Amazigh cultural emancipation1. Historical background

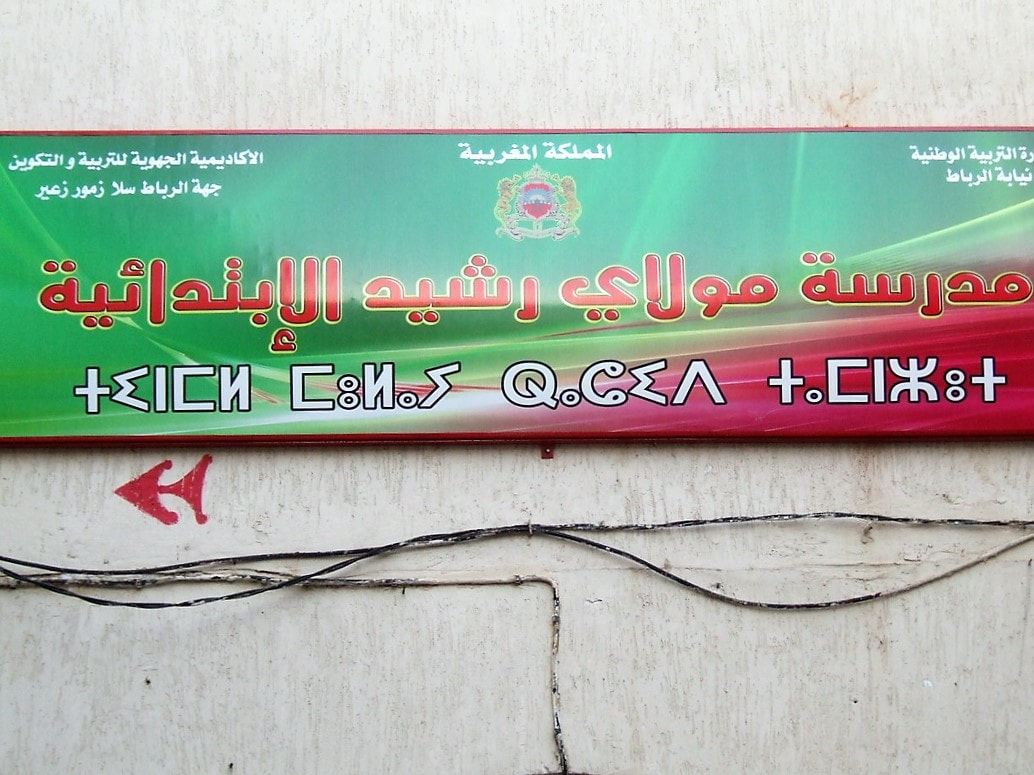

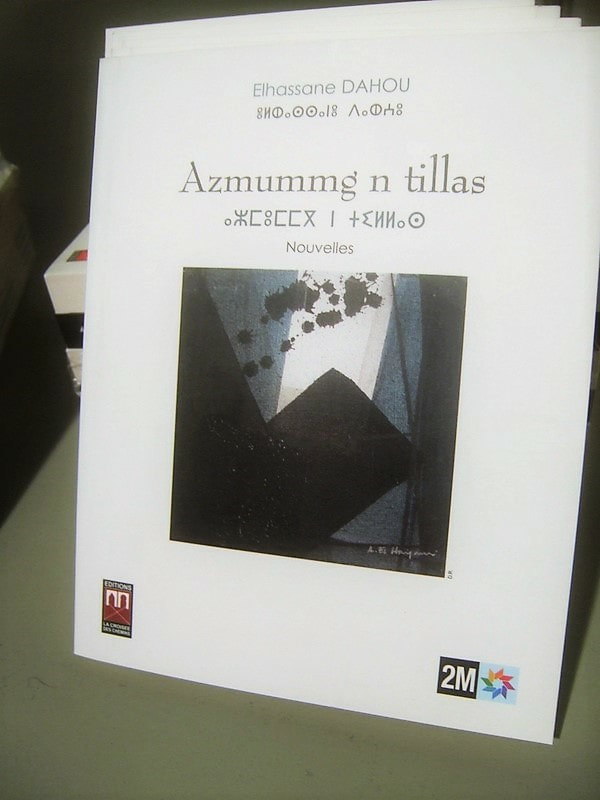

The first thing we should keep in mind is that Amazigh identity is something extremely old. It can be conceptualized as an aboriginal identity of the southwestern Mediterranean. The history of Imazighen is contemporary to ancient Egypt, Carthage, and the Roman Empire. The beginnings of the scriptural tradition are equally ancient, starting with the so-called libyco-berber script, which was originally an abjad used by the peoples of the desert, such as the Tuaregs. Such is the origin of the contemporary Tifinagh or rather the neo-Tifinagh considered by many as the “proper” way of writing in Amazigh today (I will return to this point later on). This is thus an identity that had already well-established traditions at the moment of the Islamic expansion in the 7th century A.C. Despite the frictions, one might claim that overall the Berbers found their due place and their cultural expression in the Islamic state organisms of the region. The acme of the Berber culture may be identified with the reformist movements in Islam finding their political expression in the Almohad Empire (1121-1269). The next centuries brought a progressive Arabization and the ossification of the Berber peculiar religious culture. Nonetheless, Berber separatism survived and was actively exploited by the colonial rulers of the Maghreb, using the well-known strategy of Divide et impera (“divide and rule”). The post-colonial state of King Muhammad V searched for a national identity connected to the unifying power of the Arabic language. The Berber identity was thus placed at the margin of the process and the political dangers of the Berber separatism had been overestimated, which can be easily understood given the unstable situation in Algeria. This is why the demands for cultural emancipation during the last decade of the 20th century encountered extremely inflexible responses from the government and the king. The situation changed with the advent of the new ruler, Muhammad VI, who recognized the legitimacy of the Berber claims. 2. Political solutions In the new constitution, Amazigh was recognized as the 2nd official language of the state. During the first years of the new millennium, the Berber language found its place both in the educational system and the Moroccan academia. To a certain degree, we can admit that all the necessary steps have been taken to guarantee linguistic normalization. Amazigh, as the official language, is taught to all the inhabitants, including those without direct Berber ancestors. A special institution (IRCAM) has been created under royal patronage to promote research concerning all the aspects of the Amazigh culture and to foster its development. Nonetheless, the existing situation is not the ideal one. Still, there is a lot of widespread resistance towards the cause of the Amazigh language. People, including the parents of the schooled children, see the class of Amazigh as a useless chore, diverting the attention of their children from more useful subjects, including French and English. In the context of the Moroccan educational reality, leaving no margin for improper allocation of scarce resources, Amazigh is seen as a useless expenditure offering no future to anybody, including the students of the first curricula in Amazigh culture that has been created in all or nearly all universities of the country (many of them encountered no employment). Seemingly, the revitalization process has led to a stalemate. 3. Revitalization as a modernizing project In my opinion, the most interesting aspect of the ongoing process is the response of the activists and the promoters of the Berber identity to this stalemate. Here I pass to the examination of the main corpus of my research, i.e. the essays of cultural criticism published in French during the last 3-4 years. In my opinion, the choice of French as the language of expression is not accidental in this context. To some degree, it is a language of the battle, supporting the Berber identity at the moment in which the Amazigh prose is still incipient (the majority of the adult population simply don't read it, even if some may communicate in Amazigh orally at the everyday life level). The main advantage of French is simply that of not being Arabic. Significantly, it is no longer a “post-colonial” language, but rather a neutral one that appears as a useful instrument of support for the identity cause and a tool of communication with the external world. That is an important aspect, of preventing the isolation of the Berber cause. A limited usage of Spanish is also to be noticed, for quite similar reasons; the linguistic normalization that took place in Spain after the end of the dictatorship of Franco is also a ready-made paradigm. On the other hand, the Berber identity movement relies importantly on the Moroccan diaspora and on the inspirations coming from different European countries in which the linguistic questions had been solved. The essays on cultural criticism I've studied accentuate first of all the necessity of creating a new Amazigh culture. The proposal is to go beyond the first steps which consisted mainly in collecting the oral patrimony. Two key terms in Amazigh, treated by the authors as untranslatable, call my attention: asgudi and taskla. The first term, meaning literally “accumulation”, refers to the process of gathering the patrimony of the oral culture. The stability of the written text is meaningfully contrasted with the perishable condition of the spoken word. The writing brings thus the promise of enrichment by gathering and accumulation the cultural content, just as the cereals or other provisions are stocked in a cellar. It's clear that in the first moment, the fascination with writing as such was intense, sometimes even excessive and grotesque. Apparently, the blatant lack of an established norm and orthography was not considered as an obstacle. The problem of the Amazigh script is still unsolved. At the level of declarations, as it seems, the Tifinagh is considered the most appropriate form of writing. Nonetheless, I could find no book written entirely in Tifinagh. Most publications have just the title and eventually the name of the author written in the traditional script. The content of the book is printed either in Latin or in Arabic characters. The tifinagh, as it seems to me, has a representative function of a monumental script. Its characteristic graphic form appears in trilingual official inscriptions in institutions public buildings, and other similar contexts. The Tifinagh script seems to be rather an insigne of identification than a practical way of writing. This is also a quite curious cultural function that I associate with the ancestral understanding of writing as a form of magic. Nonetheless, the core of the Amazigh cultural project seems to be quite the reverse of all forms of ancestral culture. What is postulated with insistence is the creation of a “taskla”, sometimes translated by such expression as “emergent literature” or “neo-literature”. The word is a neologism defined in opposition to the ancient Amazigh word for literature, “lmazghi”. The aim of this new Amazigh literary creation is, as I suggested, that of breaking the stalemate between the dominant Arabness and the Berber culture that received political rights but remained nonetheless in a minor condition. The Amazigh language and culture are taught at school and at the university, but as the Berbers themselves recognize, there is nothing in them that would really justify the discussion and the scholarly analysis. This culture is seen by the Imazighen themselves as nonexistent. It exists potentially, as a project that requires a realization. Somehow, as they see it, the proper Berber culture is located in the future. As a foreign observer, I must recognize this may be an extremely mobilizing prospect in which the minor community establishes itself indeed as an important element of the national cultural landscape. At the present moment, Imazighen feel they are just a burden for the national educational system. But there is an idea of how to pay back this investment transforming the Berber element into one of the leading forces of the nation. Arguably, such a prospective Amazighity is indeed orientated towards the future in a better, more energetic way than other elements of the Moroccan cultural landscape. Amazigh identity, instead of looking back into the glorious past, is transformed into a motor of change. This is a very positive style of solving the problem of a minor identity.

|

|

"Asgudi i taskla: przejście od oralności do pisma i nowa literatura w poszukiwaniach tożsamości marokańskich Berberów" ["Asgudi and Taskla. The transition from orality to literacy and the emergent literature in the search for Amazigh identity in Morocco"], Przegląd orientalistyczny, nr 1-2/2014, p. 89-98. ISSN 0033-2283

| ||||||||

"L'identité amazighe et la langue française. Autour de l'auto-traduction du roman Le Pain des corbeaux par Lhoussain Azergui" ["Amazigh identity and French language. On auto-translation of the novel Le Pain des corbeaux by Lhoussain Azergui"], Romanica Cracoviensia, nr 13/2013, p. 207-216. ISSN 1732-8705; ISBN 978-83-233-3479-8 e-ISSN 1689-002

http://www.ejournals.eu/Romanica-Cracoviensia/Tom-13/Numer-3/art/1629/

The main problem discussed in the article is the meaning of the decision taken by Lhoussain Azergui who, after having engaged in the process of revitalization, finally opted by translating into French his novel originally written in Amazigh. The phenomenon of the emergent Amazigh literature can be understood in the perspective of transcolonial renegotiation of Maghrebian identities. With Azergui, it enters a new field of experimentation, when the linguistic fidelity is broken to let the writer confront himself with a major literary language. It is a “betrayal with a promise of return” that can lead to a new stage in the development of Amazigh culture. Azergui’s novel justifies internally the option of translation. Its main subject is the necessity of crossing the borders of traditional mentality. The hero, a journalist leaving the prison, finds no place in his own community due to the ancestral believes considering writing as a magical gesture. The traditional culture finds the hero guilty of supreme transgression, which is punishable by death. The intellectual rejected by his own community has no other option than to seek alliances in the outside world, hoping to efface the frontiers between the local and the global.

http://www.ejournals.eu/Romanica-Cracoviensia/Tom-13/Numer-3/art/1629/

The main problem discussed in the article is the meaning of the decision taken by Lhoussain Azergui who, after having engaged in the process of revitalization, finally opted by translating into French his novel originally written in Amazigh. The phenomenon of the emergent Amazigh literature can be understood in the perspective of transcolonial renegotiation of Maghrebian identities. With Azergui, it enters a new field of experimentation, when the linguistic fidelity is broken to let the writer confront himself with a major literary language. It is a “betrayal with a promise of return” that can lead to a new stage in the development of Amazigh culture. Azergui’s novel justifies internally the option of translation. Its main subject is the necessity of crossing the borders of traditional mentality. The hero, a journalist leaving the prison, finds no place in his own community due to the ancestral believes considering writing as a magical gesture. The traditional culture finds the hero guilty of supreme transgression, which is punishable by death. The intellectual rejected by his own community has no other option than to seek alliances in the outside world, hoping to efface the frontiers between the local and the global.

| |||||||