what is Portuguese literature?

It started in the Middle Ages. Among its oldest examples there are compositions in a language called Galician-Portuguese. Already among those old poems, there are various genres; the most important distinction is that between cantigas do amigo (simple, "popular" ones) and cantigas do amor (refined compositions inspired by Provençal poetry).

The development of Portuguese literature is uninterrupted (contrary to such Iberian literatures as Galician or Catalan, who emerged and flourished in the Middle Ages only to be reborn in the 19th and 20th c.). This is, of course, a phenomenon parallel to almost continuous independence of the Portuguese state (interrupted only for a few decades in 1580-1640).

The 15th and 16th c. brought the maritime expansion of Portugal; this is why the language became present in Brazil and also in various parts of Africa, where Portuguese literature got a varied descendance: not only Brazilian literature, but also various Creole literatures in the islands such as Cape Verde and S. Tome and Principe; finally, there is also a Portuguese-speaking literature in Angola and Mozambique. On the other hand, the Portuguese presence in Asia had less pronounced impact, leaving various books behind, but not consistent literary systems.

Back at home, Portuguese literature followed the usual periodization of West-European cultures: a great Renaissance era culminating in the lyrical and epic work of Camoes, a great, rather peculiar Baroque age with the figure of the Jesuit visionary António Vieira, a rather modest Classicism, and a Romanticism of Garrett and Herculano. It had a great realist-naturalist novel with Eca de Queirós, and then a lot of good poetry, with my favourite Eugenio de Castro and the universally reputed Fernando Pessoa. In the 20th c., the neorealist current is remarkable as the most peculiar expression of the land and its people; its almost direct descendant is Jose Saramago, the only Portuguese Noble prize winner.

The development of Portuguese literature is uninterrupted (contrary to such Iberian literatures as Galician or Catalan, who emerged and flourished in the Middle Ages only to be reborn in the 19th and 20th c.). This is, of course, a phenomenon parallel to almost continuous independence of the Portuguese state (interrupted only for a few decades in 1580-1640).

The 15th and 16th c. brought the maritime expansion of Portugal; this is why the language became present in Brazil and also in various parts of Africa, where Portuguese literature got a varied descendance: not only Brazilian literature, but also various Creole literatures in the islands such as Cape Verde and S. Tome and Principe; finally, there is also a Portuguese-speaking literature in Angola and Mozambique. On the other hand, the Portuguese presence in Asia had less pronounced impact, leaving various books behind, but not consistent literary systems.

Back at home, Portuguese literature followed the usual periodization of West-European cultures: a great Renaissance era culminating in the lyrical and epic work of Camoes, a great, rather peculiar Baroque age with the figure of the Jesuit visionary António Vieira, a rather modest Classicism, and a Romanticism of Garrett and Herculano. It had a great realist-naturalist novel with Eca de Queirós, and then a lot of good poetry, with my favourite Eugenio de Castro and the universally reputed Fernando Pessoa. In the 20th c., the neorealist current is remarkable as the most peculiar expression of the land and its people; its almost direct descendant is Jose Saramago, the only Portuguese Noble prize winner.

I have readWell, almost everything, but in particular:

Afonso Cruz, Paz traz paz (2019), Princípio de Karenina (2018), Flores (2015), Jesus Cristo bebia cerveja (2012) Gonçalo M. Tavares, Uma viagem à Índia (2011) Valter Hugo Mãe, O apocalipse dos trabalhadores (2008) José Luís Peixoto, Nenhum olhar (2000) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have writtenMgławica Pessoa and many other things...

|

my Lisbon: once a capital of the poorest among mankind's many empires

|

I came to Lisbon for the first time in 1993, and I'm unable to tell how many times I returned. I'm a Lusitanist, after all. I've had several grants for research on Portuguese culture: Instituto Camões, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Polish Ministry of Science... This is probably the reason why I have very few particularly good photos from Lisbon. My eye got used to the city too much, or perhaps the city is not as picturesque and photogenic as it is generally believed. In fact, it is, or used to be in my time, a poor, dishevelled place with a peculiar smell, just like old medinas of Morocco. Coming back to Lisbon, I feel like a salmon that recognises the taste of the river of his birth. Olfactory landscapes deserve a research that, as I've heard, is actually being done. I can only try to characterise it in a few words. It is the smell of houses, in the first place, of humidity, since most homes have no heating system whatsoever; mixed with the poignant smell of lye used to sanitise them (I believe that the main effect procured by this massive use of lye on stone and wooden floors is to make it work as an insect repellent). But there are also positive factors in this landscape: eucalyptus, Mediterranean pine trees and other kinds of resinous vegetation.

But the place also have its attraction. The first one, for me, is the quality of food. I love to eat in those little shabby dines far from tourist movement, where a generous jar of excellent Portuguese wine is included in a 6-euro menu. And there is also a specific quality of the human community. Lisbon, especially many of its central parts, such as that between Largo da Graça and Anjos metro station where I used to stay on many of my journeys, is a consummate multicultural place, where people from around the world settle down, bringing with them the warmth of other climates. They laugh a lot, burn candles and incense sticks on tiny altars surrounded with paper flowers, often uniting Buddhas, Hindu divinities and Christian saints on a single little table serving as an improvised altar. They don't take distinctions as seriously as they might; they simply try to survive, with no agenda whatsoever in the city that once used to be the capital of the poorest among mankind's many empires. |

home

I have been a professional reader of the 19th-c. Portuguese literature. And it must be said that I quite enjoyed many books. Yes, that literature was unsophisticated, immature, boorish in more than one place. But there are good things shining bright with an ambivalent light. One of such inspiringly pervert novels is Eça de Queirós' Os Maias, a prescribed reading in Portuguese schools, as I presume. But it appeals, more than anyone might expect, to a very sophisticated reader. There is a charm of home, a nostalgy of home since the very first page, dedicated to the description of "Ramalhete", a noble residence in the picturesque district of Lisbon, Janelas Verdes. At the same time, the home is cursed, not hunted by a ghost like in Victorian stories, but cursed by tragic events that always happen whenever the Maias come to live there. The adjective "tragic" is used in its Greek sense, for it is an involuntary (and later on even a voluntary) incest that comes to the fore. This is why there is a pervasive nostalgy of home, of the beautiful, noble artefacts collected in it, of the big fluffy cat, of the tenderness toward a child, and, on the opposite pole, the urgency of departing, of escape, of going abroad, of non-love.

This is why the novel speaks to me so persuasively, as I have returned to it right now, while liquidating the book collection in my old apartment in Kraków. It brings me recollections of my youth, when I read it for the first time as a student in Lisbon; but it also brings me that persuasive narration of a cursed home. My little flat in Kraków is a Ramalhete of my own with its books and its artefacts, all of them placed under the sign of a tragic destiny that may strike at any moment. Even if, for Eça de Queirós, the cursed moment is love, and desire. For me, it is a cursed History, and the urge of exile.

But there is more, the question of talent that finds no place in a country. Apparently, the naturalist writer criticizes the laziness of his heroes, their inability of finding a sense and a purpose, and working hard; instead of that, they follow, all of them, their male bodily desires and their occasional thirst for revenge on their rivals. They compete for females, and just sometimes happen to ask surprisingly silly questions, such as that if in England there also exists a literature (oh, how many times, by the way, I had to answer to the Poles inquiring if, eg., Arabs also have a literature...). But this relation between talent and country also has a less obvious side. I know it by myself, no matter how hard I try, my country, its ambient mediocrity, sucks the results of my work dry, and there is nothing, a pitiful performance, such as that of the maestro Cruges playing his great composition in the desperate urge of reaching the end.

With all these musings it brings about, the novel is highly readable; it has a rhythm, a suspense. And the sexual topic, after all, is presented in such a way that it has something of an a-temporal, and thus contemporary, relevance in it; it is not just a long gone question of 19th-c. morality. Just like Carlos da Maia, we still get lost in our desires, and in our search for happiness, and the sexual factor overwhelms us. And we are confused about the fine red lines, that still exist, as I suppose. Such as the taboo of incest.

Well, in the end, the big question that Ega has to answer on behalf of his friend is to know if an incest is still such a terrible sin in the 19th century. He decides to tell the truth about the kinship of Carlos and Maria Eduarda, that might otherwise remain unrevealed. The truth that kills the old Afonso da Maia. But it does not kill his grandson Carlos; those generations of modernity are already quite a different, tougher stock. And after all, the tragedy of incest does not have any tragic end whatsoever. Maria Eduarda departs for Paris to live a good life with the money due to her as the newly discovered member of the Maia clan. Carlos and Ega go to Japan and to America and to who knows what other destinations. They return to Lisbon after ten years only to remark that hardly anything matters. And in the famous final scene, they run after that horse-drawn tram.

Eça de Quierós, Os Maias, read from an dishevelled copy that I acquired many years ago.

Kraków, 17.11.2021.

This is why the novel speaks to me so persuasively, as I have returned to it right now, while liquidating the book collection in my old apartment in Kraków. It brings me recollections of my youth, when I read it for the first time as a student in Lisbon; but it also brings me that persuasive narration of a cursed home. My little flat in Kraków is a Ramalhete of my own with its books and its artefacts, all of them placed under the sign of a tragic destiny that may strike at any moment. Even if, for Eça de Queirós, the cursed moment is love, and desire. For me, it is a cursed History, and the urge of exile.

But there is more, the question of talent that finds no place in a country. Apparently, the naturalist writer criticizes the laziness of his heroes, their inability of finding a sense and a purpose, and working hard; instead of that, they follow, all of them, their male bodily desires and their occasional thirst for revenge on their rivals. They compete for females, and just sometimes happen to ask surprisingly silly questions, such as that if in England there also exists a literature (oh, how many times, by the way, I had to answer to the Poles inquiring if, eg., Arabs also have a literature...). But this relation between talent and country also has a less obvious side. I know it by myself, no matter how hard I try, my country, its ambient mediocrity, sucks the results of my work dry, and there is nothing, a pitiful performance, such as that of the maestro Cruges playing his great composition in the desperate urge of reaching the end.

With all these musings it brings about, the novel is highly readable; it has a rhythm, a suspense. And the sexual topic, after all, is presented in such a way that it has something of an a-temporal, and thus contemporary, relevance in it; it is not just a long gone question of 19th-c. morality. Just like Carlos da Maia, we still get lost in our desires, and in our search for happiness, and the sexual factor overwhelms us. And we are confused about the fine red lines, that still exist, as I suppose. Such as the taboo of incest.

Well, in the end, the big question that Ega has to answer on behalf of his friend is to know if an incest is still such a terrible sin in the 19th century. He decides to tell the truth about the kinship of Carlos and Maria Eduarda, that might otherwise remain unrevealed. The truth that kills the old Afonso da Maia. But it does not kill his grandson Carlos; those generations of modernity are already quite a different, tougher stock. And after all, the tragedy of incest does not have any tragic end whatsoever. Maria Eduarda departs for Paris to live a good life with the money due to her as the newly discovered member of the Maia clan. Carlos and Ega go to Japan and to America and to who knows what other destinations. They return to Lisbon after ten years only to remark that hardly anything matters. And in the famous final scene, they run after that horse-drawn tram.

Eça de Quierós, Os Maias, read from an dishevelled copy that I acquired many years ago.

Kraków, 17.11.2021.

the walls of Lisbon

Układ odniesień miasta wyznacza z jednej strony rzeka Tag, a z drugiej wzgórze z Zamkiem św. Jerzego. Widoczne dziś średniowieczne mury siedziby króla Dionizego zostały wzniesione na ruinach twierdzy arabskiej, a ta zaś na pozostałościach murów rzymskich. Na terenie zamku zachowało się kilka okazów bardzo starych drzew oliwnych, pamiętających ponoć czasy panujących tam władców. Ten właśnie zamek, wraz z okalającymi go dzielnicami pojawia się w Historii oblężenia Lizbony. W tle widoczne są wieże centrum handlowego Amoreiras, których Saramago tak nie lubił.

W okolicach zamku położone są najbardziej charakterystyczne dzielnice lizbońskie: Alfama i Mouraria, o chaotycznym układzie wąskich, często ślepych uliczek, gdzie nietrudno się zgubić. To rozplanowanie przypominające labirynt jest właśnie pozostałością miasta wczesnośredniowiecznego, zbudowanego przez Arabów jeszcze przed rekonkwistą i zaistnieniem Portugalii jako państwa. Tuż obok zaskakuje nas jednak bardzo regularny układ ulic. Jest to Baixa Pombalina, nazwana tak od nazwiska męża stanu, Pombala, który tak zręcznie pokierował odbudową miasta po wielkim trzęsieniu ziemi w 1755, że do dziś podziwiać możemy ten porządek urbanistyczny, stanowiący w ówczesnej Lizbonie wielką nowość. Baixa to najbardziej reprezentacyjna część Lizbony, z eleganckimi sklepami i deptakiem. Na pierwszym planie widać plac z pomnikiem króla Jana V; nazywany jest on do dziś Terreiro do Paço, Placem Pałacowym, choć sam pałac królewski został zniszczony w czasie trzęsienia ziemi.

Drugi z centralnych placów położonych na osi miasta zaczynającej się nad brzegiem Tagu przy Terreiro do Paço to Rossio. Właśnie tam mieściła się kiedyś siedziba Inkwizycji, a na samym placu odbywały się auto-da-fé. Dziś jednak nie ma po tym ani śladu, a w miejscu Inkwizycji wzniesiono teatr narodowy. Obszar rozciągający się od tego placu w stronę górujących nad miastem ruin Convento do Carmo to obszar elegancki i zasobny. W kierunku przeciwnym, w stronę Zamku św. Jerzego, dzielnicy Mouraria i alei Almirante Reis zaczyna się Lizbona imigrancka, wielokulturowa, gdzie można trafić na obchody chińskiego Nowego Roku albo festyn organizowany przez jakąś inną społeczność.

Tymczasem oficjalna, lecz mniej barwna oś miasta znajduje przedłużenie w postaci placu Odnowicieli – Restauradores. Nazwa ta jest nawiązaniem do wydarzenia historycznego z roku 1640, gdy zakończyła się unia personalna z Hiszpanią i Portugalia odzyskała pełną niezależność. Tutaj, podobnie jak w Chiado, łatwo natrafić na architekturę modernistyczną, przypadającą na ten sam okres, lecz bardzo różniącą się w wyrazie od naszej secesji.

Lizbona słynie z położenia na pagórkowatym terenie. Dlatego dawniej symbolem miasta były elevadores, różnie rozwiązane pod względem technicznym wyciągi i widny, mające za zadanie ułatwić życie mieszkańcom wyżej położonych dzielnic. Od czasu, gdy Bairro Alto zyskało stację metra, większość dawnych urządzeń popadła w ruinę.

W okolicach zamku położone są najbardziej charakterystyczne dzielnice lizbońskie: Alfama i Mouraria, o chaotycznym układzie wąskich, często ślepych uliczek, gdzie nietrudno się zgubić. To rozplanowanie przypominające labirynt jest właśnie pozostałością miasta wczesnośredniowiecznego, zbudowanego przez Arabów jeszcze przed rekonkwistą i zaistnieniem Portugalii jako państwa. Tuż obok zaskakuje nas jednak bardzo regularny układ ulic. Jest to Baixa Pombalina, nazwana tak od nazwiska męża stanu, Pombala, który tak zręcznie pokierował odbudową miasta po wielkim trzęsieniu ziemi w 1755, że do dziś podziwiać możemy ten porządek urbanistyczny, stanowiący w ówczesnej Lizbonie wielką nowość. Baixa to najbardziej reprezentacyjna część Lizbony, z eleganckimi sklepami i deptakiem. Na pierwszym planie widać plac z pomnikiem króla Jana V; nazywany jest on do dziś Terreiro do Paço, Placem Pałacowym, choć sam pałac królewski został zniszczony w czasie trzęsienia ziemi.

Drugi z centralnych placów położonych na osi miasta zaczynającej się nad brzegiem Tagu przy Terreiro do Paço to Rossio. Właśnie tam mieściła się kiedyś siedziba Inkwizycji, a na samym placu odbywały się auto-da-fé. Dziś jednak nie ma po tym ani śladu, a w miejscu Inkwizycji wzniesiono teatr narodowy. Obszar rozciągający się od tego placu w stronę górujących nad miastem ruin Convento do Carmo to obszar elegancki i zasobny. W kierunku przeciwnym, w stronę Zamku św. Jerzego, dzielnicy Mouraria i alei Almirante Reis zaczyna się Lizbona imigrancka, wielokulturowa, gdzie można trafić na obchody chińskiego Nowego Roku albo festyn organizowany przez jakąś inną społeczność.

Tymczasem oficjalna, lecz mniej barwna oś miasta znajduje przedłużenie w postaci placu Odnowicieli – Restauradores. Nazwa ta jest nawiązaniem do wydarzenia historycznego z roku 1640, gdy zakończyła się unia personalna z Hiszpanią i Portugalia odzyskała pełną niezależność. Tutaj, podobnie jak w Chiado, łatwo natrafić na architekturę modernistyczną, przypadającą na ten sam okres, lecz bardzo różniącą się w wyrazie od naszej secesji.

Lizbona słynie z położenia na pagórkowatym terenie. Dlatego dawniej symbolem miasta były elevadores, różnie rozwiązane pod względem technicznym wyciągi i widny, mające za zadanie ułatwić życie mieszkańcom wyżej położonych dzielnic. Od czasu, gdy Bairro Alto zyskało stację metra, większość dawnych urządzeń popadła w ruinę.

the shades of grey

Portuguese literature, especially when read in extenso, as I used to do by professional duty, tends to be grey. Some contemporary authors learned how to play with this greyness, how to render the richness of greyish hues interesting and "artistic". In the 1960s, in late Salazarian epoch, the greyness was, nonetheless, quite unsophisticated, natural, without any make-up to make her attractive. Such is the literature of the Portuguese middle class, natural and naked, with too little culture to make it brilliant with knowledgeable references, refined language or elegant composition, and on the other hand, without any powerful social cause that might redeem such literary currents as the neorealism. Such are the novels of Fernando Namora, a doctor who decided to turn the musings of his professional practice into books.

I read his 1961 novel, O homem disfarcado, as a part of the project of cleaning my Cracovian apartment, throwing books that are too old and too grey to be taken into the phantasmagorical dream of my exile. So here it is, on its way to the recycle bin, the story of a doctor who suffers from what today we would call a burn-out. To such a degree that, as an accidental witness of an accident, he does not even care to make a few steps to see if a child victim is dead or still alive. I read it in the middle of the pandemic, coinciding, just as I write these words, with the acme of the humanitarian crisis on the Polish border, as well as the furious action of some Polish "patriots" who chop ambulance wheels with machetes and axes just to prevent the doctors from helping the refugees. I think about the burn-out of our doctors here, those few doctors that still remain, while those who could, more intelligent, more talented ones, are already working in places like Oslo and Bergen. Namora's doctor also complains of being a stranger in his own land, in a Portuguese town where he tries to help people, constantly under unfriendly scrutiny, constantly under a vague accusation of who knows what: sexual dissolution at the very least.

No wonder that, after a few years, there is nothing inside, no emotion, no engagement, nothing that might be called a humanistic or humanitarian value of a medic's work. Only a great gaping void that seems so strangely familiar to me. For I know how people hate doctors.

Fernando Namora, O homem disfarcado, 1961.

Kraków, 18.11.2021.

I read his 1961 novel, O homem disfarcado, as a part of the project of cleaning my Cracovian apartment, throwing books that are too old and too grey to be taken into the phantasmagorical dream of my exile. So here it is, on its way to the recycle bin, the story of a doctor who suffers from what today we would call a burn-out. To such a degree that, as an accidental witness of an accident, he does not even care to make a few steps to see if a child victim is dead or still alive. I read it in the middle of the pandemic, coinciding, just as I write these words, with the acme of the humanitarian crisis on the Polish border, as well as the furious action of some Polish "patriots" who chop ambulance wheels with machetes and axes just to prevent the doctors from helping the refugees. I think about the burn-out of our doctors here, those few doctors that still remain, while those who could, more intelligent, more talented ones, are already working in places like Oslo and Bergen. Namora's doctor also complains of being a stranger in his own land, in a Portuguese town where he tries to help people, constantly under unfriendly scrutiny, constantly under a vague accusation of who knows what: sexual dissolution at the very least.

No wonder that, after a few years, there is nothing inside, no emotion, no engagement, nothing that might be called a humanistic or humanitarian value of a medic's work. Only a great gaping void that seems so strangely familiar to me. For I know how people hate doctors.

Fernando Namora, O homem disfarcado, 1961.

Kraków, 18.11.2021.

Sintra

Quinta da Regaleira: the "philosophical mansion"

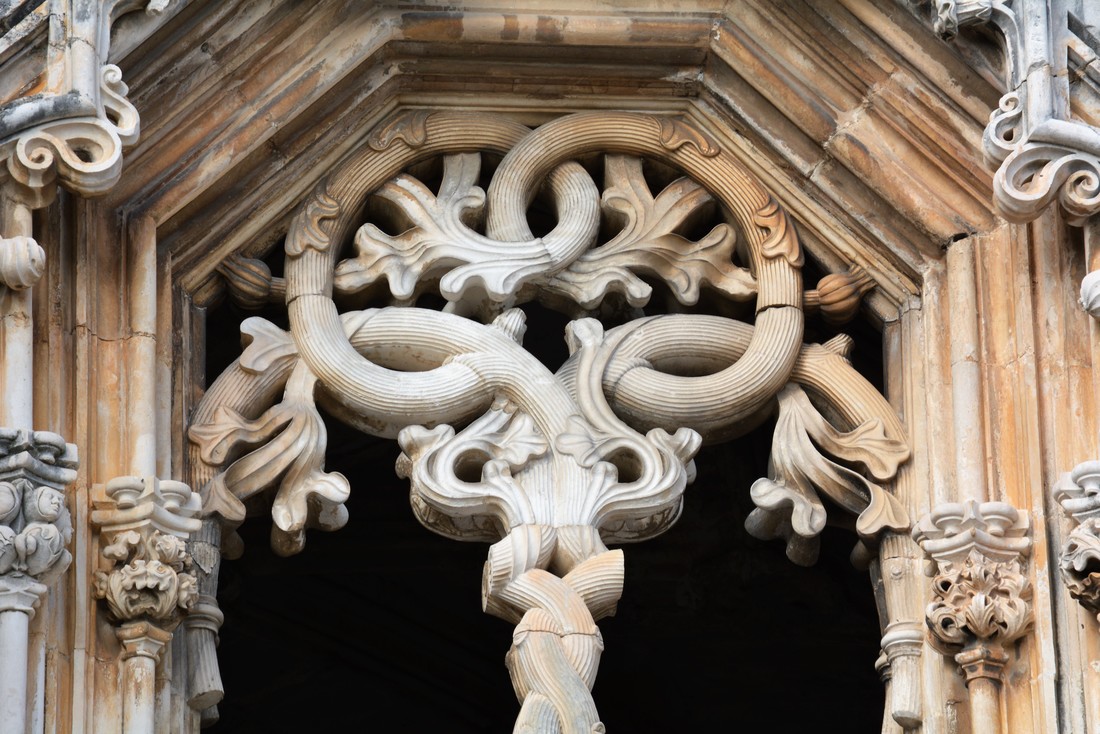

The place called the "garden" (quinta) da Regaleira belonged to a nobilitated merchant family from Porto, the viscounts of Regaleira. In 1892, it was sold to an even richer bourgois owner, Carvalho Monteiro (1848-1920), who decided to build there a neo-Romantic mansion surrounded by a luxurious garden. The result could for some time be seen as the synonym of kitch, yet it is currently recognized as a World Heritage Site. The villa is the work of an Italian architect Luigi Manini, who was - quite symptomatically - a distinguished scenographer and the author of the equally scenic, neo-Manueline Palace Hotel in Buçaco. The villa and the chapel were built between 1904 and 1910-1912 as the result of an eclectic research in neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, and neo-Manueline styles. The vicinity of yet another architectonical fantasy, the Pena palace, justifies the excesses of imagination. On the other hand, as formally diverse as this place might be, it is bound together by the pronounced ideological credo of the owner. Carvalho Monteiro's interest in Free Masonry, alchemy, the Rose+Croix, and the Knights Templar is translated into the visual language of the villa, the park, and a unique hortico-architectural complex intended as a site of Masonic initiation. The richness of the esoteric program makes this architectonical complex something more than a mere neo-Manueline stylization.

Reading the symbolism of the place from the very entrance, the viewer may be fascinated as well as skeptical, because it is evident that much of it serves the ego-aggrandizing purpose of the millionaire. The SALVE at the entrance is a masonic greeting directed toward the visitor, yet the Christian symbolism of the pelican opening its breast to feed the hatchlings with its own blood is a more or less convincing allusion to the owner's philanthropism. In parallel, the pelican is also a Rosicrucian symbol. The profusion of sculpted artichokes that may be found even in the stables refers, on the other hand, to the alchemical process of albedo (the vegerable becomes white under the action of fire). The symbols of initiatic death leading to the rebirth in true, spiritual Light are omnipresent in the mansion, the subterranean part of the chapel, the Grotto de Leda, and the Initiatic Well.

Beja

Ribatejo

Alentejo

Évora

|

The lantern tower of the Catedral of Évora (1280-1340)

One of the most iconic items of the Alentejo region in Portugal, this tower built over the crossing of the main body of the church and its transept is in every tourist's camera. The image is usually taken from the cathedral roof; the opportunity to climb it is an attraction in itself. The Cathedral (Sé) of Évora dates back to the 12th century, and it was considerably enlarged in 1280-1340. It may be seen as one of the best examples of early Gothic architecture in Portugal or in the valley of Douro/Duero river, as the churches in its Portuguese and Spanish parts present considerable similarities. The lantern tower, essentially called like this because its primary function was to provide light to the central part of the church, is also known as the "lantern of the dead" or "torre das cinco quinas". Its spire is surrounded by six turrets, each of them a copy of the tower itself. |

Capela dos Ossos (Chapel of Bones)

love & meat

In the 20th century, Alentejo became arguably the most productive of Portuguese literary destinations. As a great story-producing region, it was invented by the neorealists, who saw unending opportunities of exploiting local forms of social injustice. One of them was Manuel da Fonseca, with his concise novel Seara de vento. It is essentially a story of one family, that of Palma, who lost his job due to his rebel character. There is several of them at home, one of the children is an idiot (crude vocabulary was still admitted at the time the novel was written). They are hungry. There is no money. Yet one day, Palma reinvents himself as a smuggler. This is how he manages to acquire a piece of meat. They finally eat, he and his wife. She eats timidly, he encourages her to eat a little bit more. She is inundated with love and tenderness, and that loyalty of a female who gets fed by the male.

I told the story to my husband, one evening of great happiness, in the Netherlands. He bought a couple of zeebaars for us, and I fried them in abundant butter. Hunger. Tenderness. The loyalty of a female who gets fed. Those things are so far away that speaking of them pierces the boundaries of the accepted discourse. She gets fed by the male, she feels obliged to be loyal to him, for that piece of meat.

Later on, the wife of Palma is manipulated by the police, and inadvertently ends up denouncing his illegal activity. She hangs herself from despair. Palma attacks the landowner who refused to employ him, the primary maker of all their subsequent misfortunes. The idiot boy, hold by his sister, howls.

Yet I still think about the gratitude of the female who got fed, and who loves for a piece of meat. I feel love and tenderness and gratitude for my husband, because he gave me an expensive fish to eat. One December evening in the Hague, it may not be the most politically correct thing to say. But if this detail is silence and forgotten, a great human tragedy of love and tenderness and loyalty is overlooked.

Manuel da Fonseca, Seara de vento, 1958, remembered one December evening in the Netherlands.

The Hague, 7.12.2021.

I told the story to my husband, one evening of great happiness, in the Netherlands. He bought a couple of zeebaars for us, and I fried them in abundant butter. Hunger. Tenderness. The loyalty of a female who gets fed. Those things are so far away that speaking of them pierces the boundaries of the accepted discourse. She gets fed by the male, she feels obliged to be loyal to him, for that piece of meat.

Later on, the wife of Palma is manipulated by the police, and inadvertently ends up denouncing his illegal activity. She hangs herself from despair. Palma attacks the landowner who refused to employ him, the primary maker of all their subsequent misfortunes. The idiot boy, hold by his sister, howls.

Yet I still think about the gratitude of the female who got fed, and who loves for a piece of meat. I feel love and tenderness and gratitude for my husband, because he gave me an expensive fish to eat. One December evening in the Hague, it may not be the most politically correct thing to say. But if this detail is silence and forgotten, a great human tragedy of love and tenderness and loyalty is overlooked.

Manuel da Fonseca, Seara de vento, 1958, remembered one December evening in the Netherlands.

The Hague, 7.12.2021.