what is French literature?

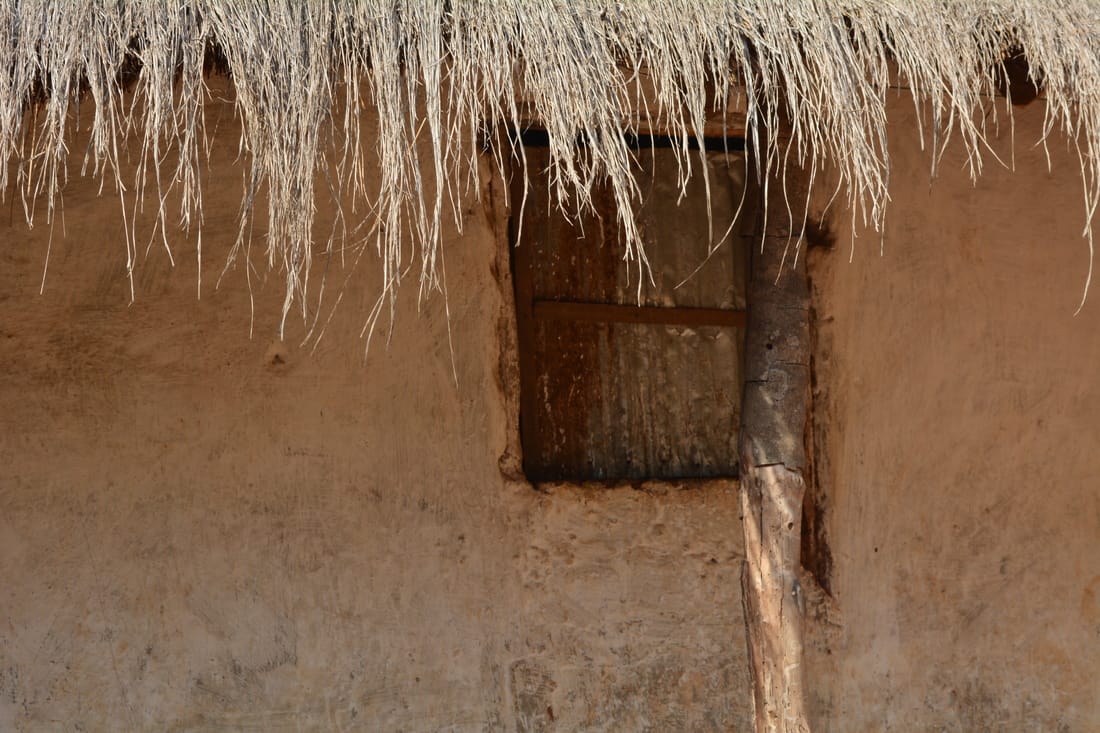

The answer might be simple. Apparently, France is such a centralised state, such a clearly defined hexagon on the map of Europe. But there are complications. I speak of the Occitan literature quite separately, so the French literature here is the descendance of the langue d'oil. An empire in expansion, that conquered the south through a crusade against the Cathars. And later on, there were other expansions, till the emergence of the great colonial empire that even nowadays extends to the Pacific. How French is the literature of New Caledonia?

On the other hand, there is the internal alien, so to speak. What to do with the books written by all those people who came to Paris on their exiles. Is Cioran French?

On the other hand, there is the internal alien, so to speak. What to do with the books written by all those people who came to Paris on their exiles. Is Cioran French?

I have readMichel Houellebecq, Soumission (2015), La carte et le territoire (2010)

Leïla Sebbar, La Seine était rouge. Paris, octobre 1961 (1999) Milan Kundera, La lenteur (1995) Michel Tournier, Vendredi ou les Limbes du Pacifique (1967), Le Roi des Aulnes (1970), Les Météores (1975) Georges Perec, Les Choses (1965) Georges Bataille, La Littérature et le Mal (1957) Marguerite Yourcenar, Mémoires d'Hadrien (1951) Georges Bernanos, Sous le soleil de Satan (1926) Anatole France, L'Ile des pingouins (1908), La Révolte des anges (1914) André Gide, L'immoraliste (1902), Les caves du Vatican (1948) Joris-Karl Huysmans, À rebours (1884) Émile Zola, Germinal (1885), Au Bonheur des Dames (1883), Nana (1880) Gustave Flaubert, La Tentation de saint Antoine (1874), Madame Bovary (1856) Marquis de Sade, Les 120 journées de Sodome (1785) |

Vertical Divider

|

I have writtenAu-delà de la pitié. Guilleragues et Flaubert lus à la lumière de l'essai Naufrage avec spectateur d'Hans Blumenberg

|

peregrinatia ad martyras

I've been very close to France since my studies, in the early 1990s. Not as close as Portugal, but close nonetheless. Yet in spite of various travels, I never had either love or tenderness for this country. Today I live here and they pay me a good money, as no one else does, but the country is still my second choice, a cheaper, clumsier, badly designed ersatz of the Netherlands, an empire and a capital of the world that failed to reinvent itself, a society still living as it was depicted in Madame Bovary, or even worse, on some forgotten page of Bernanos. Un peuple de marmots, he says, in Sous le soleil de Satan. By my idiomatic standards, it is merely an enforced democracy, where a lot of police with interesting guns is to be seen in all sorts of crowded places. It is also an eyesore, with its eternal HLMs on the horizon, when it is not the platitude of the endless fields of sunflowers. Even the greenery has a greyish hue so persuasively captured by Corot. For sure, there is the Midi, the Mediterranean France that I've hardly seen, and the vibrant hues of Van Gogh. But what are we talking about, Van Gogh was Dutch. Overall, this northern part, where I stay most often, is just this: an enforced democracy and an eyesore.

Anyway, in Paris, a great part of one's life goes by underground, and the only landscape to be painted is the olfactive one. For sure, the metropolis has its own characteristic signature, a volcanic stench of hydrogen sulphide, comparable only to Iceland. There is urine, of course, but smelling different than in Lisbon, because it is a sort of rodent secretion, circulating all along the corridors of the underground maze. While the urine of Lisbon drenches stones in the sun.

I've tried hard, but I cannot revive the enthusiasm and the depth of experience of Czesław Miłosz who wrote about Paris in Bypassing Rue Descartes, one of the most important poems that have shaped my intellectual becoming:

I descended toward the Seine, shy, a traveller,

A young barbarian just come to the capital of the world.

[...]

I had left the cloudy provinces behind,

I entered the universal, dazzled and desiring.

Soon enough, many from Jassy and Koloshvar, or Saigon or Marrakesh

Would be killed because they wanted to abolish the customs of their homes.

Soon enough, their peers were seizing power

In order to kill in the name of the universal, beautiful ideas.

Meanwhile the city behaved in accordance with its nature,

Rustling with throaty laughter in the dark,

Baking long breads and pouring wine into clay pitchers,

Buying fish, lemons, and garlic at street markets,

Indifferent as it was to honour and shame and greatness and glory,

Because that had been done already and had transformed itself

Into monuments representing nobody knows whom,

Into arias hardly audible and into turns of speech.

Again I lean on the rough granite of the embankment,

As if I had returned from travels through the underworlds

And suddenly saw in the light the reeling wheel of the seasons

Where empires have fallen and those once living are now dead.

There is no capital of the world, neither here nor anywhere else,

And the abolished customs are restored to their small fame

And now I know that the time of human generations is not like the time of the earth.

[...]

(trans. by Renata Gorczynski and Robert Hass)

Anyway, I cannot ignore that also locally "the universal, beautiful ideas" once tainted the waters of the Seine red, when the "rats", having put their best clothes on, dared to infest, on a autumn Sunday of 1961, the noble quarters of the city. This is why my love and tenderness remains with Jassy and Koloshvar and Marrakesh, and I remain indifferent to honour and shame and greatness and glory of this city. The intellectual, or at least academic, milieu of this country with which I ever had contact is exactly as portrayed on the pages of Houellebecq, except for their erotic life, of which I know nothing. But it appears as a deeply opportunist, passive group, very glad with the privileged positions they managed to occupy in the local system, and entirely out of joint with the great flow of European thought. From time to time they publish something, in their own tongue, and rather without approaching the international journals, as if they needed nothing, had nothing to learn from international exchange. When I still see them so deeply engaged with their own ex-colonial coordinates (the only foreign novels they read, - if any -, seem to be either Algerian or brought from some places deeper in Africa), I think about Lisbon, about how it changed these last twenty years, about the way the Portuguese managed, after all, to get rid of their ex-colonial mentality, to build a different mental map for themselves. The French still live in the margin of the vastness of the empire that was once theirs, still mentally in some sort of Chad, or Cameroon, or Rwanda. And with the sense of their inborn superiority, while they don't even speak correct English.

As I walk down to the Seine through the Boulevard Saint Michel, AD 2021, it crosses my mind that only a young Pashtun taken from home at a tender age might believe, still, that this place is an intellectual capital of a world, any world. There is a three-storey bookshop facing the Cluny museum; I even bought a book in it today, a Tzvetan Todorov's essay on art, written a quarter of a century ago. But a city like Amsterdam has them bigger, with better, fresher books written in a truly universal tongue that French is no more. I just eat my long breads and pour my wine, attentive only to the wheel of the seasons that makes a strident noise as it reels in a mere capital of a fallen empire, where the poets and writers and philosophers who once lived, now are dead. This is probably why of all places here I truly like only Père Lachaise.

Paris, 4.05.2021.

Anyway, in Paris, a great part of one's life goes by underground, and the only landscape to be painted is the olfactive one. For sure, the metropolis has its own characteristic signature, a volcanic stench of hydrogen sulphide, comparable only to Iceland. There is urine, of course, but smelling different than in Lisbon, because it is a sort of rodent secretion, circulating all along the corridors of the underground maze. While the urine of Lisbon drenches stones in the sun.

I've tried hard, but I cannot revive the enthusiasm and the depth of experience of Czesław Miłosz who wrote about Paris in Bypassing Rue Descartes, one of the most important poems that have shaped my intellectual becoming:

I descended toward the Seine, shy, a traveller,

A young barbarian just come to the capital of the world.

[...]

I had left the cloudy provinces behind,

I entered the universal, dazzled and desiring.

Soon enough, many from Jassy and Koloshvar, or Saigon or Marrakesh

Would be killed because they wanted to abolish the customs of their homes.

Soon enough, their peers were seizing power

In order to kill in the name of the universal, beautiful ideas.

Meanwhile the city behaved in accordance with its nature,

Rustling with throaty laughter in the dark,

Baking long breads and pouring wine into clay pitchers,

Buying fish, lemons, and garlic at street markets,

Indifferent as it was to honour and shame and greatness and glory,

Because that had been done already and had transformed itself

Into monuments representing nobody knows whom,

Into arias hardly audible and into turns of speech.

Again I lean on the rough granite of the embankment,

As if I had returned from travels through the underworlds

And suddenly saw in the light the reeling wheel of the seasons

Where empires have fallen and those once living are now dead.

There is no capital of the world, neither here nor anywhere else,

And the abolished customs are restored to their small fame

And now I know that the time of human generations is not like the time of the earth.

[...]

(trans. by Renata Gorczynski and Robert Hass)

Anyway, I cannot ignore that also locally "the universal, beautiful ideas" once tainted the waters of the Seine red, when the "rats", having put their best clothes on, dared to infest, on a autumn Sunday of 1961, the noble quarters of the city. This is why my love and tenderness remains with Jassy and Koloshvar and Marrakesh, and I remain indifferent to honour and shame and greatness and glory of this city. The intellectual, or at least academic, milieu of this country with which I ever had contact is exactly as portrayed on the pages of Houellebecq, except for their erotic life, of which I know nothing. But it appears as a deeply opportunist, passive group, very glad with the privileged positions they managed to occupy in the local system, and entirely out of joint with the great flow of European thought. From time to time they publish something, in their own tongue, and rather without approaching the international journals, as if they needed nothing, had nothing to learn from international exchange. When I still see them so deeply engaged with their own ex-colonial coordinates (the only foreign novels they read, - if any -, seem to be either Algerian or brought from some places deeper in Africa), I think about Lisbon, about how it changed these last twenty years, about the way the Portuguese managed, after all, to get rid of their ex-colonial mentality, to build a different mental map for themselves. The French still live in the margin of the vastness of the empire that was once theirs, still mentally in some sort of Chad, or Cameroon, or Rwanda. And with the sense of their inborn superiority, while they don't even speak correct English.

As I walk down to the Seine through the Boulevard Saint Michel, AD 2021, it crosses my mind that only a young Pashtun taken from home at a tender age might believe, still, that this place is an intellectual capital of a world, any world. There is a three-storey bookshop facing the Cluny museum; I even bought a book in it today, a Tzvetan Todorov's essay on art, written a quarter of a century ago. But a city like Amsterdam has them bigger, with better, fresher books written in a truly universal tongue that French is no more. I just eat my long breads and pour my wine, attentive only to the wheel of the seasons that makes a strident noise as it reels in a mere capital of a fallen empire, where the poets and writers and philosophers who once lived, now are dead. This is probably why of all places here I truly like only Père Lachaise.

Paris, 4.05.2021.

the tale of two Europes

On the shelf with used books, here called proudly a Bibliothèque Participative, I found an old edition of Milan Kundera's La Lenteur, the first, or one of the first books written by the Czech writer directly in French, published in 1995. It was before the access of the East to the European Union. Czech Republic joined it, just like Poland, on May 1st, 2004, some nine years after Kundera wrote his book, and exactly 17 years before I write these words. How much of it remains valid? Well, for sure the active ignorance of the French; no use to tell them any curiosity facts about Eastern Europe; first of all they don't want to admit that they miss anything whatsoever. The competence of an East European is considered unpolite; it should never confront the ignorance of a French. The East European should not meddle in western affaires, if he is not to lose his last remaining tooth, just as it happened to the poor Czech entomologist.

The novel has several layers, the erotic one, and the one relating memory and slowness, as indicated in the title. Yet it is the story of the entomologist removed from the university in 1968, and participating in his first international conference after an absence of twenty years in the academic world, that keeps me more attentive, engages me emotionally. Twenty years is the span of academic career that I lost in Poland; I have been removed from universities, but never in such a way as to seek a job on a building site, as the Czech was forced to do. Also my relation with European academic context is certainly not such as that of the melancholically proud entomologist. But still there is no equality. Of course, not all Europe is as aggressive, and also not as shallow and stupid as France. Kundera's depiction of the Grande Bêtise is grotesque and at the same time strangely persuasive. Nonetheless, there are better universities and less silly people in Germany or in the Netherlands. But it happened just yesterday that I talked to my Dutch vriendjes in a chat room, after an online lecture. They asked me what I will do after Paris, and I said I don't know, perhaps I go to Romania. The feeble uuu that followed was sincerely compassionate, but nonetheless symptomatic. A quarter of the century after Kundera's book, and seventeen years after political integration, there are still two Europes, that may meet more often and more pacifically at international conferences, but many a sore tooth is still the sole basis for a shaky prosthesis of some kind.

And yes, there is slowness that Europe direly lacks. I am a slow lover and also a slow scholar. And yes, perhaps I am the first European at home in the West, and at the same time in full awareness of the difference between Prague, Warsaw, Budapest and even Cluj-Napoca, in the heart of Transylvania. And I must be tough, just as the Czech entomologist portraited with his well-developed musculature in Kundera's story. Massive and blinded like a German tank in confrontation with the Grande Bêtise of the French. Or this is what I would just like to be, gathering my wits across the great arch, buckling Europe in a single flight from Lisbon to Kiev. Because there is no more time to procrastinate, now, when the History is rape to close its great circle, and the things may collapse again at any moment.

Milan Kundera, La Lenteur, Paris, Gallimard, 1995.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 1.05.2021.

The novel has several layers, the erotic one, and the one relating memory and slowness, as indicated in the title. Yet it is the story of the entomologist removed from the university in 1968, and participating in his first international conference after an absence of twenty years in the academic world, that keeps me more attentive, engages me emotionally. Twenty years is the span of academic career that I lost in Poland; I have been removed from universities, but never in such a way as to seek a job on a building site, as the Czech was forced to do. Also my relation with European academic context is certainly not such as that of the melancholically proud entomologist. But still there is no equality. Of course, not all Europe is as aggressive, and also not as shallow and stupid as France. Kundera's depiction of the Grande Bêtise is grotesque and at the same time strangely persuasive. Nonetheless, there are better universities and less silly people in Germany or in the Netherlands. But it happened just yesterday that I talked to my Dutch vriendjes in a chat room, after an online lecture. They asked me what I will do after Paris, and I said I don't know, perhaps I go to Romania. The feeble uuu that followed was sincerely compassionate, but nonetheless symptomatic. A quarter of the century after Kundera's book, and seventeen years after political integration, there are still two Europes, that may meet more often and more pacifically at international conferences, but many a sore tooth is still the sole basis for a shaky prosthesis of some kind.

And yes, there is slowness that Europe direly lacks. I am a slow lover and also a slow scholar. And yes, perhaps I am the first European at home in the West, and at the same time in full awareness of the difference between Prague, Warsaw, Budapest and even Cluj-Napoca, in the heart of Transylvania. And I must be tough, just as the Czech entomologist portraited with his well-developed musculature in Kundera's story. Massive and blinded like a German tank in confrontation with the Grande Bêtise of the French. Or this is what I would just like to be, gathering my wits across the great arch, buckling Europe in a single flight from Lisbon to Kiev. Because there is no more time to procrastinate, now, when the History is rape to close its great circle, and the things may collapse again at any moment.

Milan Kundera, La Lenteur, Paris, Gallimard, 1995.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 1.05.2021.

an athan over Paris

It is almost a half of my stay here. Finally, I'm reading Houellebecq's Soumission, although I had promised myself to read it first thing after my arrival here. Unsurprisingly, I identify with several ideas, such as that of triplication of the professors' salaries and La Sorbonne sponsored by the Saudis (meanwhile, Saudi Arabia, as a source of unconditional founding, has almost disappeared under the horizon; Houellebecq couldn't have predicted that). And of course the idea of Mediterranean Europe, not necessarily as a restitutio imperii, but at least as a restitutio oecumenae. I am very much in favour of this. Instead of aimless sponsoring of those territories eastwards where the only dream, deep down, is the restitutio of Moscow as the Third Rome.

I can't avoid subscribing to the pervasive sadness of this novel. I am a decadent myself, and I used to love Huysmans just as the novel's hero did, although I only wrote a single conference paper about À rebours, and the text was lost due to a computer failure. I see his point, a very pertinent point indeed, the death of Christianity. The inefficiency of Madonna de Rocamadour and of those abbeys in the vicinity of Poitiers. I am sensitive to the charm of Christian tradition, how could be otherwise, but also to the stale smell of all those Benedictine abbeys, the rampant depressiveness of Hildegard von Bingen. And curiously, my Christianity has nothing Polish in it. It is a Romance Christianity, entirely western. As a part of my Polish destiny, I rejected it long ago, in my early teens. So it survived exclusively as a westernised, museal Christianity of a late, very late European erudite. A Petronius of Christian Europe.

There are resemblances, I see myself in this novel, to such a degree that it pains me. Houellebecq's hero was removed from Sorbonne about the same age as I, when the vogue of Christian -rather than Islamic- fundamentalism washed me out of the University of Warsaw. I try to live -and live intensely- the remaining twenty years of intellectual career that I have in front of me. But the temptation of giving up, lived by the hero, is also very much mine. The supreme temptation of passivity.

Last but not least, I am sensitive to the poignant eroticism of this novel, to the fate of being abandoned that European modernity has brought to our erotic destinies. Arabian love never ends; this is why it ends up in death, precisely because it does not have any natural ending, it doesn't burn out. European love does end; according to the author's diagnosis, it lasts one academic year. And the way is down down down, with the natural decadence of human body, female and male as well. Lover of his students, the hero ends up paying for sex, finally overcome by his own anhedonia.

Yet there is an even more pungent moment in Soumission, the death of the hero's mother, that putain névrosée, an abandoned woman who ends up buried in a communal grave because no one reacted even to the news of her death. The quintessential portrait of the female old age in Europe. Certainly not as sympa as that of her ex-husband. He could at least buy, and fill his remaining time with trinkets such as his hunting accessories, while she could not.

In the background, an Islamic call for prayer -never directly mentioned, as I think, in the text- rising over Paris. It would awake me from the deepest depression, tenfold more efficient than Faust's bells of Easter. In fact, it did awake me on several dire occasions. Strangely, looking down from Monmartre, it is so easy for me to imagine Paris as Istanbul or Cairo or Casablanca, at sunset, when suddenly the call for prayer starts in one mosque, and immediately a hundred voices take it up across the city.

But there is one thing that should be stressed. This novel's title is not referring to Islam, it is not a translation of an Arabic word. It is all about the submission of the French, more specifically French intellectual elite. Its epicentre, almost at the end of the book, is the pavilion where the erotic Story of O. once took place, now occupied by the new university rector. Muslim conquerors look like Tunisian shopkeepers, and this is what they are, till the very end. The choice that the hero faces on the last pages of this novel is not to convert or die. It is an even more pressing exhortation: convert and fuck. This is why I have no doubt that he will. Because it is his sole chance to recover his access to young females, those second-year students he used to enjoy all along his academic existence. The great promise of Islam is that they will be still very proud to marry, coming in fours, the aging scholar. Available, like in the old Histoire d'O, for oral, vaginal, and anal penetration. For it is the woman, at the end of the day, who pays for everything.

Michel Houellebecq, Soumission, Paris, Flammarion, 2015.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 24.02.2021.

I can't avoid subscribing to the pervasive sadness of this novel. I am a decadent myself, and I used to love Huysmans just as the novel's hero did, although I only wrote a single conference paper about À rebours, and the text was lost due to a computer failure. I see his point, a very pertinent point indeed, the death of Christianity. The inefficiency of Madonna de Rocamadour and of those abbeys in the vicinity of Poitiers. I am sensitive to the charm of Christian tradition, how could be otherwise, but also to the stale smell of all those Benedictine abbeys, the rampant depressiveness of Hildegard von Bingen. And curiously, my Christianity has nothing Polish in it. It is a Romance Christianity, entirely western. As a part of my Polish destiny, I rejected it long ago, in my early teens. So it survived exclusively as a westernised, museal Christianity of a late, very late European erudite. A Petronius of Christian Europe.

There are resemblances, I see myself in this novel, to such a degree that it pains me. Houellebecq's hero was removed from Sorbonne about the same age as I, when the vogue of Christian -rather than Islamic- fundamentalism washed me out of the University of Warsaw. I try to live -and live intensely- the remaining twenty years of intellectual career that I have in front of me. But the temptation of giving up, lived by the hero, is also very much mine. The supreme temptation of passivity.

Last but not least, I am sensitive to the poignant eroticism of this novel, to the fate of being abandoned that European modernity has brought to our erotic destinies. Arabian love never ends; this is why it ends up in death, precisely because it does not have any natural ending, it doesn't burn out. European love does end; according to the author's diagnosis, it lasts one academic year. And the way is down down down, with the natural decadence of human body, female and male as well. Lover of his students, the hero ends up paying for sex, finally overcome by his own anhedonia.

Yet there is an even more pungent moment in Soumission, the death of the hero's mother, that putain névrosée, an abandoned woman who ends up buried in a communal grave because no one reacted even to the news of her death. The quintessential portrait of the female old age in Europe. Certainly not as sympa as that of her ex-husband. He could at least buy, and fill his remaining time with trinkets such as his hunting accessories, while she could not.

In the background, an Islamic call for prayer -never directly mentioned, as I think, in the text- rising over Paris. It would awake me from the deepest depression, tenfold more efficient than Faust's bells of Easter. In fact, it did awake me on several dire occasions. Strangely, looking down from Monmartre, it is so easy for me to imagine Paris as Istanbul or Cairo or Casablanca, at sunset, when suddenly the call for prayer starts in one mosque, and immediately a hundred voices take it up across the city.

But there is one thing that should be stressed. This novel's title is not referring to Islam, it is not a translation of an Arabic word. It is all about the submission of the French, more specifically French intellectual elite. Its epicentre, almost at the end of the book, is the pavilion where the erotic Story of O. once took place, now occupied by the new university rector. Muslim conquerors look like Tunisian shopkeepers, and this is what they are, till the very end. The choice that the hero faces on the last pages of this novel is not to convert or die. It is an even more pressing exhortation: convert and fuck. This is why I have no doubt that he will. Because it is his sole chance to recover his access to young females, those second-year students he used to enjoy all along his academic existence. The great promise of Islam is that they will be still very proud to marry, coming in fours, the aging scholar. Available, like in the old Histoire d'O, for oral, vaginal, and anal penetration. For it is the woman, at the end of the day, who pays for everything.

Michel Houellebecq, Soumission, Paris, Flammarion, 2015.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 24.02.2021.

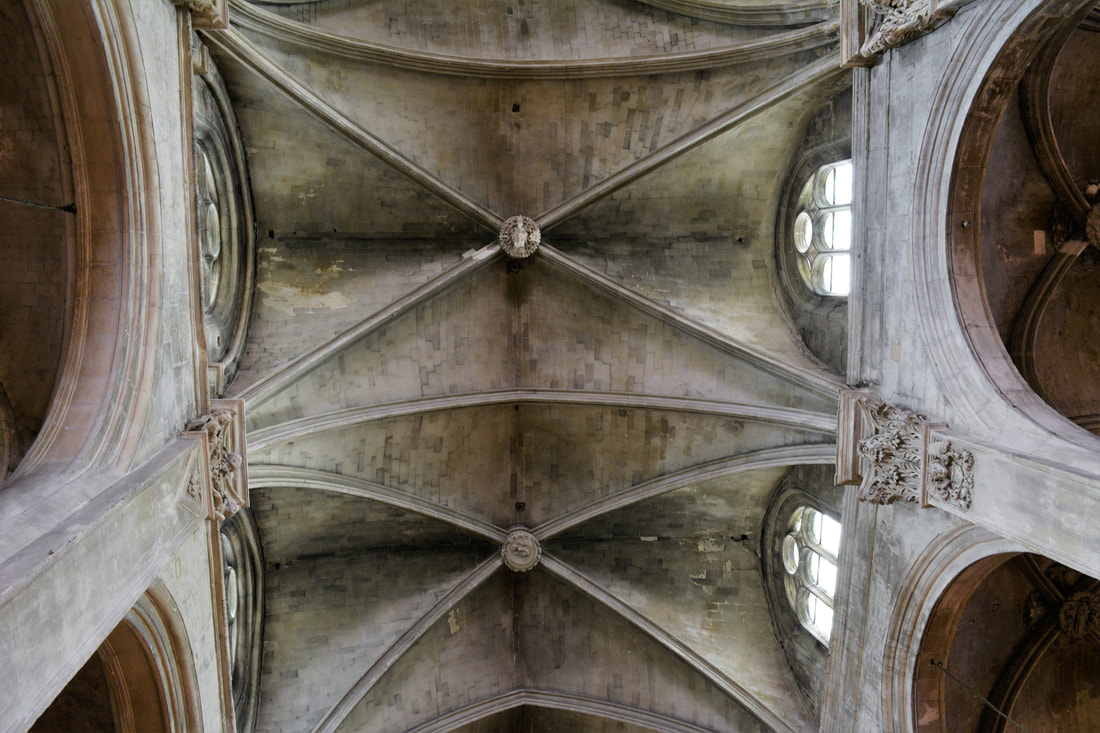

opus francigenum

once upon a time:

trying to imagine a Catholic western Europe

Le dernier maillon l'atteignit au-dessous du sein droit avec une telle force qu'il y fit voler un lambeau de chair comme un copeau sous la varlope. La surprise, plutôt que la souffrance même, lui arracha un cri aigu, vite étouffé, tandis qu'il levait encore la discipline de bronze. Le feu qui brûlait dans ses yeux n'était plus de ce monde. La heine aveugle qui l'animait contre lui-même était de celles que rien n'apaise ici-bas, et pour lesquelles tout le sang de la race humaine, s'il pouvait couler d'un seul coup, ne serait qu'une goutte d'eau sur un fer rouge....

Georges Bernanos, Sous le soleil de Satan

I must have been taught about this genre of literature in my youth, but it is the first time I actually try to read Georges Bernanos' Sous le soleil de Satan (1926). I have read Le Mystère Frontenac, a 1933 novel by François Mauriac. As far as I know, this is another example of the same genre of Catholic literature. Anyway, both books make a bizarre, and strangely obsolete reading today, as if the morality they pretended to discuss become something else. Well, in fact, the hypocrisy of the old moral formation is not exactly a novel discovery; Mauriac was already attacked in 1955 by the young Driss Chraïbi, the author of Les Boucs, that still makes a live, nervous, burning literature today. Contrary to the story of the old mistress of the papa Frontenac, a marginalized woman whose tragedy, apparently in the very focus of the novel, is somehow entirely missed, misconstrued, misused. As if the man were essentially right, justified in his choice of marginalising her. Excelling in his duty of protecting his family. Keeping his lower class mistress exactly in the place where she should remain.

This is how I approach the old Bernanos, trying to ask myself how western Europe might have once been Catholic, just like Poland is today, before something called secularisation happened. Or was that western Catholicism something different all the time? And this is why the secularisation never came to Poland, and will never come?

Apparently, Histoire de Mouchette, the opening section of Sous le soleil de Satan, treated as an extensive prologue, is quite something that people discuss in Poland right now. This violent, visceral, hysterical protest against becoming pregnant, that is not such a happiness and blessing as the Catholic dogma always wanted us to believe. Yes, this is something I do understand; it was worth being described and analysed in a book then as it is worth reading now, Mouchette, c'est moi. But all those obscure temptations of the priests that come later on, all that existential temptation of désespoir, all that perversion of cilice, both physical and mental one, this is something I never lived nor believed a human being may live, not in such a way as it is described and analysed in the book. This is why the novel is like a vivisection of an alien, and I do not find any useful truth in it.

Or perhaps... l'intolérable sensation d'être pris au piège... Does the priest prend au piège, full of monstrous anger and hatred just like in the quotation I put in the beginning, because he had been pris au piège? Is it, after all, a warning? A warning that brings about the secularisation, rather than a pious reading perpetuating the Catholicism? I am unable to read this book, to analyse it persuasively. Unless I should consider it as a psychopathological study.

L'abbé Donissan, the mentally unstable priest, after episodes of self-inflicted torture, also has nocturnal encounters with the devil; after such an encounter, he happens to talk to equally unstable Mouchette, causing her suicide. He carries the bleeding body of the young woman, her throat wide open, to the church. A pathetic scene that causes a consternation of ecclesiastical authorities. After five years of rest, he is sent to a parish again, where he tries to resurrect a dead child. Finally, the fame of the saint de Lumbres is such that it justifies a visit of Antoine Saint-Marin, de l'Académie Française, an ironic writer of a sort, the author of Cierge Pascal, that I privately associated with the figure of Anatole France. It is him who finds the priest dead, in a confessional. His mouth is still open, as if in a demoniac and grotesque exclamation, written all in capital letters:

-- TU VOULAIS MA PAIX, S'ÉCRIE LE SAINT, VIENS LA PRENDRE!...

And this is how the novel ends, leaving me even more puzzled.

Georges Bernanos, Sous le soilel de Satan, Paris, Plon, 1926.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 27.05.2021.

Georges Bernanos, Sous le soleil de Satan

I must have been taught about this genre of literature in my youth, but it is the first time I actually try to read Georges Bernanos' Sous le soleil de Satan (1926). I have read Le Mystère Frontenac, a 1933 novel by François Mauriac. As far as I know, this is another example of the same genre of Catholic literature. Anyway, both books make a bizarre, and strangely obsolete reading today, as if the morality they pretended to discuss become something else. Well, in fact, the hypocrisy of the old moral formation is not exactly a novel discovery; Mauriac was already attacked in 1955 by the young Driss Chraïbi, the author of Les Boucs, that still makes a live, nervous, burning literature today. Contrary to the story of the old mistress of the papa Frontenac, a marginalized woman whose tragedy, apparently in the very focus of the novel, is somehow entirely missed, misconstrued, misused. As if the man were essentially right, justified in his choice of marginalising her. Excelling in his duty of protecting his family. Keeping his lower class mistress exactly in the place where she should remain.

This is how I approach the old Bernanos, trying to ask myself how western Europe might have once been Catholic, just like Poland is today, before something called secularisation happened. Or was that western Catholicism something different all the time? And this is why the secularisation never came to Poland, and will never come?

Apparently, Histoire de Mouchette, the opening section of Sous le soleil de Satan, treated as an extensive prologue, is quite something that people discuss in Poland right now. This violent, visceral, hysterical protest against becoming pregnant, that is not such a happiness and blessing as the Catholic dogma always wanted us to believe. Yes, this is something I do understand; it was worth being described and analysed in a book then as it is worth reading now, Mouchette, c'est moi. But all those obscure temptations of the priests that come later on, all that existential temptation of désespoir, all that perversion of cilice, both physical and mental one, this is something I never lived nor believed a human being may live, not in such a way as it is described and analysed in the book. This is why the novel is like a vivisection of an alien, and I do not find any useful truth in it.

Or perhaps... l'intolérable sensation d'être pris au piège... Does the priest prend au piège, full of monstrous anger and hatred just like in the quotation I put in the beginning, because he had been pris au piège? Is it, after all, a warning? A warning that brings about the secularisation, rather than a pious reading perpetuating the Catholicism? I am unable to read this book, to analyse it persuasively. Unless I should consider it as a psychopathological study.

L'abbé Donissan, the mentally unstable priest, after episodes of self-inflicted torture, also has nocturnal encounters with the devil; after such an encounter, he happens to talk to equally unstable Mouchette, causing her suicide. He carries the bleeding body of the young woman, her throat wide open, to the church. A pathetic scene that causes a consternation of ecclesiastical authorities. After five years of rest, he is sent to a parish again, where he tries to resurrect a dead child. Finally, the fame of the saint de Lumbres is such that it justifies a visit of Antoine Saint-Marin, de l'Académie Française, an ironic writer of a sort, the author of Cierge Pascal, that I privately associated with the figure of Anatole France. It is him who finds the priest dead, in a confessional. His mouth is still open, as if in a demoniac and grotesque exclamation, written all in capital letters:

-- TU VOULAIS MA PAIX, S'ÉCRIE LE SAINT, VIENS LA PRENDRE!...

And this is how the novel ends, leaving me even more puzzled.

Georges Bernanos, Sous le soilel de Satan, Paris, Plon, 1926.

Neuville-sur-Oise, 27.05.2021.

Loire Valley

Le Clos Lucé

The Clos Lucé is a mansion in Amboise where Leonardo da Vinci spent the last decade of his life. Such a peripheral museum could not bring forth the original paintings of the Renaissance master, of course, so the exposition is limited to some rather cursory attempts at reconstructing the interiors in which Leonardo might have lived and presenting some models of his famous machines. The garden, on the contrary, contains quite an original idea: that of recreating, through some vapor producing installations, the sfumato of Leonardo's paintings.