writing were still unknown. However, it was fascinating to discover that they wrote at all, that they were so interested in writing, that they had their own historical memory. This was a revelation at the time. And perhaps it was under the impact of this revelation that Fausto Duarte made the construction of the native hero in Auá completely different from the colonial paradigm. Malam is presented as an active, self-standing and self-aware protagonist, rather than acolyte of any white figure [...]. |

Mandinga and Fula ethnohistory between the Islamicate and colonial world

Currently, my interests in Islamicate intellectual history are focused on West Africa in the colonial period (19th-20th century).