what is Greek literature?

Countries with ancient and venerable literary traditions are the hardest to grasp. Greece is evidently one of them. Presumably, it begins around 800 BC with the works attributed to Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey. The classical period, in the 5th century BC, brings about drama, philosophy, historiography. Greek literature lives on across the Roman period and transforms into the Byzantine one, a separate line with its own genres. In the 16th century, the Constantinople is conquered by the Turks, and Greece falls partially out of the Western culture. Only partially, because the 17th century brings about such a phenomenon as the Cretan Renaissance under Venetian rule. Vitsentzos Kornaros (Vincenzo Cornaro, 1553-1613), with his romance Erotokritos, is the most prominent figure of this period.

Modern Greek literature is quite a different story. It starts with the movement Diafotismos, also called the Neo-Hellenic Enlightenment. It developed still inside the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire; nonetheless, the opulence of the Greek merchant class, especially those called Phanariotes (from the Phanar quarter in Istanbul), permitted to finance the studies of its scions in Italy and German-speaking lands. The most important figures of the period are Rigas Feraios and Adamantios Korais.

The Enlightenment created the ideas that fostered the subsequent fight for the independence of Greece from the Ottoman Empire. The political cause gained a vast popularity all across Europe, forming a powerful philhellenic movement. Locally, it was translated into the existence of various secret societies, such as Filiki Eteria (Society of Friends) or Filomousos Eteria. They prepared the ground for the 1821 Greek Revolution.

Greek literature in the 19th century counted with such names as Alexandros Papadiamandis (1851-1911). In the 20th century, Greece had Nobel Prize winners: the poets Giorgos Seferis (1900-1971) and Odysseas Elytis (1911-1996).

Modern Greek literature is quite a different story. It starts with the movement Diafotismos, also called the Neo-Hellenic Enlightenment. It developed still inside the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire; nonetheless, the opulence of the Greek merchant class, especially those called Phanariotes (from the Phanar quarter in Istanbul), permitted to finance the studies of its scions in Italy and German-speaking lands. The most important figures of the period are Rigas Feraios and Adamantios Korais.

The Enlightenment created the ideas that fostered the subsequent fight for the independence of Greece from the Ottoman Empire. The political cause gained a vast popularity all across Europe, forming a powerful philhellenic movement. Locally, it was translated into the existence of various secret societies, such as Filiki Eteria (Society of Friends) or Filomousos Eteria. They prepared the ground for the 1821 Greek Revolution.

Greek literature in the 19th century counted with such names as Alexandros Papadiamandis (1851-1911). In the 20th century, Greece had Nobel Prize winners: the poets Giorgos Seferis (1900-1971) and Odysseas Elytis (1911-1996).

I have readVangelis Raptopulous, Τα τζιτζίκια | The Cicadas (1985)

Aris Alexandrou, Το Κιβώτιο | Mission Box (1975) Nikos Kazantzakis, Βίος και Πολιτεία του Αλέξη Ζορμπά | Zorba the Greek (1946) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have written... nothing ...

|

a travel to Greece, when I was young and handsomeIt was a December, many years ago. Maybe 2007 or 2008. It was one of the first travels we had, my husband and I. We were both young and handsome. I did not know how much I was handsome at the time. I discover it only now, looking back, nostalgically, to that time.

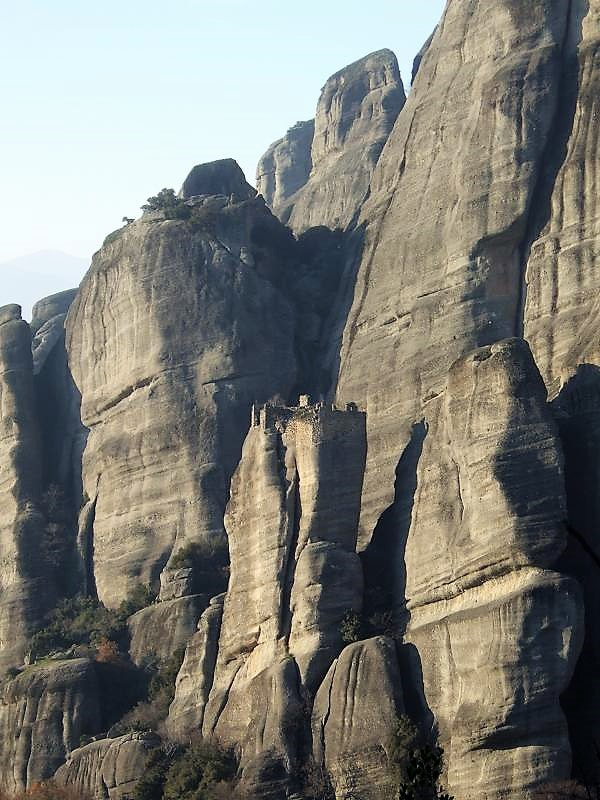

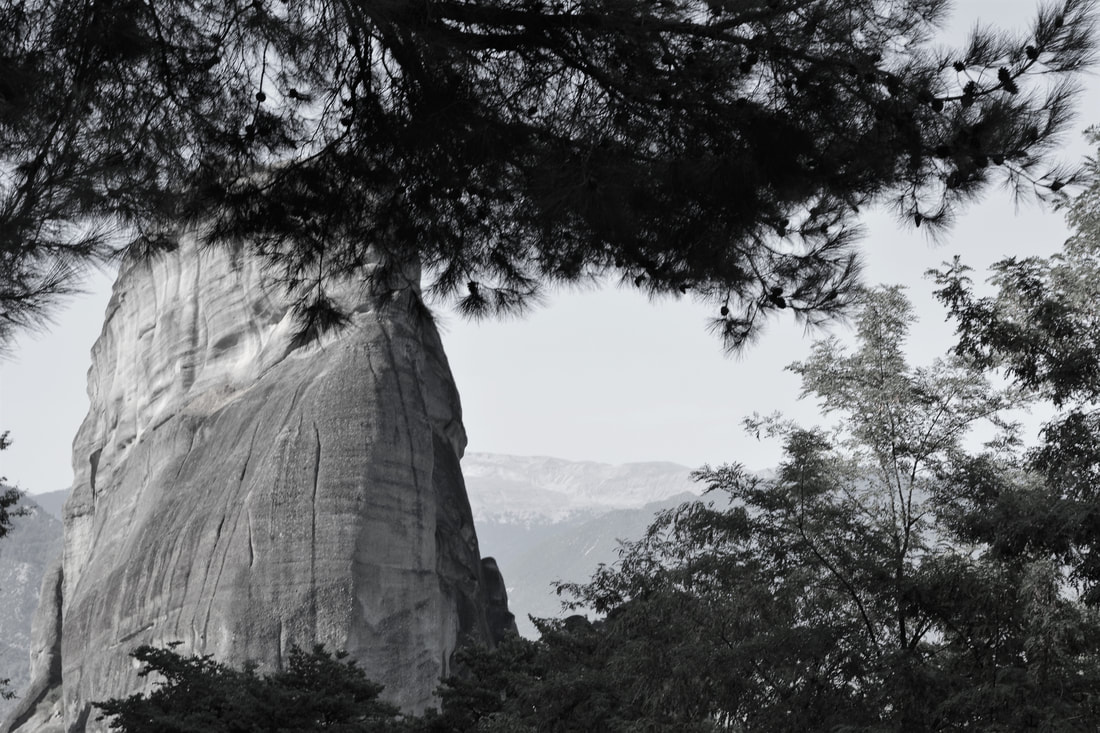

We rented a little red car in Athens and then went down for a ride around the Peloponnesus, till Nafplio, and till Mycenae, and then to Olympia. And then we went a bit north, till Meteora. I was so sorry to have lost most of my photos from this travel in a computer that broke down. It was a time when I did not use to put my photos online yet, not even on Facebook. Probably they were not so very remarkable; I didn't even have a proper camera at the time, just a cheap compact. But they were so special, perhaps because it was such a lonely, melancholic month of December. We were sometimes the only guests in the hotels, and we were in love. Those ruins still stand, and our love as well, but any new travel wouldn't be exactly like that. a travel to Greece, when I'm old and tired of the things I sawAnd here I am again, at the very end of the season of 2021, with the vain expectation of meditating among the ruins. My itinerary covers almost exactly the old trip, with just a couple of additions, such as the Ionian islands. I have shortly been on Corfu in one of my Balkan trips; I add Zakynthos and Kefalonia.

I wish I had a slow travel, like that with my husband, or like those people had in the 19th century, when they kept travel diaries and sketched the views in pencil and aquarelle instead of taking photos. But I'm lazy, and I'm in Greece with a cheap travel agency, surrounded with forty noisy and thoughtless Polish tourists. I have four nights in a hotel on Zakynthos, with a bar and a swimming pool circled by decadent bodies. And just half an hour of time to see Mycenae, before the bus collects all of us for the next attraction, that must appear just as featureless as those stones to my travel companions. No time for meditation on Poland in Agamemnon's tomb, like that of my Romantic predecessor Juliusz Słowacki. And that's better, because I would have to say, just like him, Tak mi smutno (I am so sad). No, I'm not sad; for a finis Poloniae is not the end of Europe. There are still those stones to clench, I can stick to them like an oyster. I quickly confirm the notions received during my high school course in art history: Cyclopean walls, false couple. Archaic period. How archaic, indeed, is hard to fathom. How archaic is the course that cannot be undone. Like the curse that is upon us. |

I muse on how those 19th century travellers managed to cope with the slowness of their journeys, as I try to cope with the instantaneousness of my own. With the contemporary drive for experiencing, for collecting experiences, with this urge of searching for the taste of all things condensed in the fleeting moment, in those 15 minutes that the tour operator reserves for Agamemnon, and for a sea bath, and for a plate of grilled octopus. I take a picture of it with my mobile phone before I even dare to touch it with the point of my knife. Our thirst of pictures, nonetheless, is a direct descendant of that old drive to sketch all views, of that Romantic thirst of the picturesque. We only added technique to desire and achieved the instantaneousness that was already contained in a rapid aquarelle brushstroke.

Alykes on Zakynthos, 2.10.2021.

Alykes on Zakynthos, 2.10.2021.

antiquities

Mycenae | Μυκήνη

Niech fantastycznie lutnia nastrojona, |

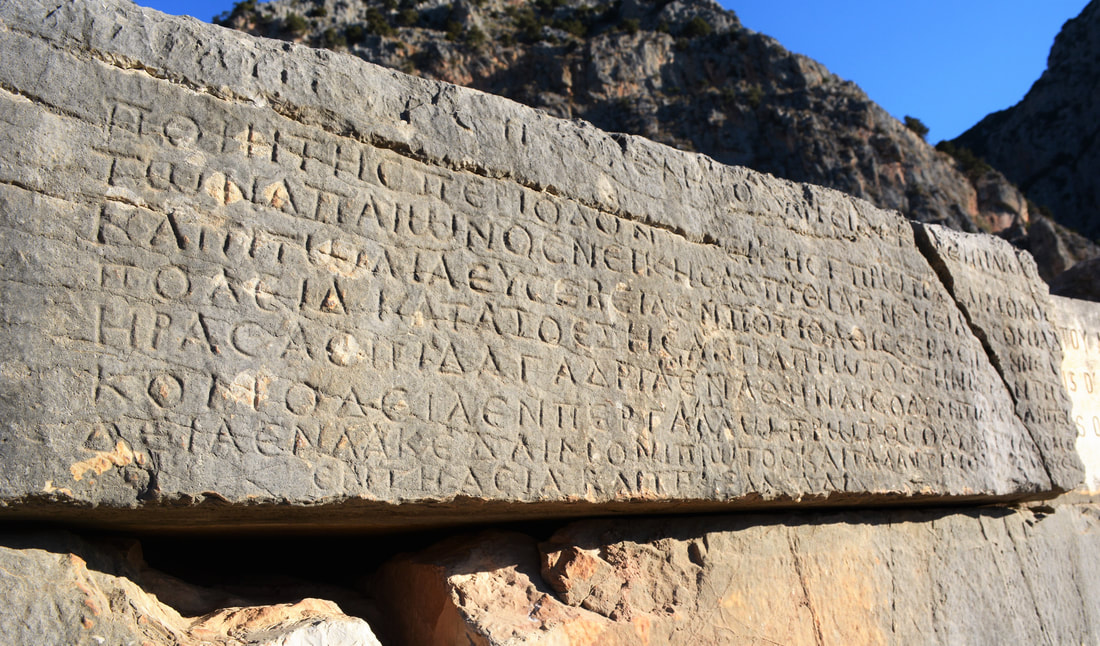

Delphi

Acropolis, Athens

the decline of all things

Acropolis makes a sore impression, hardly inspiring to meditation among ruins. Unless we meditate upon ourselves and the decline of all things that once mattered and that don't actually matter any longer. It is still a symbol, I can see that, it still stands for a source of Europe. Yet not a source of mine, my geography is dislocated; perhaps my source is a Hellenistic Greece, an open, expanding, translating space of in-betweenness, rather than those heavy, static, overwhelming Doric columns.

Be that as it may, the site is overexposed. Bare, arid, dusty, too famous, trodden by too many feet, exposed to the lens too many times in spite of its blatant unpicturesqueness. The Doric style is evidently classical, but it makes upon me the impression of an art not in its heyday, rather of something crude, immature. Many things happened since, and I am more interested in them; I find them missing. In front of the Parthenon, I muse on the juicy, flourishing, abundant decoration of Palmyra, an Eastern, truly female, pregnant form of art, not of that virginal, masculinised femininity that had jumped out of a male head, already in full armour. Certainly, it is all very Western, and speaks of our origins, and our relation to the East, and to the female. And it contains the prophecy of our demise. One day, our remnants will be trodden by too many feet, just like this. And our features will be eaten away like those of the Caryatides.

Athens, 26.09.2021.

Be that as it may, the site is overexposed. Bare, arid, dusty, too famous, trodden by too many feet, exposed to the lens too many times in spite of its blatant unpicturesqueness. The Doric style is evidently classical, but it makes upon me the impression of an art not in its heyday, rather of something crude, immature. Many things happened since, and I am more interested in them; I find them missing. In front of the Parthenon, I muse on the juicy, flourishing, abundant decoration of Palmyra, an Eastern, truly female, pregnant form of art, not of that virginal, masculinised femininity that had jumped out of a male head, already in full armour. Certainly, it is all very Western, and speaks of our origins, and our relation to the East, and to the female. And it contains the prophecy of our demise. One day, our remnants will be trodden by too many feet, just like this. And our features will be eaten away like those of the Caryatides.

Athens, 26.09.2021.

Ionian islands

a ride across Greece

eating

reading

what does Greek literature tell me about European condition

For a long time, the only Greek book in my possession was Zorba, the Greek. I received it as a reward for my excellent performance when I was still at the primary school; I wonder how and why it occurred to my teacher to give me a book so blatantly unfitting my age; probably, she had only the vaguest of ideas about its content. Later on, of course, there were some texts belonging to the ancient Greek literature, a tragedy of Sophocles, a comedy of Aristophanes. But I didn't truly read Kavafis, even. I suppose I should be ashamed of this.

I did. And as soon as I saw a bookshop, I entered and asked for books by Greek authors translated into English. I suppose I wasn't very lucky. There was no Kavafis. The bookshop keeper stretched his hand to one of the lower shelves and brought forth two volumes, rather modestly edited with the support of the Greek Ministry of Culture, a quarter of a century ago (sic!). I bought them both. Apparently, among the crowds of tourists flocking on the Acropolis, the habit of buying Greek novels as a souvenir (rather than bottles of olive oil) has been minoritarian all along this last quarter of a century or so.

And here they are, my two rather accidental Greek books. On the opening pages of a 1975 novel of Aris Alexandrou I can see an imprisoned communist, and the year is 1949. We knew that story in Poland, so to speak the rear end up, since we had Greek communist refugees at the time. The other story is a very different, yet also strangely familiar one. The Cicadas, by Vangelis Raptopoulos, is a book speaking about some sort of lost generation; it immediately made me think of our own Dorota Masłowska. Not entirely exact association, since Raptopoulos is regarded as a distinguished member of the "1980s generation", considerably older than Masłowska; nonetheless, I remember the atmosphere of those years from my childhood, sort of dead end for many people who were young and ready to die at the time, to die an early and inglorious death of a cicada. This is why I feel the story, scrolling down down down the European map, is strikingly familiar. We had them all, the punks and the communists.

Aris Alexandrou, Mission Box, trans. Robert Crist, Athens, Kedros, 1996.

Vangelis Raptopulous, The Cicadas, trans. Fred A. Reed, Athens, Kedros, 1996.

Zakynthos, 4.10.2021 - Kraków, 8.10. 2021.

I did. And as soon as I saw a bookshop, I entered and asked for books by Greek authors translated into English. I suppose I wasn't very lucky. There was no Kavafis. The bookshop keeper stretched his hand to one of the lower shelves and brought forth two volumes, rather modestly edited with the support of the Greek Ministry of Culture, a quarter of a century ago (sic!). I bought them both. Apparently, among the crowds of tourists flocking on the Acropolis, the habit of buying Greek novels as a souvenir (rather than bottles of olive oil) has been minoritarian all along this last quarter of a century or so.

And here they are, my two rather accidental Greek books. On the opening pages of a 1975 novel of Aris Alexandrou I can see an imprisoned communist, and the year is 1949. We knew that story in Poland, so to speak the rear end up, since we had Greek communist refugees at the time. The other story is a very different, yet also strangely familiar one. The Cicadas, by Vangelis Raptopoulos, is a book speaking about some sort of lost generation; it immediately made me think of our own Dorota Masłowska. Not entirely exact association, since Raptopoulos is regarded as a distinguished member of the "1980s generation", considerably older than Masłowska; nonetheless, I remember the atmosphere of those years from my childhood, sort of dead end for many people who were young and ready to die at the time, to die an early and inglorious death of a cicada. This is why I feel the story, scrolling down down down the European map, is strikingly familiar. We had them all, the punks and the communists.

Aris Alexandrou, Mission Box, trans. Robert Crist, Athens, Kedros, 1996.

Vangelis Raptopulous, The Cicadas, trans. Fred A. Reed, Athens, Kedros, 1996.

Zakynthos, 4.10.2021 - Kraków, 8.10. 2021.

Athens again

Church of Theotokos Gorgoepikoos and Ayios Eleutherios | Παναγία Γοργοεπίκοος

There is a lot of debate concerning this little church that I found on my way from Monastiraki to the hotel. It is regarded as a 13th-century construction, yet hard to date with precision, for it is almost entirely built of spolia from various earlier buildings. It is said to have hosted the public library of Athens in the 19th century (presumably, a very small library fitting the post-Independence decades).