what is Croatian literature?

The first writer that comes to my mind when I think about Croatia is Dubravka Ugaresic. Yet Croatian literature had its golden age already in the Renaissance age. Nothing is clear, not as clear as we are used to in Western Europe. Croatian language has emerged as a standard, out of a continuum of dialects, only in the 19th century. And then there is still the question of the so called Serbo-Croatian, a language that split into Serbian and Croatian only a few decades ago. It is still essentially the same language (with some regional differences in the vocabulary), but written in Cyrillic for the Serbs and in Latin characters for Croatians. Historically, the literature of Croatia had also been written in Church Slavonic and in Latin.

The question of beginnings is always a tricky one. Of course, like everywhere around the Mediterranean, Croatian cultural and literary tradition emerges from late Antiquity, grows into its empty spaces, just like the medieval town grows into the ruins of the monstrous imperial palace of Diocletian. The oldest samples of writing, such as the so called Splitski evanđelistar (6th-7th century) are to be associated with early Church as the rightful successor of Roman empire. According to a more conservative opinion, Croatian literature starts around the 11th-12th century with Latin hagiography dedicated to Dalmatian and Istrian martyrs such as Saint Duje (the bishop of Salona, the Roman capital of Dalmatia) and Saint Anastasius the Fuller (i.e. an artisan whose occupation was to full cloth). Meanwhile, between late Antiquity and those fully formed Middle Ages with their Latin hagiography, a couple of interesting items emerge from the darkness of the ages: for example stone tablets with Glagolitic inscriptions, such as the Baška tablet discovered in 1851 on the island of Krk. The alphabet that replaced that rather mysterious-looking script was the so called Bosnian Cyrillic. To make things even more complicated, all those scripts sometimes mixed together, making the mediaeval Croatian writing quite unique. Also, the Glagolitic script was in use for a surprisingly long time, to such a degree that in 1483, a Croatian missal became the first book printed in any other letters than the Latin ones.

Dalmatian Renaissance developed under a strong, rather obvious Western influence - that of Italy. The centres of the new culture were both Split and the prosperous merchant Republic of Ragusa, i.e. Dubrovnik; less obviously, also the island of Hvar had its Renaissance heyday. The most widely know Dalmatian humanist was Marco Marulić; his epic poem Judita, written in the Čakavian dialect, was printed in Venice in 1521. The Baroque era was still a literary age for Croatians, in spite of the Turkish menace. In one of the most celebrated texts from that period, Osman, Ivan Gundulić explored precisely the contrast between the freedom of Christian life and the slavery implied by Islam.

The 18th and the 19th centuries brought a new lease of life to Croatian culture. As the northern part of the country found itself under the rule of the Hapsburgs, the new ideas of Enlightenment created a fertile ground for the nationalistic movements of the following century. Romanticism brought about the so called Croatian National Revival, as well as the Illyrian movement (1835), a larger pan-South-Slavic revival in which the Croatians played a leading role.

The question of beginnings is always a tricky one. Of course, like everywhere around the Mediterranean, Croatian cultural and literary tradition emerges from late Antiquity, grows into its empty spaces, just like the medieval town grows into the ruins of the monstrous imperial palace of Diocletian. The oldest samples of writing, such as the so called Splitski evanđelistar (6th-7th century) are to be associated with early Church as the rightful successor of Roman empire. According to a more conservative opinion, Croatian literature starts around the 11th-12th century with Latin hagiography dedicated to Dalmatian and Istrian martyrs such as Saint Duje (the bishop of Salona, the Roman capital of Dalmatia) and Saint Anastasius the Fuller (i.e. an artisan whose occupation was to full cloth). Meanwhile, between late Antiquity and those fully formed Middle Ages with their Latin hagiography, a couple of interesting items emerge from the darkness of the ages: for example stone tablets with Glagolitic inscriptions, such as the Baška tablet discovered in 1851 on the island of Krk. The alphabet that replaced that rather mysterious-looking script was the so called Bosnian Cyrillic. To make things even more complicated, all those scripts sometimes mixed together, making the mediaeval Croatian writing quite unique. Also, the Glagolitic script was in use for a surprisingly long time, to such a degree that in 1483, a Croatian missal became the first book printed in any other letters than the Latin ones.

Dalmatian Renaissance developed under a strong, rather obvious Western influence - that of Italy. The centres of the new culture were both Split and the prosperous merchant Republic of Ragusa, i.e. Dubrovnik; less obviously, also the island of Hvar had its Renaissance heyday. The most widely know Dalmatian humanist was Marco Marulić; his epic poem Judita, written in the Čakavian dialect, was printed in Venice in 1521. The Baroque era was still a literary age for Croatians, in spite of the Turkish menace. In one of the most celebrated texts from that period, Osman, Ivan Gundulić explored precisely the contrast between the freedom of Christian life and the slavery implied by Islam.

The 18th and the 19th centuries brought a new lease of life to Croatian culture. As the northern part of the country found itself under the rule of the Hapsburgs, the new ideas of Enlightenment created a fertile ground for the nationalistic movements of the following century. Romanticism brought about the so called Croatian National Revival, as well as the Illyrian movement (1835), a larger pan-South-Slavic revival in which the Croatians played a leading role.

I have read... nothing ...

|

Vertical Divider

|

I have written... nothing ...

|

my travel to Croatia

early in the season, going down along the Dalmatian coast

April 2017.

Karlobag - Plitvice Lakes - Krka River National Park - Šibenik - Dubrovnik - Split - Trogir

Yet another of those little cheap trips leading south from my Cracovian home. It costs almost nothing, I put up with the lowest of standards, just as a lady with whom I shared the room. But it costs her much more than it does to me. She told me how she managed to save money for it, sweeping floors in churches. I invite her to take a beer in the bar, we seat outside, it is relaxing. I pay discreetly, claiming that the beer is included in the room. Anyway, she has to rely on me, she doesn't speak any foreign language.

I travel the usual road south, to see Plitvicke Lakes and then the Krka River to Šibenik, and then, on a scenic seaside road, down to Dubrovnik, one of the most fashionables cities of the Mediterranean, at least all along these last seasons. As it is so early, its central valley of a street is not crowded yet.

And then Split, with the ancient palace of Diocletian, so big that the whole medieval town enters inside, like corals into an empty shell. And finally Trogir, yet another picturesque town of the Adriatic, where the spring sun tastes so good.

Karlobag - Plitvice Lakes - Krka River National Park - Šibenik - Dubrovnik - Split - Trogir

Yet another of those little cheap trips leading south from my Cracovian home. It costs almost nothing, I put up with the lowest of standards, just as a lady with whom I shared the room. But it costs her much more than it does to me. She told me how she managed to save money for it, sweeping floors in churches. I invite her to take a beer in the bar, we seat outside, it is relaxing. I pay discreetly, claiming that the beer is included in the room. Anyway, she has to rely on me, she doesn't speak any foreign language.

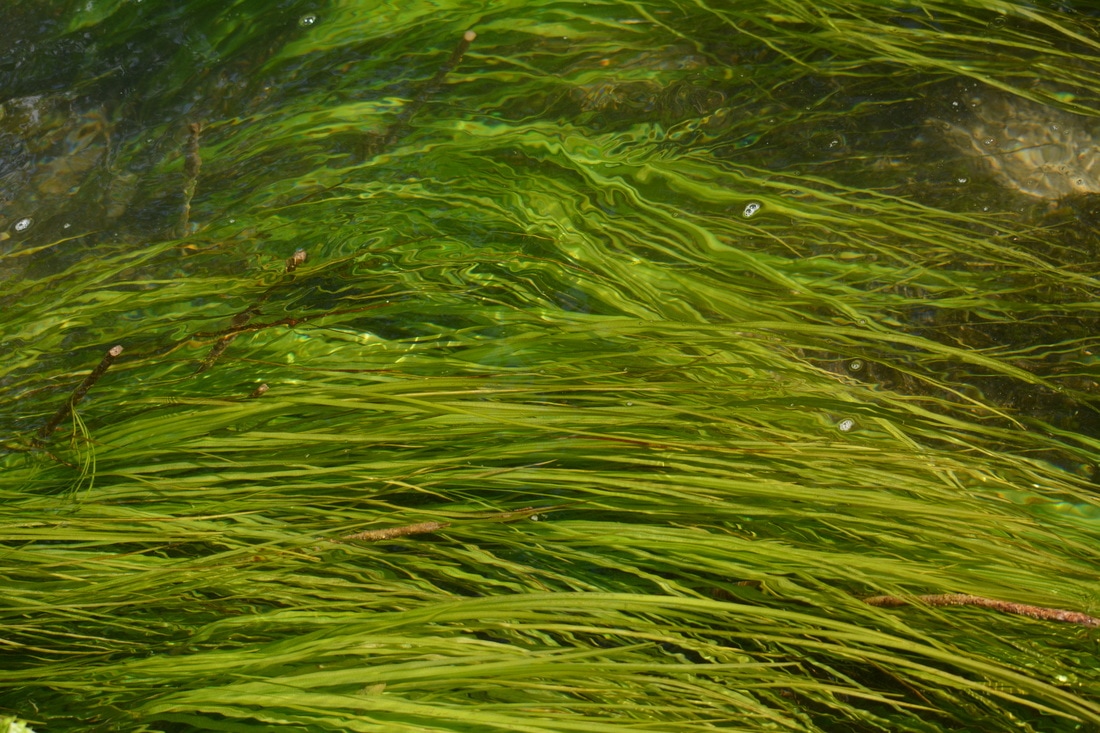

I travel the usual road south, to see Plitvicke Lakes and then the Krka River to Šibenik, and then, on a scenic seaside road, down to Dubrovnik, one of the most fashionables cities of the Mediterranean, at least all along these last seasons. As it is so early, its central valley of a street is not crowded yet.

And then Split, with the ancient palace of Diocletian, so big that the whole medieval town enters inside, like corals into an empty shell. And finally Trogir, yet another picturesque town of the Adriatic, where the spring sun tastes so good.