what is Moroccan literature?

This is the question that a doctor asked me once, in France. He was making a USG scan of my thyroid gland and probably he needed me either to speak or to relax, so he asked me what I was doing. I told him about my research project involving Moroccan writers. "Oh, is there Moroccan literature?," he asked. "I've heard about Algerian one, but I didn't know there is also Moroccan."

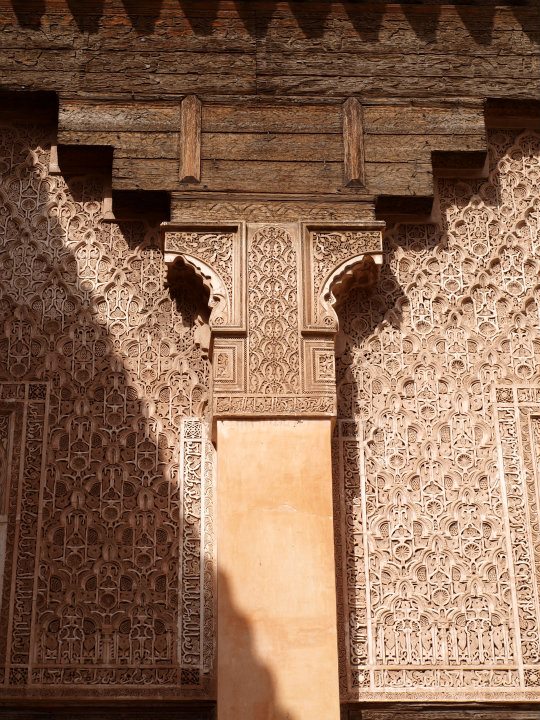

Oh yes, there is. The literature in Morocco can be traced back to the Antiquity, and associated either with Latin or with the autochthonous languages of the Mediterranean, of which the Amazigh and other Berber tongues, written in a peculiar Libyco-Berber script. And later on, there is of course the great era of the Arabic literature, in which Morocco was making one cultural area with the Iberian Al-Andalus, a great focus of intellectual and literary culture.

This is why I say many, many things happened before the Francophone era. Nowadays, the literary culture is double and triple, divided between the writing in French, Arabic and Amazigh.

Oh yes, there is. The literature in Morocco can be traced back to the Antiquity, and associated either with Latin or with the autochthonous languages of the Mediterranean, of which the Amazigh and other Berber tongues, written in a peculiar Libyco-Berber script. And later on, there is of course the great era of the Arabic literature, in which Morocco was making one cultural area with the Iberian Al-Andalus, a great focus of intellectual and literary culture.

This is why I say many, many things happened before the Francophone era. Nowadays, the literary culture is double and triple, divided between the writing in French, Arabic and Amazigh.

I have readLeila Slimani, Sex et mensonges. La vie sexuelle au Maroc (2017)

Lhoussain Azergui, Le pain des corbeaux (2013) Abdellah Taïa, Une mélancolie arabe (2008) Fatéma Mernissi, Rêves des femmes Tahar Ben Jelloun, La Réclusion solitaire (1976), Moha le fou, Moha le sage (1978), Sur ma mère (2008) Driss Chraïbi, Un monde à côté (2001), Une enquête au pays (1981), Civilisation, ma mère!... (1972), Les Boucs (1956) Paul Bowles, Let It Come Down (1952) Georges Montbard, A Travers le Maroc. Notes et Croquis d'un Artiste (1886) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have writtenLe ruban de Möbius. Pour un modèle topologique de la continuité créatrice dans le monde méditerranéen

L'identité amazighe et la langue française. Autour de l'auto-traduction du roman Le Pain des corbeaux par Lhoussain Azergui Asgudi i taskla: przejście od oralności do pisma i nowa literatura w poszukiwaniach tożsamości marokańskich Berberów Od Ogrodu kochanków Ibn Qajjima al-Dżawzijji do arabszczyzny transkulturowej. Projekt restytucji języka intymnego w pisarstwie Fatemy Mernissi i jego kontynuacje |

|

Vertical Divider

|

A travers le Maroc

Et en entendant dans le calme des nuits lumineuses et parfumées ces sons étranges, ces mélopées primitives, ces mille bruits divers, si particulièrement caractéristiques, des villes de l'Orient; en respirant cette atmosphère arabe si voluptueusement troublante, où les senteurs suaves et pénétrantes des grandes étendues vierges viennent se mêler et se fondre avec l'odeur âcre des aromates, la puanteur des charognes laissées sur les chemins, les émanations fortes des bêtes, tout notre être tressaille, surpris par toutes ces choses inaccutumées, se détend, amolli et comme engourdi par les subtiles effluves. On se sent envahi par une sorte de torpeur irrésistible, de grande lassitude de l'esprit où tous les sentiments, assouplis, effacés, éteints, sombrent en une sensation intense de repos complet, de bien-être absolu. (p. 100)

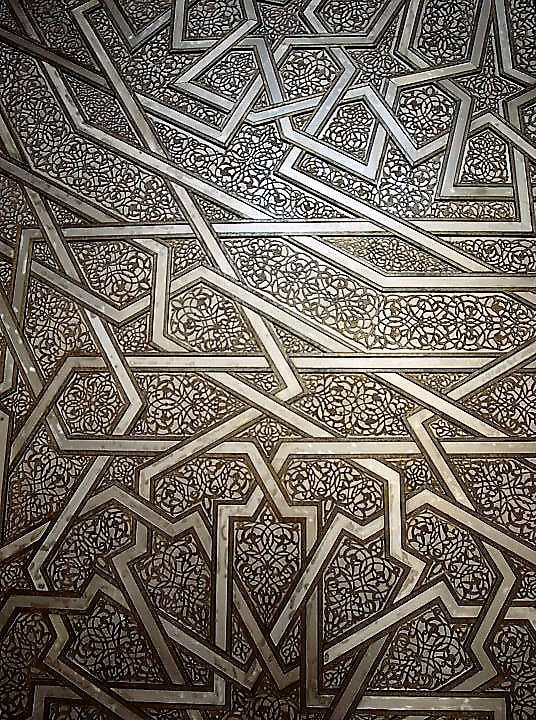

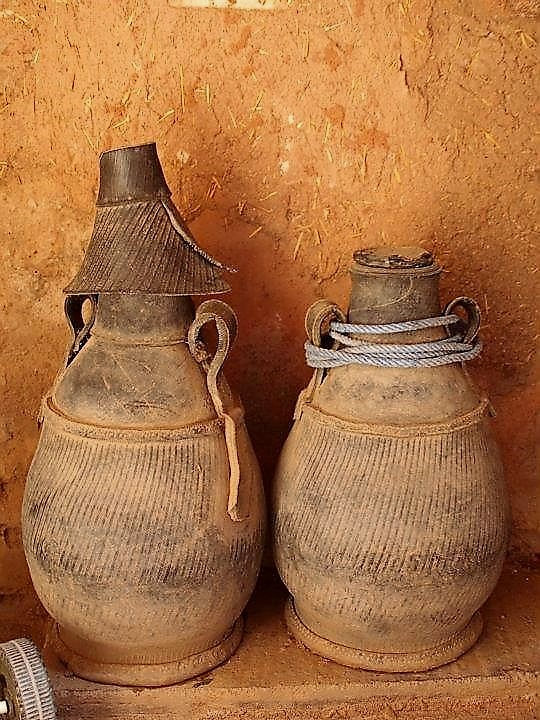

A facsimile edition of the travel book of Georges Montbard, or Charles Auguste Loye (1841-1905) who chose this pseudonym for his artistic life, takes me back to one of the countries I love most. Even if the book is shallow, superficial, ordinary, both in its verbosity and the quality of the sketches illustrating it. Montbard did not pretend much in his artistic destiny; he was an illustrator and caricaturist working with various journals and newspapers of his time, in France and Great Britain. Apparently, his Moroccan volume recently brought back to the readers by the Editions Frontispice, was not a very well known one; he seems to be remembered in the first place for his Egyptian travels; anyway, those things are available nowadays in the digital archives. I would say that Montbard brings us back to the 19th-century beginnings of tourism, and makes us muse on the superficiality inscribed in the European concept of pleasure travel since its beginnings, two centuries ago. His journey is not a grand tour; he does not travel in order to learn and does not pretend to know much about the world he describes and depicts, although one of his English compagnons already carries a camera, cet espion maudit, à la fois myope et presbyte, voyant faux à travers l'arragement compliqué de ses lentilles concaves et convexes (p. 168); there is a curious deprecation that he launches, over a coupe of pages, against this new medium that would have such a glorious future. During his peregrination in the northern part of Morocco, started and finished in the port of Tangier, the picturesque is what Montbard is after, both in the landscape and in the people he encounters: Moors, countryside girls, the black population that seems over-represented in his depiction. Even as he reaches the Roman ruins of Volubilis, he finds little place for historical or erudite digressions. He is a sensationalist, to put it this way, an empty subject carrying no knowledge, aspiring to no insight, and open to perception through all his senses. The book is full of things he saw, landscapes, vegetation, weather, but also sounds and smells, calls of muezzins, stinking dogs and donkeys. He travels through the land inebriated in perception, reasoning little, and bringing little of what might eventually have an influence on the views of his readers. Undoubtedly, it is a piece of colonial literature, with few compliments paid to the subaltern who occasionally let their lice fall right onto immaculate pages of the artist's sketchbook. There is no political correctness in the way he treats the Jews, the Negroes and, last but not least, the Moors themselves. The traveller is intrusive and ready to make a good use from his influence and dominant position, appealing for more than just the hospitality of the inhabitants; if sometimes he pays for the food he eats and the service he recieves, it is just as a way of being kind and polite; for the rest, he takes the country as something that is due to him and his companions: nous avons une lettre de recommandation de Si-Torrès, le ministre des Affaires étrangères du Maroc, résidant à Tanger. Nous possédons aussi une lettre du Sultan, laquelle nous donne droit à la "mouna" et aux égards des pachas, sheiks, kaids et autres fonctionnaires de l'empire, qui répondent de nos existences sur leur tête. Nous préférons, toutefois, payer les vivres que les habitants nous apportent et notre kaid est chargé de leur en régler le montant (p. 141). Meanwhile, this intruding subject has little comprehension, and no respect, to whatever might be hold sacred in the local eyes. Holiness is yet another part of the picturesque, and as such, everything has similar value: the graves of local saints, as well as the storcks, are sacred because of some ancient superstition (leurs corps contiennent les âmes de leurs ancêtres, lesquels vivaient autrefois dans de grandes îles par delà l'Océan, et qui sous cette forme reviennent pour les protéger; p. 80). For the rest, the travellers suffer from spleen, and they find in hunting whatever they miss in cultural perspicacity (on a fait des hécatombes de perdrix; p. 139). Montbard finds everything in the convenient state of dilapidation and disrepair; poverty and ruins are picturesque; they occupy the eye of this early tourist. He would like to add more cruelty and pathos to his Oriental vision; this is why he is keen to visit prisons wherever he goes. But for a long time it seems that the only result of his search for shock, abjection and delight would be pieces of meat oozing blood on the souk. Till finally, in the kasba of Meknes (written Méquinez in the book), he encounters the very thing he came for: Au-dessus de l'entrée, des crocs en fer sont solidement fixés. Après chaque révolte de tribus, les chefs des rebelles précipités du haut des créneaux, avec une adresse cruelle, s'enganchent sur ces pointes sinistres, où ils restent exposés comme un example terrible de la tout-puissante justice du Sultan, et les oiseaux du ciel, tandis qu'ils respirent encore, viennent arracher les yeux de leurs orbites et déchirent leurs membres pantelants. Leurs cadavres restent suspendus là et les chairs putréfiées se détachent et tombent en lambeaux dégoûtants que les chiens dévorent le jour et les chacals viennent leur disputer la nuit (p. 162). But there are also some sights that truly charm them; perhaps the contrast makes them even more precious. There is a profusion of flowers (des lauriers-cerises; des amandiers; des cactus; des orangers; des grenadiers; des figuiers; des rosiers; des liserons; des loriots; des pinsons; des fauvettes; des mésanges; des glaieuls; des iris; des des fougères; des nénufars; all of them p. 167); there is also a profusion of multicoloured cloths, jewels, precious metals, carpets that make gardens over gardens: On a étalé devant nous de superbes tapis à nuances amorties, aux dessins délicieux; on a retiré de recoins ténébreux des vêtements de soie et de velours brodés d'or, des étoffes tissées d'or et lamées d'argent, des étriers niellés d'or, des armes rares, des sabres à lames damasquinées, et nous sommes partis éblouis de toutes ces richesses datant la plupart d'époques lointaines, que sortaient de leurs trous noirs ces marchands graves, polis, glissant silencieusement comme des ombres, enveloppés de leurs linceuls de mousseline (p. 168). This is what Orient is supposed to be: contrast, profusion, vertigo. G. Montbard, A Travers le Maroc. Notes et Croquis d'un Artiste, une reprise de 1886, Casablanca, Ed. Frontispice, 2013. Leiden, 26.03.2019 |

eating candies in a train compartment

(a humble Muslim from Poland writes back to Hajja Leila Slimani

on the subject of sex and lies)

I do not really know what to think about Sex et mensonges. La vie sexuelle au Maroc. The book makes me remember similar publications that I had to read, many years ago, in connection to Portuguese post-Salazarian feminism. Similar genre of histórias de mulheres: lack of sexual fulfilment, lack of sexual knowledge, lack of contraceptives, social pressure, abortion, servitude, violence. At the same time, the continuity between this book and the publications roughly contemporary of Portuguese feminism, such as L'Amour dans les pays musulmans by Fatéma Mernissi (written and discussed in the 1980s), is bitterly striking. Still more bitter to think how many things come close to the reality of my native Poland. Of course, sex as such is not penalised in Poland. But the laws concerning abortion, the reality of female suicide and many other things are gruesomely similar. In one of the testimonies, I read: Je me sentais coupable avant même d'avoir péché (p. 31). So did I, as young as eleven and twelve. This is why I would say, firstly, that those things do not happen to Moroccan women because they are Muslims. They could be Catholic, to exactly the same avail.

In the end, quite an opposite idea comes to the fore: that Islam fosters the sexual fulfilment rather than inhibits it. I suppose this is a statement that any student of Islamic cultural history will subscribe. And whatever is said about it in Slimani's book is less convincing than the formulation given by Mernissi thirty years ago; or by Chebel, etc. There is no novelty, nor even a pretention of it, this is why Slimani's book has a significant bibliography. Shortly speaking: Il faut trouver une troisième voie et libérer le sexe avec la religion plutôt que contre elle (p. 112). I am under the impression that this is a largely consensual point of view in Islam today. Am I mistaken?

Certainly, Moroccan men are a peculiar kind. The usages of the country are idiosyncratic, even if compared to the rest of Islamic world. It was particularly striking that during my travels in Morocco I used to receive a tremendous number of explicit sexual proposals, on all occasions, even during scientific events at the University Mohammed V in Rabat, etc. To a degree that I started to believe it is a peculiar form of local politeness - sort of compliment to a lady. A gentleman should invite her to bed, but of course everyone knows that it is merely a social ritual and she will refuse politely. More or less like eating candies in a train compartment; it is polite to propose them to the travel companions near you, and to expect that they will refuse.

But also at a closer, and more serious look, Moroccan men are neurotic (the peculiar politeness I've described above is in itself an obvious neurotic symptom; I suppose that most psychiatrists would agree with me that healthy men don't behave in this way). Fatéma Mernissi gave an explanation; she claimed the neurosis is connected to the double oppression they suffered, both in the colonial and post-colonial state. Neurosis of men who had no say in their own country, essentially political and social, but projected on the screen of their relations with women: the last field of action, equally denied to them, the last wall against which they clash. I do believe it might be quite a correct, even if only partial diagnosis. Incidentally, the only Moroccan man I knew close enough to speak about those things with assurance, was born in Nanterre; yet the neurosis connected to his origin was well pronounced, its symptoms fully developed. I would say, in their full blossom. Leila Slimani speaks of Wahhabism; but from my own intimate experience of Saudi Arabia (and of Morocco) I know that Moroccan men internalize the sexual oppression as no Saudi would ever do; they offer a sharp contrast to daring, frankly anarchistic, often shockingly uninhibited Arabian lifestyles. Unless Wahhabism is something that exists in the Maghreb more than it does in its historical homeland, which is also a hypothesis to consider.

Be that as it may, the book of Leila Slimani is filled essentially with conversations of women; men appear episodically and indirectly, mostly the intellectuals, and speaking mostly from their Parisian academic cabinets, while the women are on the terrain, in Casablanca, Agadir, small towns in the south. It is roughly admitted that they are not exactly the beneficiaries of the current situation, not as totally as one might believe. Of course. But the final question to ask is who is thus the main beneficiary of the sexual oppression imposed to Moroccan society. The political power? The religious class? The fundamentalists? Or is it simply a form of collective inertia bringing no true profit to anyone?

This would be my conclusion, the most striking observation that my reading of this book reinforces: Moroccan men are silent, much more silent and silenced than Moroccan women. From my experience, they have an enormous difficulty in communicating anything whatsoever to a woman; this is what makes them - as from my experience - the "difficult men", not their violence, or learned disrespect, or any particular degree of sexual incompetence. Who silenced them? The colonizer? The king? The imam? The da'ui? Or centuries of exclusion from the sphere of authentic intimacy?

And last but not least, ya Hajja, I tried to make love to the men from your country. Come and try to make love to the men from mine! Invite to your bed a true dziaders from Poland! Then you shall know what our great aphorist Stanisław Jerzy Lec meant by this bon mot: Kiedy znalazłem się na dnie, usłyszałem pukanie od spodu ("When I reached the bottom, I heard knocking from beneath"). Then you shall be an impartial judge of everything: disrespect, oppression, sexual incompetence... More than this: sexual life and sexual death. And perhaps you will also find an unexpected universalist and transdenominational depth in the sarcastic sentence of Fatéma Mernissi you quoted in the conclusion of your book: Le bonheur d'une femme viole la qa'ida (p. 182)...

Leila Slimani, Sex et mensonges. La vie sexuelle au Maroc, Paris, Éditions des Arènes, 2017.

Neuville-sur-Oise, Shawwal 27th, 1442.

In the end, quite an opposite idea comes to the fore: that Islam fosters the sexual fulfilment rather than inhibits it. I suppose this is a statement that any student of Islamic cultural history will subscribe. And whatever is said about it in Slimani's book is less convincing than the formulation given by Mernissi thirty years ago; or by Chebel, etc. There is no novelty, nor even a pretention of it, this is why Slimani's book has a significant bibliography. Shortly speaking: Il faut trouver une troisième voie et libérer le sexe avec la religion plutôt que contre elle (p. 112). I am under the impression that this is a largely consensual point of view in Islam today. Am I mistaken?

Certainly, Moroccan men are a peculiar kind. The usages of the country are idiosyncratic, even if compared to the rest of Islamic world. It was particularly striking that during my travels in Morocco I used to receive a tremendous number of explicit sexual proposals, on all occasions, even during scientific events at the University Mohammed V in Rabat, etc. To a degree that I started to believe it is a peculiar form of local politeness - sort of compliment to a lady. A gentleman should invite her to bed, but of course everyone knows that it is merely a social ritual and she will refuse politely. More or less like eating candies in a train compartment; it is polite to propose them to the travel companions near you, and to expect that they will refuse.

But also at a closer, and more serious look, Moroccan men are neurotic (the peculiar politeness I've described above is in itself an obvious neurotic symptom; I suppose that most psychiatrists would agree with me that healthy men don't behave in this way). Fatéma Mernissi gave an explanation; she claimed the neurosis is connected to the double oppression they suffered, both in the colonial and post-colonial state. Neurosis of men who had no say in their own country, essentially political and social, but projected on the screen of their relations with women: the last field of action, equally denied to them, the last wall against which they clash. I do believe it might be quite a correct, even if only partial diagnosis. Incidentally, the only Moroccan man I knew close enough to speak about those things with assurance, was born in Nanterre; yet the neurosis connected to his origin was well pronounced, its symptoms fully developed. I would say, in their full blossom. Leila Slimani speaks of Wahhabism; but from my own intimate experience of Saudi Arabia (and of Morocco) I know that Moroccan men internalize the sexual oppression as no Saudi would ever do; they offer a sharp contrast to daring, frankly anarchistic, often shockingly uninhibited Arabian lifestyles. Unless Wahhabism is something that exists in the Maghreb more than it does in its historical homeland, which is also a hypothesis to consider.

Be that as it may, the book of Leila Slimani is filled essentially with conversations of women; men appear episodically and indirectly, mostly the intellectuals, and speaking mostly from their Parisian academic cabinets, while the women are on the terrain, in Casablanca, Agadir, small towns in the south. It is roughly admitted that they are not exactly the beneficiaries of the current situation, not as totally as one might believe. Of course. But the final question to ask is who is thus the main beneficiary of the sexual oppression imposed to Moroccan society. The political power? The religious class? The fundamentalists? Or is it simply a form of collective inertia bringing no true profit to anyone?

This would be my conclusion, the most striking observation that my reading of this book reinforces: Moroccan men are silent, much more silent and silenced than Moroccan women. From my experience, they have an enormous difficulty in communicating anything whatsoever to a woman; this is what makes them - as from my experience - the "difficult men", not their violence, or learned disrespect, or any particular degree of sexual incompetence. Who silenced them? The colonizer? The king? The imam? The da'ui? Or centuries of exclusion from the sphere of authentic intimacy?

And last but not least, ya Hajja, I tried to make love to the men from your country. Come and try to make love to the men from mine! Invite to your bed a true dziaders from Poland! Then you shall know what our great aphorist Stanisław Jerzy Lec meant by this bon mot: Kiedy znalazłem się na dnie, usłyszałem pukanie od spodu ("When I reached the bottom, I heard knocking from beneath"). Then you shall be an impartial judge of everything: disrespect, oppression, sexual incompetence... More than this: sexual life and sexual death. And perhaps you will also find an unexpected universalist and transdenominational depth in the sarcastic sentence of Fatéma Mernissi you quoted in the conclusion of your book: Le bonheur d'une femme viole la qa'ida (p. 182)...

Leila Slimani, Sex et mensonges. La vie sexuelle au Maroc, Paris, Éditions des Arènes, 2017.

Neuville-sur-Oise, Shawwal 27th, 1442.

contemporary Arabian Ummi-Roman

It happened once when my husband and I were driving carelessly across the Loire Valley. The telephone called. My husband's telephone, I mean, and a female voice spoke, and he answered with such sweetness and tenderness that I felt jealous. Yet I did not comment, for I respect my husband's private life, in the hope that he will respect mine. Till much later.

- It was my mother, of course. What did you expect. The sweetest creature in this world, he said. How should I speak to her, after all what she has done for me?

That is an Arab's ummi, the sweetest creature. Naively inquiring about Loire Valley, and what kind of car did we take from the rental. And if there is enough to eat.

There is also a specific literary genre: novel of my mother. Ummi-Roman, for short. There are many examples all across the Arab world. Hanan Al-Sheikh, The Locust and the Bird. My Mother's Story, of which I spoke briefly in the section dedicated to Lebanon. And in Morocco, the great classic, Driss Chraibi's Civilisation, ma mere!..., of course. And on the other hand, a actualised version, Tahar Ben Jelloun's Sur ma mere. These mothers, invariably, are full of life and drama and colour, and love for their children. And they are illiterate.

Tahar's mother is made of flashbacks. We meet her when she has dementia already. A contemporary topic, apparently so close to the experience of the rich, yet aging European societies. But Tahar throws it back on the Moroccan screen and admits that dementia may not be seen as rich European trouble, but an illness of the poor and the illiterate. If his mother had a richer, more exciting life, she might keep her sanity longer. But her life was empty, lacking intellectual challenge. This is why her old age differed from that of Roland's mother, so satisfied, fulfilled, sparkling till the very moment of her death. Roland's mother had a healthy brain, ready to meet the world. Tahar's mother lived confined, like a prisoner. And faced abuse during years and years on end. This is why her old age is so different, her living conditions are so different, nothing to compare, no point of confluence, even if they tried to make both mothers meet.

Tahar Ben Jelloun, Sur ma mere, Paris, Gallimard, 2008.

Kraków, 31.10.2022.

- It was my mother, of course. What did you expect. The sweetest creature in this world, he said. How should I speak to her, after all what she has done for me?

That is an Arab's ummi, the sweetest creature. Naively inquiring about Loire Valley, and what kind of car did we take from the rental. And if there is enough to eat.

There is also a specific literary genre: novel of my mother. Ummi-Roman, for short. There are many examples all across the Arab world. Hanan Al-Sheikh, The Locust and the Bird. My Mother's Story, of which I spoke briefly in the section dedicated to Lebanon. And in Morocco, the great classic, Driss Chraibi's Civilisation, ma mere!..., of course. And on the other hand, a actualised version, Tahar Ben Jelloun's Sur ma mere. These mothers, invariably, are full of life and drama and colour, and love for their children. And they are illiterate.

Tahar's mother is made of flashbacks. We meet her when she has dementia already. A contemporary topic, apparently so close to the experience of the rich, yet aging European societies. But Tahar throws it back on the Moroccan screen and admits that dementia may not be seen as rich European trouble, but an illness of the poor and the illiterate. If his mother had a richer, more exciting life, she might keep her sanity longer. But her life was empty, lacking intellectual challenge. This is why her old age differed from that of Roland's mother, so satisfied, fulfilled, sparkling till the very moment of her death. Roland's mother had a healthy brain, ready to meet the world. Tahar's mother lived confined, like a prisoner. And faced abuse during years and years on end. This is why her old age is so different, her living conditions are so different, nothing to compare, no point of confluence, even if they tried to make both mothers meet.

Tahar Ben Jelloun, Sur ma mere, Paris, Gallimard, 2008.

Kraków, 31.10.2022.

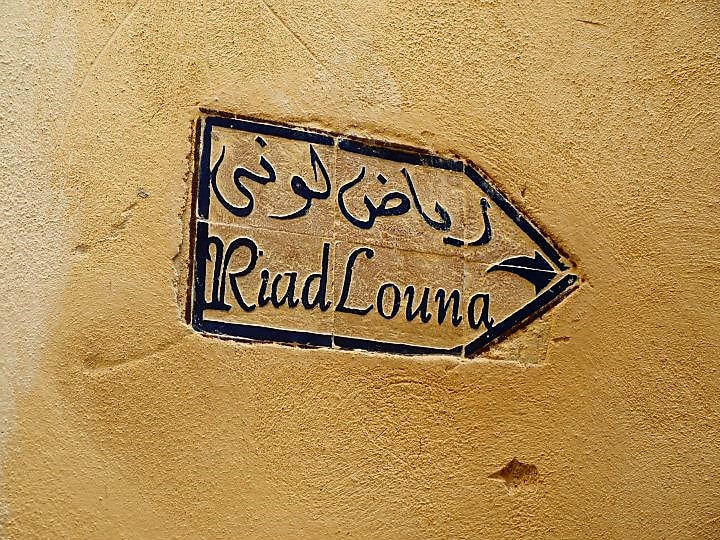

my Moroccan travels and adventures

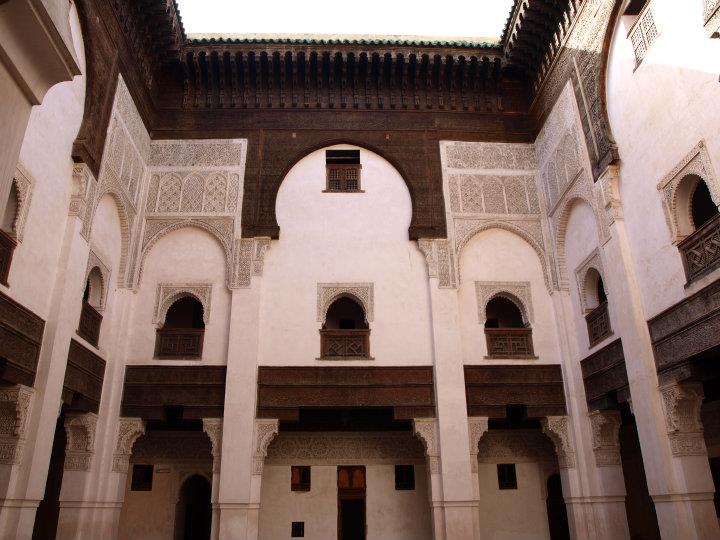

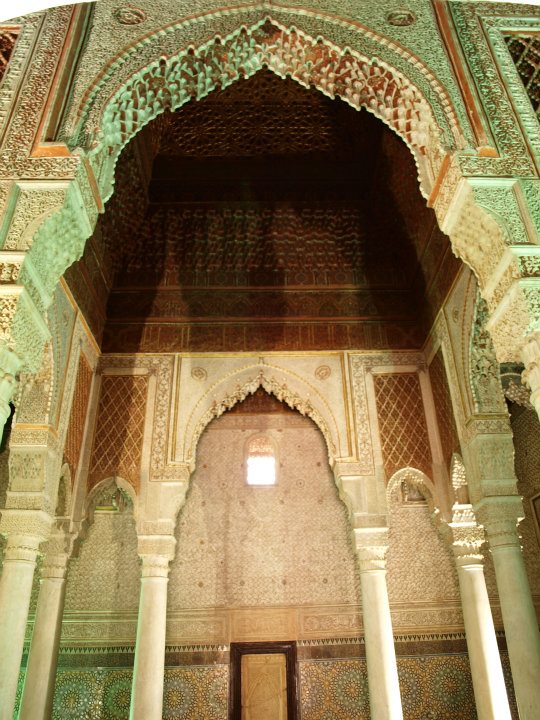

first time in MoroccoMy first travel to Morocco happened in June 2011. This is when I visited Essaouira (Portuguese Mogador) and Al-Jadida with its cistern immortalised in Orson Welles' Otello. I also went for the first time to Casablanca and Rabat, where I was to return in 2013 for a closer encounter. I visited the Roman site of Sala Colonia and the Merinid necropolis, Chellah. I saw the Hassan tower and tried to pray in one the nation's more prestigious mosques, from which I was about to be discreetly removed by a police officer. In Meknes, on the contrary, I was politely invited to Mulai Ismail's mausoleum. Then, on my way to Fes, I saw yet another archaeological site, that of Volubilis, where Roman antiquity meets Berber one. Finally, Fes, and then Marrakesh, were the culminating points of that trip.

|

Volubilis

|

Vertical Divider

|

CasablancaMarch - April 2013.

My travel to Morocco in 2013 had strictly academic porpose. In Casablanca, I was to participate in the Salon International de l'Édition et du Livre (30.03-7.04.2013), and I went there ever day, searching for fresh material for my research, listening to intellectuals, talking to Amazigh activists. I had little time for photography, and these photos have very little of what might be considered as "artistic". Also, I was in no position to display ostentatiously my visual interests; I wouldn't like to be taken for a tourist. I was living on the medinah, being one with it, while I was doing my research on Morocco; some religious people were congratulating me in the quality of a scholar travelling in search of knowledge. This is why I was shy to show my sticky cam, taking pictures of people or even places. Apparently, in Casablanca there is nothing to justify it, no great mosques, no historical sites. There are nicer, more photogenic places. I was living between the port and the royal mosque, and even Habous seemed far, I needed to take a taxi to reach it. Everywhere else, I was going on foot. I was there for the book fair, and to reach it, I was crossing the whole medinah every day, greeting and being greeted by people, sometimes invited to eat with other women. I used to bring fruits or sodas, and a single banana was to be cut in four, to get a part of it for each of us. But for the most of time, I was eating with men, till the day a police commissionaire tried to offer me sadaka, and I decided it was time to pack my stuff and move to Rabat... I keep a cordial record of Casablanca; in no other place across the Muslim world have I ever been as much at home as in this greasy post-colonial city, where a lot of the best of Morocco is concentrated. |

|

Vertical Divider

|

RabatRabat was a completely different story already. Technically speaking, I was still living in the medinah, not far from the Casbah, but completely different quality. It was a nice riyad owned by a French, where the guests were elderly Moroccan Jews, well established on the opposite shore of the Mediterranean, very normal looking, and surprising me by speaking such an Arabic to the service boy. Me too, I was someone else in Rabat, a European, perhaps a European convert. In the Casbah, it happened to me once to meet a freshly converted "sister". She jumped to hug me with exaltation, as if I were her kin or friend or whoever. The Moroccan man accompanying her, red with shame, pledged me to forgiveness. Wasn't the land still bearing the trace of Titus Burckhardt's own feet?...

Strangely, even if Casablanca seems uncontested as the capital of creative Morocco, it is in Rabat that the museums are, and such things. Life is different, or perhaps a mere accident inscribed me differently in space and community. In Rabat, I didn't eat neither with men nor with women. I ate in the restaurant "La Libération", the famous Mat'am al-Hurriyya rendered immortal in Goytisolo's Makbara. Indeed, I couldn't read Makbara otherwise than remembering this city, even if there is also Marrakech, Jemaa al-Fna, perhaps places in superposition, neither here nor there, Rabat, Fès and Marrakech at the same time. In the Mat'am al-Hurriyya everything was woefully cheap, and miserable, and plastic, yet the food was served ritualistically, in the European way, with a strange touch of colonial elegance. For sure nobody would expect to see me eating with my fingers. |