what is Turkish literature?

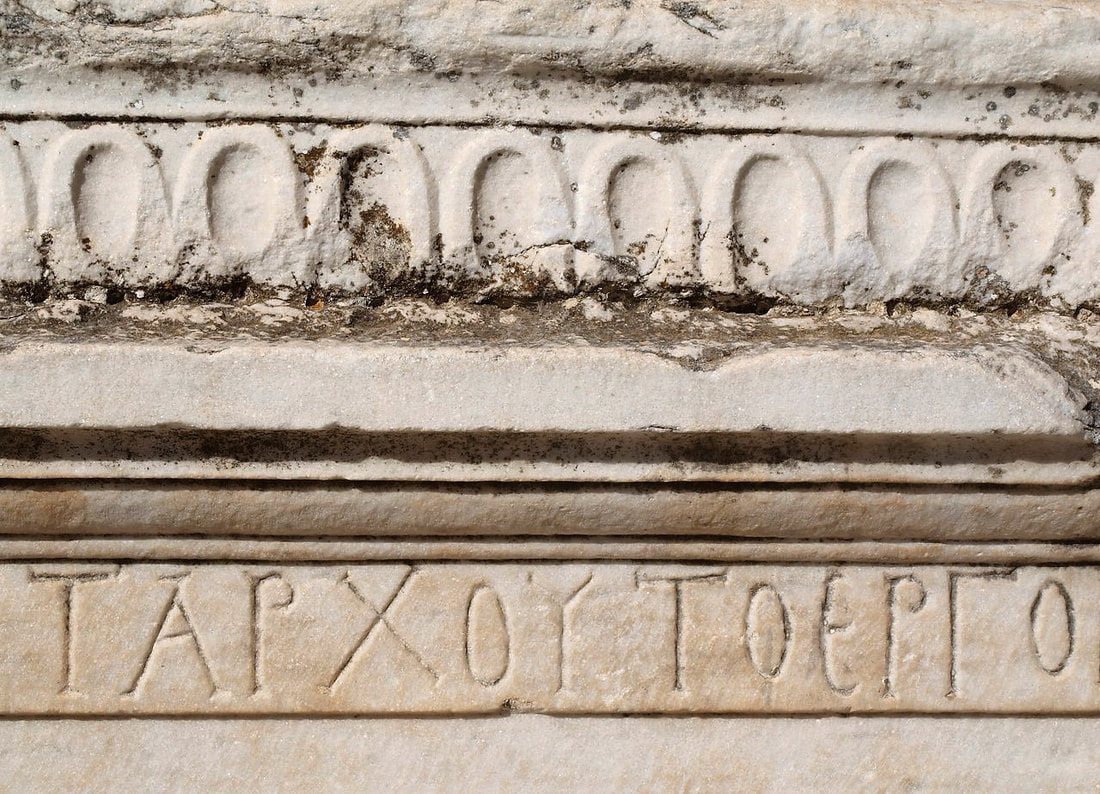

The first problem connected to Turkish literature is where to begin. Some people say that it spans over more than a millennium, and treat Turkic oral epics of Central Asia as its roots. In this broad sense, such oral texts as, just to give an example, the Epos of Manas (belonging rather to Kyrgyz people) would be included in an encompassing definition of Turkish literature, giving an expression to pre-Islamic, nomadic, shamanistic way of life.

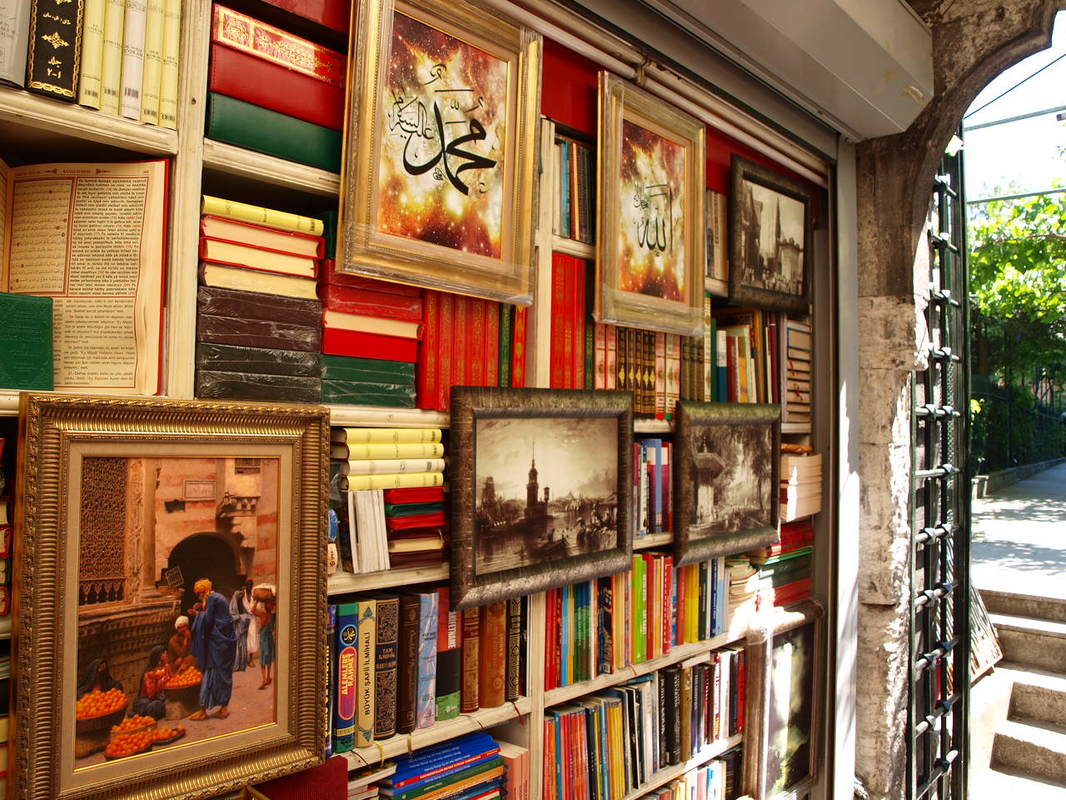

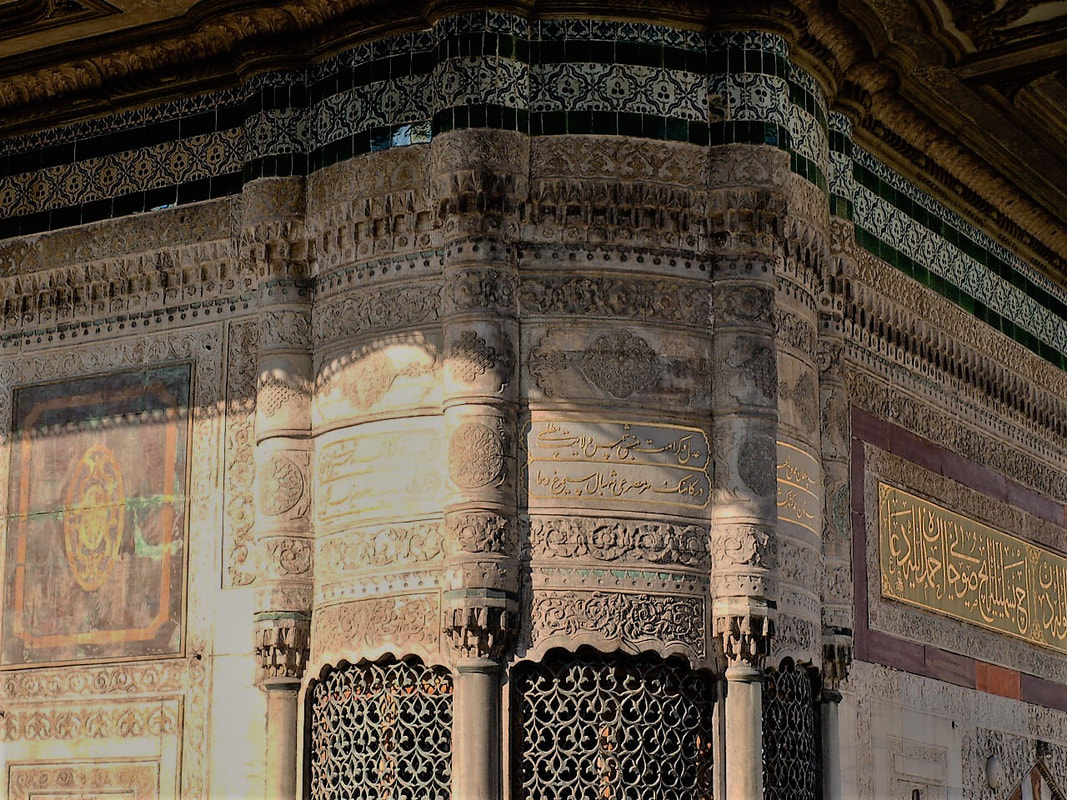

Another way of facing the problem is to start the history of Turkish literature with the Seljuk conquest of Anatolia (late 11th c.). This is when a written, rather than oral, literary tradition is born, in an intimate connection with Persian and Arab letters, and of course with Islam. This would be the line in which the place of an early poet would be occupied by such a figure as the 13th-c. Sufi Yunus Emre. Its heyday would begin in the 15th century, with various poets, but also with such a unique work as the 10-volume Book of Travels of Evliya Çelebi (1611-1682). All along those centuries of the Ottoman Golden Age (15th to 18th c.), there is a clear distinction between noble genres and folk traditions, the latter encompassing such elements as the famous adventures of Nasreddin Hoca and the shadow theatre.

Finally, the 19th to 21st centuries are treated as a modern period, in many ways opposed to former traditions, essentially through various trends and aspects of westernisation. After the 19th-c. reforms of the Tanzimat, the 20th century brings about a proliferation of currents, such as New Literature, The Dawn of the Future, National Literature movement, and so on. And this is how we arrive at the contemporary Turkish novel that starts more or less in the 1960s and culminates with Orhan Pamuk that everyone knows. This is of course the rough Eurocentric vision that privileges prose and ignores poetry, which still makes the greater part of Turkish literature, hardly visible from the perspective of the international book market.

Another way of facing the problem is to start the history of Turkish literature with the Seljuk conquest of Anatolia (late 11th c.). This is when a written, rather than oral, literary tradition is born, in an intimate connection with Persian and Arab letters, and of course with Islam. This would be the line in which the place of an early poet would be occupied by such a figure as the 13th-c. Sufi Yunus Emre. Its heyday would begin in the 15th century, with various poets, but also with such a unique work as the 10-volume Book of Travels of Evliya Çelebi (1611-1682). All along those centuries of the Ottoman Golden Age (15th to 18th c.), there is a clear distinction between noble genres and folk traditions, the latter encompassing such elements as the famous adventures of Nasreddin Hoca and the shadow theatre.

Finally, the 19th to 21st centuries are treated as a modern period, in many ways opposed to former traditions, essentially through various trends and aspects of westernisation. After the 19th-c. reforms of the Tanzimat, the 20th century brings about a proliferation of currents, such as New Literature, The Dawn of the Future, National Literature movement, and so on. And this is how we arrive at the contemporary Turkish novel that starts more or less in the 1960s and culminates with Orhan Pamuk that everyone knows. This is of course the rough Eurocentric vision that privileges prose and ignores poetry, which still makes the greater part of Turkish literature, hardly visible from the perspective of the international book market.

I have readOrhan Pamuk, Beyaz Kale / The White Castle (1985), Benim Adım Kırmızı / My Name is Red (1998), Kar / Snow (2002)

|

Vertical Divider

|

I have written... nothing ...

|

|

Vertical Divider

|

Gazali'nin aynası

It is a beautiful, tender language that charms me, and that I once intended to learn (yes, also this one). Connected to the horizon of my speech through some threads of Arabic made invisible by deliberate reforms a few decades ago.

I've read Orhan Pamuk just like everyone else. I have perhaps a dozen of Turkish novels in Polish and English versions in my Multilingual Library; some of them brought from Turkey as souvenirs. But what I've heard in Leiden is that Turkish novels are not half as good as Turkish poetry. I can easily believe this. No book, on the other hand, can render the sound of it, unless one day I learn how to read it aloud for myself. Phonetically, the language makes impression of fluidity; it sounds natural and easy to speak. At the same time, it makes an impression of rich texture, with its inaudible ğ's and aspired T's; sounds tender with its ç's and c's. Makes a great choice of consonants, none of them alien or unpronounceable to me. And I'm really not sure if this verse applies to me: For the roads of the East that are not oriental there are no passages in the West, with its confusion of parts: the History atlas, emblems of the soul, inaccurate scales, broken compass, blind lighthouse, difference in mentality points of view, chain of continuity, units of currency, kinds of measuring, wounded consciousness, eclipse of reason, Plato's cave, Gazali's mirror, an empire of signs and images Even if I'm not really sure what a Gazali's mirror might be. Did he mean that little Fürstenspiegel that al-Ghazali wrote for some unknown Seljuq prince? Turkish Literature Night, Universiteit Leiden, 30.04.2019 |