what is Polish literature?

The answer ought to be very clear, as I was educated in Poland and Polish literature was taught to me all along my school years. It was only later on that I started noticing the complication; the frontiers of Polish literature started to blur. Apparently, it is a sum of texts written in Polish. But there is also a Latin part in it, the legacy of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a Yiddish contribution, even texts in French written by Polish Romantics. Polish literature is thus as multilingual as most of the literatures I speak of on this website; also, since its beginnings, it was written not only by Poles, but also by people of other origin, just to give the medieval example of Gallus Anonymous and his Gesta principum Polonorum, narrating the history of Poland since its legendary origins until 1113. Nonetheless, Polish nationalistic vision tends to overlook such facts.

Be that as it may, the beginnings of written literature of Poland are related to Latin chronicles, where the tradition of Gallus was continued by Wincenty Kadłubek, Jan Długosz, Zbigniew Oleśnicki. On the other hand, an early vernacular text is Bogurodzica, a hymn in prise of the Virgin treated as a battle anthem. It was written down in the 15th century, but it must have existed at least a century earlier. Overall, the vernacular literature of Poland dates back from the 14th c., with such manuscripts as Holy Cross Sermons.

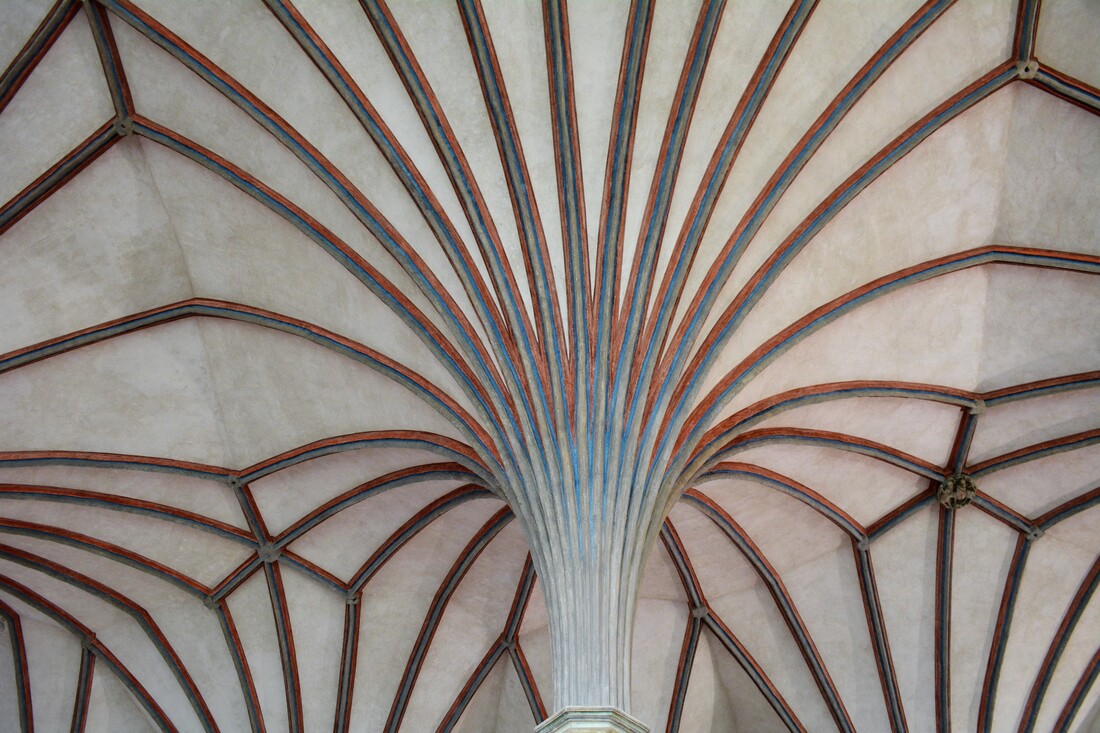

The printing press was introduced early, in the 1470s. A German printer Kasper Staube brought the new technique to Kraków; the printing shop of Wrocław is almost as ancient. Significantly, those early printing centres produced books not only in Latin script, but also in Cyrillic; later on, even print in Arabic was introduced.

The Golden Age of Polish culture is believed to coincide with the Renaissance, and once again it is a period of various foreigners contributing to Polish letters: namely Kallimach (Filippo Buonacorsi) and Conrad Celtis. On the other hand, one of notable international Latin poets was Klemens Janicki (Ianicus). It was also a good time of Kraków Academy, that might have been more cosmopolitan, as I believe, at that time than Jagiellonian University is today.

Also the literature of Polish Baroque is highly reputed. It was still, in a large part, a literature in Latin, with Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski, known all across Europe as Horatius christianus. On the other hand, domestic life was depicted in all its colours in the memoirs of Jan Chryzostom Pasek.

Polish Enlightenment feels already like a period of decadence to me, in spite of various attempts at reforms. Polish-Lithuanian Commonwelth, and Poland as such went into sharp decline that ended with the Third Partition (1795) that washed the country away from the map of Europe. Meanwhile, among the brightest figures were Ignacy Krasicki and Wacław Potocki, an adventurer that left the fabulous Manuscript Found in Saragossa.

Finally, the Romanticism, in spite of the lacking independence and the changing fortunes of national uprisings, is considered the defining heyday of Polish literature, shaping the identity and imagination of the Poles up to the present day. The central figures are the celebrated national "soothsayers" or "bards" (wieszczowie): Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki, as well as a poet obscure in his lifetime that might eventually be my personal favourite, Cyprian Kamil Norwid. Equally influential in the shaping of the Polish mind was the subsequent generation; it was so called Polish Positivism, corresponding roughly to what would be Realism and Naturalism in European letters. It was the time of great novels of Bolesław Prus and Henryk Sienkiewicz, but also of various female writers, such as Maria Konopnicka, Eliza Orzeszkowa, Gabriela Zapolska, and others.

Just like the 19th-c. literature all across Europe, these books make rather painful reading today. But the diverse currents and tendencies, so called Young Poland in 1890-1918 as well as those of the Interbellum period, bring some examples of highly readable literature. Witkacy, even more than Gombrowicz, is my personal favourite, together with a Jew from Drohobycz, Bruno Schulz, a sort of vitalist Kafka from the confines of Europe. Later on, the cataclysm of the ww2, and the subsequent communist period gave a sombre and rather blunt literature, forming a background against which an intellectual refugee, Czesław Miłosz, shines very bright.

Be that as it may, the beginnings of written literature of Poland are related to Latin chronicles, where the tradition of Gallus was continued by Wincenty Kadłubek, Jan Długosz, Zbigniew Oleśnicki. On the other hand, an early vernacular text is Bogurodzica, a hymn in prise of the Virgin treated as a battle anthem. It was written down in the 15th century, but it must have existed at least a century earlier. Overall, the vernacular literature of Poland dates back from the 14th c., with such manuscripts as Holy Cross Sermons.

The printing press was introduced early, in the 1470s. A German printer Kasper Staube brought the new technique to Kraków; the printing shop of Wrocław is almost as ancient. Significantly, those early printing centres produced books not only in Latin script, but also in Cyrillic; later on, even print in Arabic was introduced.

The Golden Age of Polish culture is believed to coincide with the Renaissance, and once again it is a period of various foreigners contributing to Polish letters: namely Kallimach (Filippo Buonacorsi) and Conrad Celtis. On the other hand, one of notable international Latin poets was Klemens Janicki (Ianicus). It was also a good time of Kraków Academy, that might have been more cosmopolitan, as I believe, at that time than Jagiellonian University is today.

Also the literature of Polish Baroque is highly reputed. It was still, in a large part, a literature in Latin, with Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski, known all across Europe as Horatius christianus. On the other hand, domestic life was depicted in all its colours in the memoirs of Jan Chryzostom Pasek.

Polish Enlightenment feels already like a period of decadence to me, in spite of various attempts at reforms. Polish-Lithuanian Commonwelth, and Poland as such went into sharp decline that ended with the Third Partition (1795) that washed the country away from the map of Europe. Meanwhile, among the brightest figures were Ignacy Krasicki and Wacław Potocki, an adventurer that left the fabulous Manuscript Found in Saragossa.

Finally, the Romanticism, in spite of the lacking independence and the changing fortunes of national uprisings, is considered the defining heyday of Polish literature, shaping the identity and imagination of the Poles up to the present day. The central figures are the celebrated national "soothsayers" or "bards" (wieszczowie): Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki, as well as a poet obscure in his lifetime that might eventually be my personal favourite, Cyprian Kamil Norwid. Equally influential in the shaping of the Polish mind was the subsequent generation; it was so called Polish Positivism, corresponding roughly to what would be Realism and Naturalism in European letters. It was the time of great novels of Bolesław Prus and Henryk Sienkiewicz, but also of various female writers, such as Maria Konopnicka, Eliza Orzeszkowa, Gabriela Zapolska, and others.

Just like the 19th-c. literature all across Europe, these books make rather painful reading today. But the diverse currents and tendencies, so called Young Poland in 1890-1918 as well as those of the Interbellum period, bring some examples of highly readable literature. Witkacy, even more than Gombrowicz, is my personal favourite, together with a Jew from Drohobycz, Bruno Schulz, a sort of vitalist Kafka from the confines of Europe. Later on, the cataclysm of the ww2, and the subsequent communist period gave a sombre and rather blunt literature, forming a background against which an intellectual refugee, Czesław Miłosz, shines very bright.

I have readOlga Tokarczuk, Prowadź swój pług przez kości umarłych (2009), Bieguni | Flights (2007)

Dorota Masłowska, Paw królowej (2005), Wojna polsko-ruska pod flagą biało-czerwoną | Snow White and Russian Red (2002), Kochanie, zabiłam nasze koty (2012) Edward Redliński, Konopielka (1973) Czesław Miłosz, Zniewolony umysł (1953) Witold Gombrowicz, Kosmos (1965), Transatlantyk (1953), Ferdydurke (1937) Emil Zegadłowicz, Motory (1938) Bruno Schulz, Sklepy cynamonowe (1933) Witkacy, Nienasycenie | Insatiability (1930) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have writtenWritten exercises. Ancestral magic and emergent intellectuals in Mia Couto, Lhoussain Azergui and Dorota Masłowska

Pisanie na piasku. Niehegemoniczny konstrukt Orientu w Raptularzu Juliusza Słowackiego |

a Polish literature objector

Życie twoje nie sięgnie wyżej niż dach twojego domu; nie polecisz myślą wyżej niż szczyt topoli, która stoi przed twoim oknem; nie podniesiesz się wyżej duchem niż gołąb biały, który na gwizd twój z podniebia na ziarna grochu opada. Zaraz się ograniczysz.

Your life shall not reach higher than the roof of your house; your thought shall not fly higher than the top of the poplar that stands in front of your window; your spirit shall not rise higher than the white pigeon that swoops from the sky, as soon as you whistle, for a handful of beans. You shall immediately impose limitations to yourself.

Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, Podróże do Polski | Travels to Poland

I have always been a very reluctant reader of Polish literature. Of course, I was forced to read it over and over again for school, but I was always avoiding it as far as I could, and favoured any universal reading I could get. This is why my knowledge of Polish literature must be surprisingly shallow. In my youth, I managed to build up some limited appreciation of the Romantics, specially Adam Mickiewicz in his late period. My generalized refusal of Polishness did not allow me to give them justice; today, I would probably rate them much higher than I did in my youth. Among any Polish texts, I could really claim as my own only those who had any kind of universalist claim in them, this is why Czesław Miłosz was my early favourite, with his translations of Kabir and his poem about the grizzly bear that suffered of toothache. I remember the day he got his Noble prize, and no one in Poland knew who he was. In early eighties his books became objects of high value; in any case I had almost no books at all at home, not even those of Polish literature. To a large extend, it remained this way till the present day. Arguably, there are more books in Romanian in my Polyglot Library than proper books of Polish literature. I have a beloved vintage 2-volume edition of Miłosz, bought in the 80ties and read at candlelight in my youth, some mind-boggling books of Witkacy, Nienasycenie and 622 upadki Bunga, an odd volume of Masłowska that I ceased to appreciate in the meantime, and a luxury edition of Słowacki's sketch books from the travel to the Orient that was offered to me by the director of the Ossolineum editorial house. With some accidental volumes of Gombrowicz, Watt and Parnicki, that's more or less all. Oh yes, and I still have those Travels to Poland by Iwaszkiewicz, that I once bought as I searched for inspiration in my own travel writing. But by Jove, it is the ugliest, the most emetic book that exists in the world, awaiting donation to an NGO supporting the cause of literacy and libraries in the countryside. Although I'm not persuaded that having access to such books will greatly increase readership rates among the Poles.

I even thought about making some sort of well-planned acquisition project before I leave Poland, to take those books with me. But how? A suitcase of Polish books to take with me into exile? It's simply not my kind of idea.

elegance & abjection

(songs of proficient mediocrity)

I see very rarely a book to cause abjection. In fact, I can think right now of just one such book. No, it is not Mein Kampf, nor nothing of the kind. It's a volume of memoires, Podróże do Polski, by Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz. A book that had been done with a very clear intention of being pleasant. This is what I hate most. It is for me the bible of Polish mendacity, and what annoys me in particular are the dates that I associate with years of my own life. A very different life, in a very different Poland, quite unlike the one described in the book.

Iwaszkiewicz, a descendant of the former privileged class (he doesn't hesitate to include the photos documenting elegant life before the war, in Ukraine, ladies with elegant little hats and gentlemen's hunting parties), occupies a prominent place in the post-war "cultural elite" (I add the inverted commas quite deliberately). His memories turn obsessively around two types of events: theatre spectacles and burials of great Polish writers, including the macabre tranlatio of Słowacki's remains, to be buried in the national sanctuary in Kraków, together with Mickiewicz. He enjoys the event like a summer excursion, like a pick-nick among the exalted patriotic throngs, and complains about the bad weather that spoiled the fun: Krakowska połowa pogrzebu Słowackiego była mniej udana. W Warszawie była ta cudowna czerwcowa pogoda, która sprawiła, że przejazd statku z trumną pod most Poniatowskiego, pochód z przystani do katedry, wreszcie krótka noc letnia spędzona pod katedrą w olbrzymiej kolejce osób, które chciały dorzucić choć jeden kwiatek do góry kwiecia, która piętrzyła sięprzed trumną, tej samej wysokości co katafalk -- to wszystko zlało się w feeryczną grę, grę świateł, kwiatów, ludzi, w nieprawdopodobne jak gdyby widowisko (p. 85). Fairy game of lights, flowers, people, an improbable quasi-theatrical spectacle -- I translate just the conclusion.

The whole book is dedicated to the making of that simulacrum of Polishness, that illusion of normalcy that was to cover the truth of the impoverished and unhuman country under the communist regime. Everything is described so cutely, with lots of style, underscored by the photos of more and more elegantly dressed ladies. They visit each other, and they go to the theatre, and Iwaszkiewicz even receives the Belgian queen in the Wawel castle. There is a lot of Chopin played in the background. And there is Zakopane, and the Tatra mountains, and Giewont, and excursions, and all that beautiful, elegant life going on and on and on, full of patriotic symbols, full of sacred places, and ladies accompanying poets, and bouquets of field flowers, and villas that somehow survived the war and the communism.

This is precisely the Poland from which I was excluded. There is nothing in this book to let the reader guess that in Poland existed also blocks of miserable flats, in which people like my own grandmother kept hens on the balconies. This book speaks of an alien country. What is more, it epitomises an oppressive regime of imagination that tried to impose its code also upon me. I was excluded from such a reality, but invited to hold such things for sacred, exactly as described. Because those codes of secular, patriotic holiness, resounding Chopin's music, had just one objective: to perpetuate the privilege of the intelligentsia, the former gentry, now disguised as the "cultural elite", that moved from its mansions in Ukraine to Kraków and Warsaw without losing anything. I still had to clash against those people when I came to Kraków and Warsaw myself, in the 1990s. And I lost the fight.

Iwaszkiewicz used to write about different travels, mostly to Italy. He was to give the impression of a man of the world, so admired in a country transformed into a prison, where any travel abroad was far beyond the dreams of the vast majority of people. But the whole thing stinks provincialism so awfully. The elegance under communist regime is so pretentious, of such a doubtful kind. An imitation, a bit of varnish on the surface, just like the style of Iwaszkiewicz's prose, an imitation of something artful, of an intellectual depth: Skrzydlaci obywatele krainy niebios z kranów promiennych rozbyzgują krople turkusowe, aż kontury wieżyc i kominów drgać zaczną prężącą się mocą lazurów. (...) Spojrzenie jedno ku tym szeregom szynszylowych owiec, rozszerzających swe władztwo nad niebem szafirowym aż po szemrzącą na horyzontach puszczę, wystarczy, aby szelest wieczności dobiegł do uszu naszych, zanurzonych w wodę szarzyzny (p. 99, untranslatable; it is supposed to be an artful description of a summer sky). A song of proficient mediocrity.

As I think about it now, perhaps it was better for me to have lost my battle against them, rather than sinking in. For those things, this symbolic formation was still very much alive in my time. It remained to occupy the stage after 1989. The old professors of the Jagiellonian University whom I met in 1997 were still the members of the same prosthetic elite. I did not sink in, because I rejected the Iwaszkiewicz's code even earlier, almost as a child. Of course, I had very few instruments to form my judgement, by perhaps I felt instinctively its falseness.

Thanks God, I did not sink in the swampy ground that Iwaszkiewicz's prose might prepare. I never belonged to his kind of elite. This is why I could have my own travels, and see Europe, rather than Poland, as my home. As I look to it now, I am very glad to have lost.

Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, Podróże do Polski, Poznań, Zysk i S-ka, [s.d.]; originally published in 1978.

Kraków, 9.08.2021.

Iwaszkiewicz, a descendant of the former privileged class (he doesn't hesitate to include the photos documenting elegant life before the war, in Ukraine, ladies with elegant little hats and gentlemen's hunting parties), occupies a prominent place in the post-war "cultural elite" (I add the inverted commas quite deliberately). His memories turn obsessively around two types of events: theatre spectacles and burials of great Polish writers, including the macabre tranlatio of Słowacki's remains, to be buried in the national sanctuary in Kraków, together with Mickiewicz. He enjoys the event like a summer excursion, like a pick-nick among the exalted patriotic throngs, and complains about the bad weather that spoiled the fun: Krakowska połowa pogrzebu Słowackiego była mniej udana. W Warszawie była ta cudowna czerwcowa pogoda, która sprawiła, że przejazd statku z trumną pod most Poniatowskiego, pochód z przystani do katedry, wreszcie krótka noc letnia spędzona pod katedrą w olbrzymiej kolejce osób, które chciały dorzucić choć jeden kwiatek do góry kwiecia, która piętrzyła sięprzed trumną, tej samej wysokości co katafalk -- to wszystko zlało się w feeryczną grę, grę świateł, kwiatów, ludzi, w nieprawdopodobne jak gdyby widowisko (p. 85). Fairy game of lights, flowers, people, an improbable quasi-theatrical spectacle -- I translate just the conclusion.

The whole book is dedicated to the making of that simulacrum of Polishness, that illusion of normalcy that was to cover the truth of the impoverished and unhuman country under the communist regime. Everything is described so cutely, with lots of style, underscored by the photos of more and more elegantly dressed ladies. They visit each other, and they go to the theatre, and Iwaszkiewicz even receives the Belgian queen in the Wawel castle. There is a lot of Chopin played in the background. And there is Zakopane, and the Tatra mountains, and Giewont, and excursions, and all that beautiful, elegant life going on and on and on, full of patriotic symbols, full of sacred places, and ladies accompanying poets, and bouquets of field flowers, and villas that somehow survived the war and the communism.

This is precisely the Poland from which I was excluded. There is nothing in this book to let the reader guess that in Poland existed also blocks of miserable flats, in which people like my own grandmother kept hens on the balconies. This book speaks of an alien country. What is more, it epitomises an oppressive regime of imagination that tried to impose its code also upon me. I was excluded from such a reality, but invited to hold such things for sacred, exactly as described. Because those codes of secular, patriotic holiness, resounding Chopin's music, had just one objective: to perpetuate the privilege of the intelligentsia, the former gentry, now disguised as the "cultural elite", that moved from its mansions in Ukraine to Kraków and Warsaw without losing anything. I still had to clash against those people when I came to Kraków and Warsaw myself, in the 1990s. And I lost the fight.

Iwaszkiewicz used to write about different travels, mostly to Italy. He was to give the impression of a man of the world, so admired in a country transformed into a prison, where any travel abroad was far beyond the dreams of the vast majority of people. But the whole thing stinks provincialism so awfully. The elegance under communist regime is so pretentious, of such a doubtful kind. An imitation, a bit of varnish on the surface, just like the style of Iwaszkiewicz's prose, an imitation of something artful, of an intellectual depth: Skrzydlaci obywatele krainy niebios z kranów promiennych rozbyzgują krople turkusowe, aż kontury wieżyc i kominów drgać zaczną prężącą się mocą lazurów. (...) Spojrzenie jedno ku tym szeregom szynszylowych owiec, rozszerzających swe władztwo nad niebem szafirowym aż po szemrzącą na horyzontach puszczę, wystarczy, aby szelest wieczności dobiegł do uszu naszych, zanurzonych w wodę szarzyzny (p. 99, untranslatable; it is supposed to be an artful description of a summer sky). A song of proficient mediocrity.

As I think about it now, perhaps it was better for me to have lost my battle against them, rather than sinking in. For those things, this symbolic formation was still very much alive in my time. It remained to occupy the stage after 1989. The old professors of the Jagiellonian University whom I met in 1997 were still the members of the same prosthetic elite. I did not sink in, because I rejected the Iwaszkiewicz's code even earlier, almost as a child. Of course, I had very few instruments to form my judgement, by perhaps I felt instinctively its falseness.

Thanks God, I did not sink in the swampy ground that Iwaszkiewicz's prose might prepare. I never belonged to his kind of elite. This is why I could have my own travels, and see Europe, rather than Poland, as my home. As I look to it now, I am very glad to have lost.

Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, Podróże do Polski, Poznań, Zysk i S-ka, [s.d.]; originally published in 1978.

Kraków, 9.08.2021.

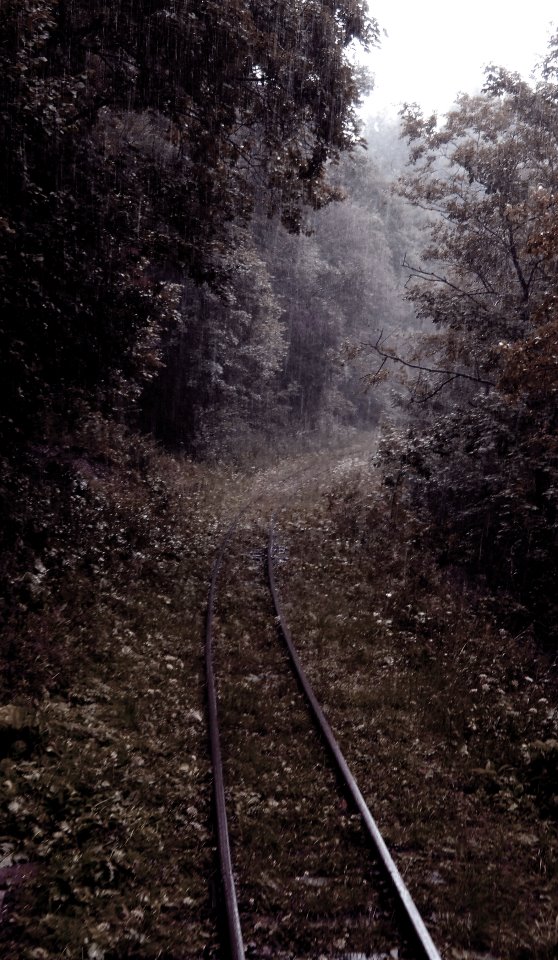

Biebrza National ParkThis swamp region in eastern Poland used to be particularly beloved by husband. The aerial views are taken during a balloon flight.

|

I visited the Biebrza swamps again in June 2015, for a workshop in the framework of the seminar "Between nature and culture" that took place in a research station in Gugny, that I mentioned in The Four Riders as a turning point where I chose an international academic career.

a novel of alphabetization

In a way, it is very surprising why the alphabetisation, its adventure, its drama, its traumas, is so rarely thematised in world literature. And yet it is one of the key processes of modernity! There are just a few examples across Europe, such as Fanga, by Alves Redol, in Portugal. And there is Konopielka, by Edward Redliński, in Poland. What is more, the latter is often read as a story of sexual initiation, rather than alphabetisation, perhaps due to the fact that the literary text, rather unassuming and of modest dimensions, tend to disappear behind the movie realised in 1982 by Witold Leszczyński, precisely at the time when the Poles were discovering eroticism, arguably alien to their cultural tradition.

Be that as it may, I read Konopielka first of all as a novel about the great discovery of writing. It is a story of a teacher sent by the post-war Communist authorities into one of Poland's wildest part, those swamps in the East (the village Taplary in Podlasie region), isolated even from the most modest forms of what would be the peasant culture in other parts of the country. This is why the introduction of scythe instead of sickle* as the main tool of harvesting rye is just as important cognitive revolution as the advent of literacy. And there is the introduction of eroticism, it is true, as the teacher instructs the peasant in the first truly erotic sexual position, the one in which the woman rides the man. A cognitive revolution as well.

There are even more things, such as the introduction of individual beds and plates (sic!), to replace old table manners implying communitarian eating from one family-size bowl. To such a degree that the novel was often criticized in Poland as a sort of grotesque vision of the peasantry's backwardness, completely out of joint with the agronomic revolutions promoted at the time. Even if the narrated time is roughly coinciding with the time when I was born, I knew enough of the shadowy sides of Polish existence to take the writer's narration quite seriously. Only a few years later, I saw with my own eyes those people for whom sleeping in individual beds was still a luxury, and who had no means to wash individual plates after each meal (because the water was drawn manually from the well, and heated on a furnace alimented with wood that also had to be cut manually, and thus divided into smaller logs with a hand axe, a work usually done by women and children). But it is true that they used scythe. The old rusty sickle was just a piece of junk to be found somewhere in the middle of the remaining rubbish, a sign of obsolete cultural reality that was already very distant for them.

But what I really like in this novel, and I find of universal value in global literary studies, is the consciousness flow of the peasant trying to grapple, for the first time, with the signs of writing. All the effort put into bending his cognition based on images, on resemblances, on iconicity to cope with the new grammatological regime.

Edward Redliński, Konopielka, Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza, 1973.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 20.07.2021.

* It is curious to notice that in western Europe scythe replaced sickle before the 16th century; the late medieval figure of Death as the gloomy Reaper is still present in culture to testify of that remote revolution. On the other hand, some say that scythe is much, much older, as old as 5000BC, and that it was precisely an East-European invention; it is referred back to Tripolye culture, somewhere between Moldova and Ukraine. In fact, those peasants in the novel knew the scythe as such, but they had some sort of ritual prohibition related to it: that it offends the rye to use the scythe for harvesting it. By respect, it should be cut with a sickle.

Be that as it may, I read Konopielka first of all as a novel about the great discovery of writing. It is a story of a teacher sent by the post-war Communist authorities into one of Poland's wildest part, those swamps in the East (the village Taplary in Podlasie region), isolated even from the most modest forms of what would be the peasant culture in other parts of the country. This is why the introduction of scythe instead of sickle* as the main tool of harvesting rye is just as important cognitive revolution as the advent of literacy. And there is the introduction of eroticism, it is true, as the teacher instructs the peasant in the first truly erotic sexual position, the one in which the woman rides the man. A cognitive revolution as well.

There are even more things, such as the introduction of individual beds and plates (sic!), to replace old table manners implying communitarian eating from one family-size bowl. To such a degree that the novel was often criticized in Poland as a sort of grotesque vision of the peasantry's backwardness, completely out of joint with the agronomic revolutions promoted at the time. Even if the narrated time is roughly coinciding with the time when I was born, I knew enough of the shadowy sides of Polish existence to take the writer's narration quite seriously. Only a few years later, I saw with my own eyes those people for whom sleeping in individual beds was still a luxury, and who had no means to wash individual plates after each meal (because the water was drawn manually from the well, and heated on a furnace alimented with wood that also had to be cut manually, and thus divided into smaller logs with a hand axe, a work usually done by women and children). But it is true that they used scythe. The old rusty sickle was just a piece of junk to be found somewhere in the middle of the remaining rubbish, a sign of obsolete cultural reality that was already very distant for them.

But what I really like in this novel, and I find of universal value in global literary studies, is the consciousness flow of the peasant trying to grapple, for the first time, with the signs of writing. All the effort put into bending his cognition based on images, on resemblances, on iconicity to cope with the new grammatological regime.

Edward Redliński, Konopielka, Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza, 1973.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 20.07.2021.

* It is curious to notice that in western Europe scythe replaced sickle before the 16th century; the late medieval figure of Death as the gloomy Reaper is still present in culture to testify of that remote revolution. On the other hand, some say that scythe is much, much older, as old as 5000BC, and that it was precisely an East-European invention; it is referred back to Tripolye culture, somewhere between Moldova and Ukraine. In fact, those peasants in the novel knew the scythe as such, but they had some sort of ritual prohibition related to it: that it offends the rye to use the scythe for harvesting it. By respect, it should be cut with a sickle.

the truest book

The truest of all books is Jerzy Kosiński's The Painted Bird. I see in it my own experience like in a mirror. For I also had among my early duties, at the age of eight or nine, to skin the rabbits. They were hit with a blunt tool on their head, and they could be dead or not. The skin had to be removed, and only in the last stage the head could be cut; otherwise, the fur would be stained with blood. Even if it was at a peace time. Even if we had nothing to do with those furs, no use of them. But it was the ancestral ritual that my grandfather cared to transmit to me. And, my hands red with blood till the elbows, I excelled in its performance. My civilised reader might inquire: Why on earth should this macabre task be performed by a child? Perhaps it was an initiation into something that I cannot explain better than Kosiński did.

By curiosity, I check Polish Wikipedia to see how this novel is usually read. I discover that the truest book in my eyes is essentially a false book in the eyes of other people. I find various points of criticism, not the least one stating that Kosiński spent the war hidden in a Catholic family and no one mistreated him. Not particularly. And that for sure he copied this novel somewhere, or it was written by ghost authors. Był znany ze swojego zamiłowania do udawania kogoś, kim nie był. Such things simply cannot be true.

The Wikipedian presentation of the plot is marked by that typically Polish school of misreading that consists basically in omitting the things that the text says with its boldest letters. Kosiński's child hero staje się niemy po tym, jak upadł, próbując wziąć do rąk mszał (loses his speech as he falls, trying to take a missal in his hands). But of course it was not like this. Kosiński's hero loses his speech as a furious Catholic tries to drown him in a latrine tank, where he is conducted by the mob after he has fallen, forced to serve mass as an altar boy, under the weight of an enormous missal book.

And this is also an item in which I mysteriously discover a reflection of my own experience. This was exactly how I lost my original tongue. I mean the part of being plunged into a latrine; I've never served as an altar boy, never tried to touch a missal with my sacrilegious hands.

Jerzy Kosiński, The Painted Bird (1965), read in Polish translation by Tomasz Mirkowicz, in an illustrated edition by Robert Maciej (Baobab, 2003).

Kraków, 28.08.2022.

By curiosity, I check Polish Wikipedia to see how this novel is usually read. I discover that the truest book in my eyes is essentially a false book in the eyes of other people. I find various points of criticism, not the least one stating that Kosiński spent the war hidden in a Catholic family and no one mistreated him. Not particularly. And that for sure he copied this novel somewhere, or it was written by ghost authors. Był znany ze swojego zamiłowania do udawania kogoś, kim nie był. Such things simply cannot be true.

The Wikipedian presentation of the plot is marked by that typically Polish school of misreading that consists basically in omitting the things that the text says with its boldest letters. Kosiński's child hero staje się niemy po tym, jak upadł, próbując wziąć do rąk mszał (loses his speech as he falls, trying to take a missal in his hands). But of course it was not like this. Kosiński's hero loses his speech as a furious Catholic tries to drown him in a latrine tank, where he is conducted by the mob after he has fallen, forced to serve mass as an altar boy, under the weight of an enormous missal book.

And this is also an item in which I mysteriously discover a reflection of my own experience. This was exactly how I lost my original tongue. I mean the part of being plunged into a latrine; I've never served as an altar boy, never tried to touch a missal with my sacrilegious hands.

Jerzy Kosiński, The Painted Bird (1965), read in Polish translation by Tomasz Mirkowicz, in an illustrated edition by Robert Maciej (Baobab, 2003).

Kraków, 28.08.2022.