what is Andalusian literature?

Al-Andalus, the western part of Islamic world, had a cultural and intellectual peculiarity. It is also possible, as I believe, to speak about peculiar Andalusian literature, with its own, characteristic genres, added to the classical Arab literature, its choice of predilect topics, its tone, its spirit of liberty. As a political entity, al-Andalus ceased to exist after the conquest of Granada by the Catholic Kings. But the spirit, just at that of the Cathar country, is something that survives and inspires.

I have readIbn Hazm, Tawq al-Hamama

|

Vertical Divider

|

I have writtenAl-Andalus: transkulturowa przestrzeń pamięci

|

Cordoba

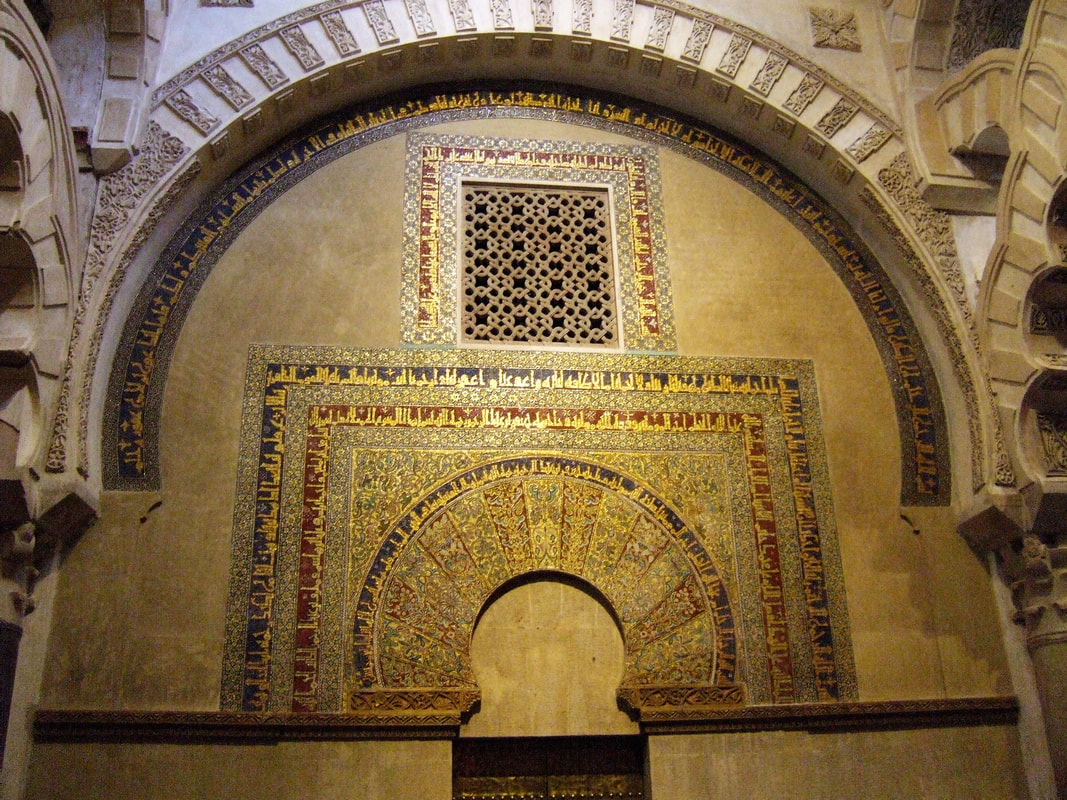

"The Islamic hall of prayer, unlike a church or a temple, has no centre towards which worship is directed. The grouping of the faithful around a centre, so characteristic of Christian communities, can only be witnessed in Islam at the time of the pilgrimage to Mecca, in the collective prayer around the Kaaba. In every other place believers turn in their prayers towards that distant centre, external to the walls of the mosque. But the Kaaba itself does not represent a sacramental centre comparable to the Christian altar, nor does it contain any symbol which could be an immediate support to worship, for it is empty. Its emptiness reveals an essential feature of the spiritual attitude of Islam: whereas Christian piety is eager to concentrate on a concrete centre -- since the "Incarnate Word" is a centre, both in space and in time, and since the Eucharistic sacrament is no less a centre -- a Muslim's awareness of the Divine Presence is based on a feeling of limitlessness; he rejects all objectivation of the Divine, except that which presents itself to him in the form of limitless space."

Titus Burckhardt, "The foundations of Islamic art", in: Sacred Art in East and West. Its Principles and Methods, trans. by Lord Northbourne, London: Perennial Books, 1967, p. 106.

Titus Burckhardt, "The foundations of Islamic art", in: Sacred Art in East and West. Its Principles and Methods, trans. by Lord Northbourne, London: Perennial Books, 1967, p. 106.

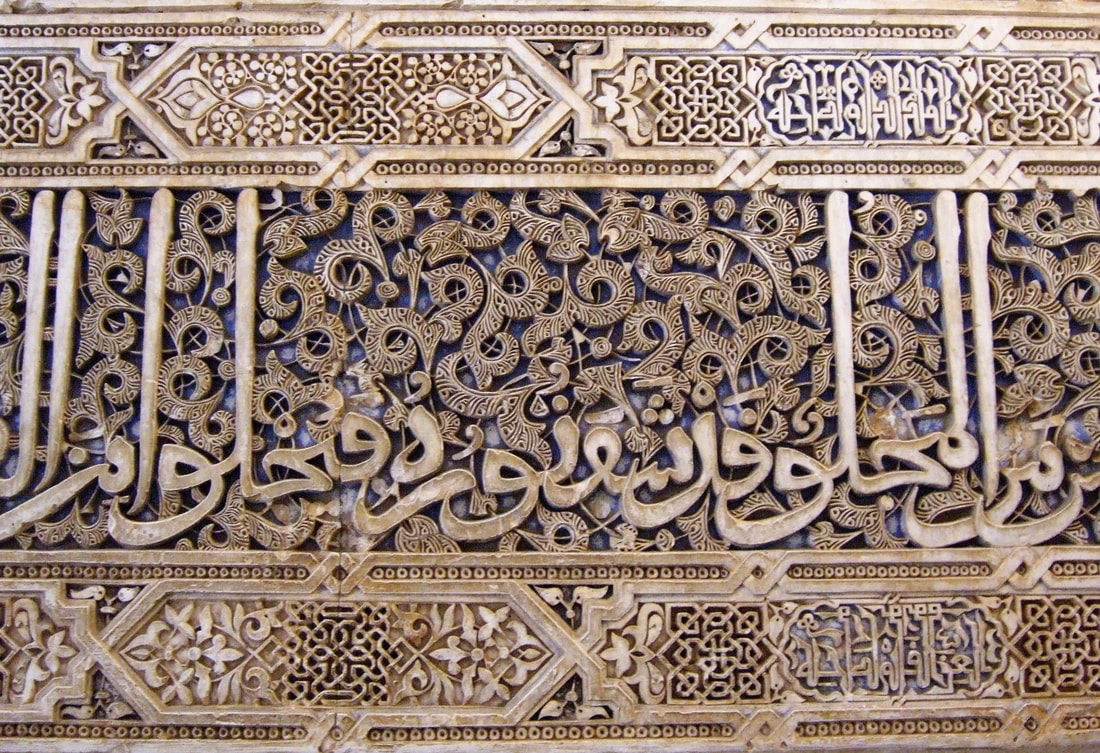

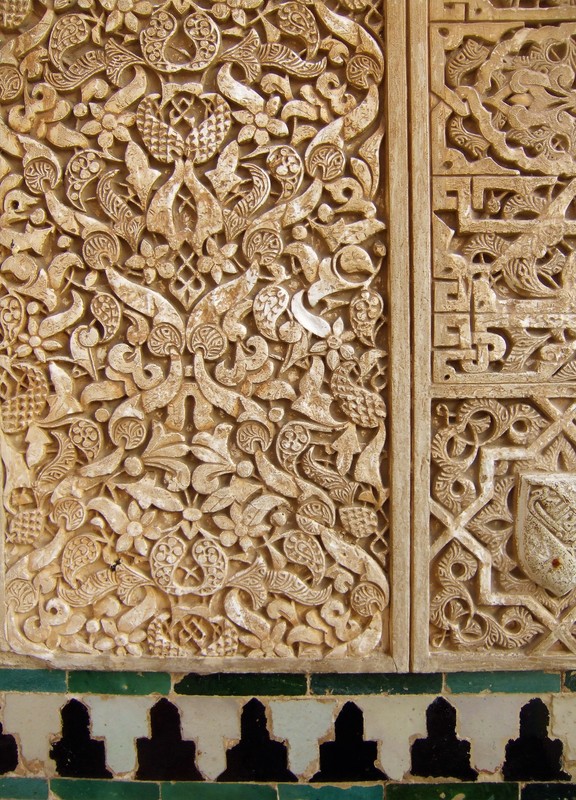

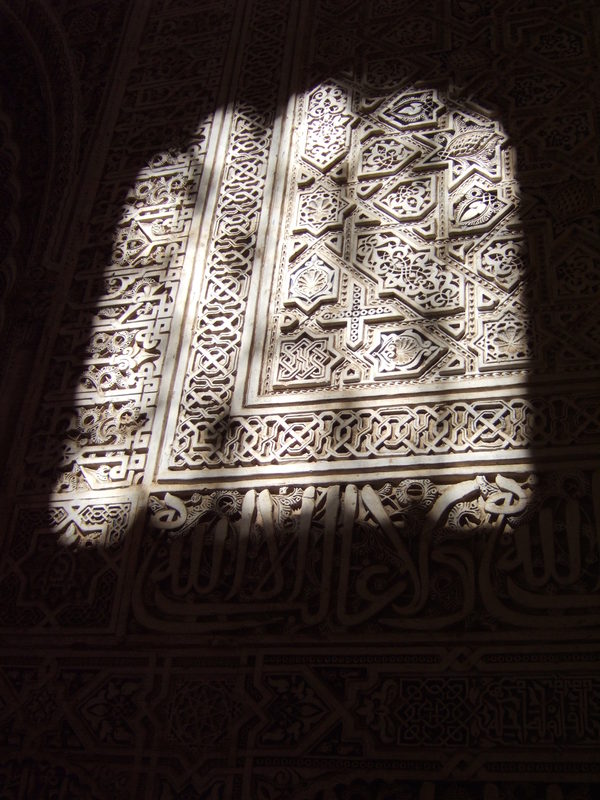

"At the risk of pressing the point too hard, let it be said that for a Muslim the arabesque is not merely a possibility of producing art without making images; it is a direct means for dissolving images or what corresponds to them in the mental order, in the same way as the rhythmical repetition of certain Koranic formulae dissolves the fixation of the mind on an object of desire. In the arabesque all suggestion of an individual form is eliminated by the indefinity of a continuous weave. The repetition of identical motives, the flamboyant movement of lines and the decorative equivalence of forms in relief or incised, and so inversely analogous, all contribute to this effect. Thus at the sight of glittering weaves or of leafage trembling in the brease, the soul detaches itself from an internal objects, from the "idols" of passion, and plunges, vibrant within itself, into a pure state of being."

Titus Burckhardt, "The foundations of Islamic art", ibidem, p. 111.

Titus Burckhardt, "The foundations of Islamic art", ibidem, p. 111.

"The walls of certain mosques, covered with glazed earthenware mosaic or a tissue of delicate arabesques in stucco, recall the symbolism of the curtain (hijāb). According to a saying of the Prophet, God hides himself behind seventy thousand curtains of light and darkness; "if they were taken away, all that His sight reaches would be consumed by the lightnings of His Countenance". The curtains are made of light in that they hide the Divine "obscurity", and of darkness in that they veil the Divine Light."

Titus Burckhardt, "The foundations of Islamic art", ibidem, p. 111.

Titus Burckhardt, "The foundations of Islamic art", ibidem, p. 111.