what is Czech literature?

Czech literature is a fascinating one, underestimated, as I believe, in the European context. Richer than expected, striking and fresh, ironic, humoristic, incisive. It has also an unsuspected element of religiosity, a mystical component.

I will write more about it soon.

I will write more about it soon.

I have readTomáš Zmeškal, Milostný dopis klínovým písmem | Love Letter in Cuneiform Script (2008)

Michal Viewegh, Povídky o manželství a sexu (1999) Milan Kundera, Nesnesitelná lehkost bytí (1984) Franz Kafka, Der Prozess | The Trial (1925), Das Schloss | The Castle (1926), Amerika (1927), Die Verwandlung | The Metamorphosis (1915), In der Strafkolonie | In the Penal Colony (1919) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have written... nothing ...

|

under the spell of Czech language

I have dreams, plans for when I settle in the Netherlands for good, with a decent house and a stable employment. I would like to buy more books in Czech. I have learned the language, at least enough to read, just for the sheer fun of it; for someone speaking Polish it is not such a great exploit; it seems a constant source of absolutely mind-boggling linguistic humour; at least at a certain stage of my life I grew a palate for such things. What is more, Czech Republic, together with Romania, are my favourite countries in Central and Eastern Europe. In spite of their cuisine.

This is thus a shame that I have read so few Czech literature, and usually in translation. I've read Kundera in French when I was a student; I took it from the library of the local Alliance Francaise centre in Lublin. Other things in Polish. But it must be an adventure to read Jaroslav Hašek's Szwejk right in its proper, picturesque language. Unfortunately, books in Czech Republic tended to be relatively expensive, and they are not always easy to find in university libraries.

There are nonetheless some Czech things in my Polyglot Library, for instance Poslední stupeň důvernosti (The Ultimate Intimacy) by Ivan Klíma. And the best of all, Milostný dopis klínovým písmem by Tomáš Zmeškal, a son of a Czech and a Congolan. His delving in the times of communist oppression makes me remember Kundera's Unsupportable lightness of being, and what remains is a love letter written in Cuneiform and the background of the bygone academic excellence, when such things were studied and taught in Prague.

I even have a history of Czech literature, by Zofia Tarajło-Lipowska. I just miss my Dutch home, outside the Mitteleuropa, to read all this. Somehow, this is a kind of literature – like a lot of Romanian and Hungarian one as well – that one feels better to read without, not within. Just like you enjoy reading horrors when you are out of danger.

This is thus a shame that I have read so few Czech literature, and usually in translation. I've read Kundera in French when I was a student; I took it from the library of the local Alliance Francaise centre in Lublin. Other things in Polish. But it must be an adventure to read Jaroslav Hašek's Szwejk right in its proper, picturesque language. Unfortunately, books in Czech Republic tended to be relatively expensive, and they are not always easy to find in university libraries.

There are nonetheless some Czech things in my Polyglot Library, for instance Poslední stupeň důvernosti (The Ultimate Intimacy) by Ivan Klíma. And the best of all, Milostný dopis klínovým písmem by Tomáš Zmeškal, a son of a Czech and a Congolan. His delving in the times of communist oppression makes me remember Kundera's Unsupportable lightness of being, and what remains is a love letter written in Cuneiform and the background of the bygone academic excellence, when such things were studied and taught in Prague.

I even have a history of Czech literature, by Zofia Tarajło-Lipowska. I just miss my Dutch home, outside the Mitteleuropa, to read all this. Somehow, this is a kind of literature – like a lot of Romanian and Hungarian one as well – that one feels better to read without, not within. Just like you enjoy reading horrors when you are out of danger.

Prague

|

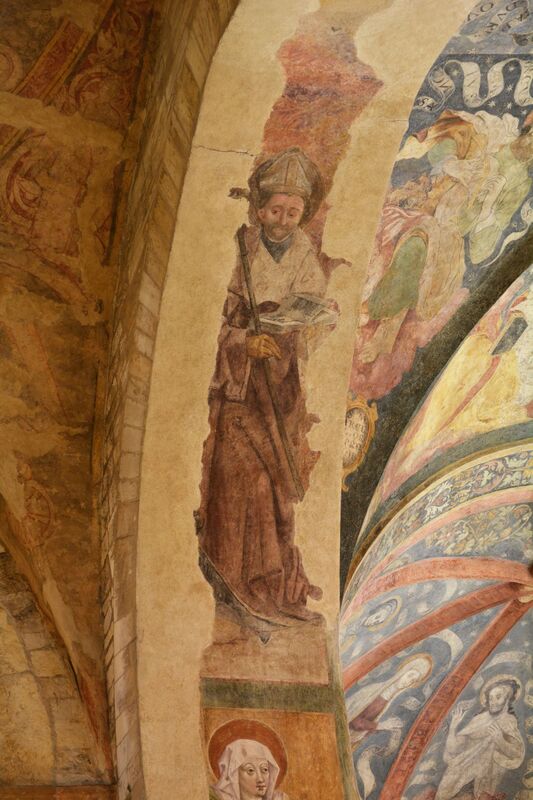

Prague is one of those dear cities of Mitteleuropa that I could visit very early in my life, perhaps around 1985, when it was still quite a surprise for me that chocolate was available in any store (in Poland, chocolate was still to be bought exclusively with food stamps). Certainly, I returned there many times, in 2000, 2016 and 2017, till the point of falling under the charm of the Czech language, so amusing to my ear as if it were a constant parade of puns and funny ways of dubbing things.

Together with Lisbon, Prague used to be commonly regarded as an utterly poetic place; was it for a resonance of Kafka and Pessoa in the popular imagination? Be as it may, there exist advanced schools for taking pictures of these cities (Prague even more than Lisbon). Myself, I could never achieve the level of sophistication in any of them. Perhaps my eye is not fresh enough, or I don't have sufficient patience to get up early enough to catch the bridge clothed in nothing but the fog. |

my summer readings in Czech literature

anarchism & humour

It's August. I'm making order in my rebellious library, that seems to grow bigger with every box of books that I expediate to the foundation supporting countryside libraries, and more chaotic with every attempt at exploring it. I'm thinking what to do with my Polish translations of Czech literature, not very prestigious volumes that should be one day replaced with good, original editions. Since I'm learning Czech!

Meanwhile, I go through a collection of short stories and humorous sketches of Jaroslav Hašek; hardly to be called a critical edition; I can't even identify the original source of those texts; apparently, Hašek wrote some 1,200 such texts, dispersed in various publications. The paper of my booklet is yellow, and I feel the translation must be much less funny than the original. It is a shadow of a book. Such books satisfied me for a long time, when I hoped not to have the best, in any domain; but they don't satisfy me any longer. I want precision, I want the original, I want an edition that really deserves to be collected.

Meanwhile, as I read this one before packing it for the countryside libraries, I try to understand the ambivalences of Czech literature, and of Hašek himself. Those humorous short stories depict the Austro-Hungarian empire with its peculiar picturesque: its littleness, its bureaucracy, its proliferation of subaltern condition, its pyramidal structures of subservience that dominate the lives of individuals. This is how we usually imagine the Czechs, at least in Poland. As settled, unimaginative people drinking a lot of beer and consuming a particularly heavy cuisine. No wonder that the writer glosses on the impossibility of running away, like in that story in which a junior employee Tenkrat is caught in an ingenious net of intrigue forcing him to marry his boss' unattractive daughter.

Unable to date precisely the stories from my imperfect Polish edition, I wonder if the Austro-Hungarian empire still existed when Hašek wrote those things; or they were some sort of exercise in nostalgia, just like The Good Soldier Švejk, that was written after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian world, when that old life did not matter any longer, anyway, and it had no importance whatsoever if Švejk was enthusiastic to fight for it or not really keen to do so. Meanwhile, many of those things seem to be inspired by the writer's own military service.

Hašek was a soldier, and an anarchist, and a Bolshevik, later on, in Russia. Some say he was closely connected to Trotsky; some say he was a secret agent in Mongolia. As for an unfit, obese man Hašek was at the time, these are rather surprising adventures. Some say he even learned Chinese to establish connections with Chinese revolutionaries. And I think something like this happens all the time, a silver lining of something very imaginative, very unusual constantly piercing through the regularity and normalcy of Czech life.

By the way, it is not unusual, as I think about it now, to see anarchism and humour get together in European letters. I just think about A man who was Thursday, by G.K. Chesterton. Is anarchism something essentially unserious, as Chesterton assumed, making his anarchist secret council entirely composed of secret detectives? Or on the contrary, as Hašek assumes, something essentially unserious is the empire, with its pyramidal structures, hierarchies, procedures, incompetent ministers, aristocrats infested with tapeworms?

Jaroslav Hašek, Tasiemiec Księżnej Pani i inne opowieści, trans. Stefan Krysiak, Kraków, 2009.

Kraków, 2.08.2021.

Meanwhile, I go through a collection of short stories and humorous sketches of Jaroslav Hašek; hardly to be called a critical edition; I can't even identify the original source of those texts; apparently, Hašek wrote some 1,200 such texts, dispersed in various publications. The paper of my booklet is yellow, and I feel the translation must be much less funny than the original. It is a shadow of a book. Such books satisfied me for a long time, when I hoped not to have the best, in any domain; but they don't satisfy me any longer. I want precision, I want the original, I want an edition that really deserves to be collected.

Meanwhile, as I read this one before packing it for the countryside libraries, I try to understand the ambivalences of Czech literature, and of Hašek himself. Those humorous short stories depict the Austro-Hungarian empire with its peculiar picturesque: its littleness, its bureaucracy, its proliferation of subaltern condition, its pyramidal structures of subservience that dominate the lives of individuals. This is how we usually imagine the Czechs, at least in Poland. As settled, unimaginative people drinking a lot of beer and consuming a particularly heavy cuisine. No wonder that the writer glosses on the impossibility of running away, like in that story in which a junior employee Tenkrat is caught in an ingenious net of intrigue forcing him to marry his boss' unattractive daughter.

Unable to date precisely the stories from my imperfect Polish edition, I wonder if the Austro-Hungarian empire still existed when Hašek wrote those things; or they were some sort of exercise in nostalgia, just like The Good Soldier Švejk, that was written after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian world, when that old life did not matter any longer, anyway, and it had no importance whatsoever if Švejk was enthusiastic to fight for it or not really keen to do so. Meanwhile, many of those things seem to be inspired by the writer's own military service.

Hašek was a soldier, and an anarchist, and a Bolshevik, later on, in Russia. Some say he was closely connected to Trotsky; some say he was a secret agent in Mongolia. As for an unfit, obese man Hašek was at the time, these are rather surprising adventures. Some say he even learned Chinese to establish connections with Chinese revolutionaries. And I think something like this happens all the time, a silver lining of something very imaginative, very unusual constantly piercing through the regularity and normalcy of Czech life.

By the way, it is not unusual, as I think about it now, to see anarchism and humour get together in European letters. I just think about A man who was Thursday, by G.K. Chesterton. Is anarchism something essentially unserious, as Chesterton assumed, making his anarchist secret council entirely composed of secret detectives? Or on the contrary, as Hašek assumes, something essentially unserious is the empire, with its pyramidal structures, hierarchies, procedures, incompetent ministers, aristocrats infested with tapeworms?

Jaroslav Hašek, Tasiemiec Księżnej Pani i inne opowieści, trans. Stefan Krysiak, Kraków, 2009.

Kraków, 2.08.2021.